Before the coronavirus pandemic, Maria Ayala would drop her 5-year-old son, Darwin, off at his babysitter’s house early in the morning. Then, she’d drive to the University of Maryland, where she works as a housekeeper.

Now, her regular shift — 7:30 a.m. to 4 p.m. — overlaps with her son’s online classes. She can’t leave him alone during his class, which starts at 7:45 a.m. and ends at 1:55 p.m. And although she’s pleaded with her managers to change her schedule to work nights, there are no more spots available during evening hours.

So, Ayala hasn’t worked a full shift since Darwin’s classes started on Aug. 31. Her manager has assured her that she won’t lose her job if she needs to stay home to take care of Darwin. But since she’s not guaranteed to be paid either, that’s not necessarily reassuring.

“We’re going to have a job, okay. When all of this is over, we’ll be able to go back to work,” she said. “But until then, how are we going to eat?”

For many parents at this university, the upcoming school year will bring unique sacrifices and challenges. While some are weighing the hazards of sending their children back to day care against the costs of keeping them at home, others are worried about their academic and professional futures, as well as the financial consequences that could accompany the sudden loss of help with child care.

And they’re not alone in their anxiety. Surveys have found that parents across the country are struggling to balance caring for their children with the hardships brought about by the pandemic. A study conducted by a caregivers networking site found that of 1,000 parents surveyed, 73 percent had to make “major changes at work” to meet their children’s needs. As the primary caregivers in the majority of families, women are disproportionately facing the brunt of this new burden. Of the women who reported becoming unemployed during the pandemic, one in four said it was because of a lack of child care, The Washington Post reported. That’s twice the rate among men, according to The Post.

Ayala knows there are women everywhere right now in situations just like hers. But with the way things are going, she feels like she’ll inevitably become one of those forced to leave their jobs to care for their children.

“What other option do we have?” she asked.

***

Amanda Hoffman-Hall’s house was unusually quiet.

For months, as she worked by the window of a spare room, she could hear her two children playing in the living room. But the house was now empty of their chatter — at least for a little while. They were back at day care.

Since Aug. 17 — when her kids returned to day care — Hoffman-Hall’s routine has been similar to what it was pre-pandemic. She drops them off in the morning at 8 a.m. and picks them up at 3:30 p.m. Yet, as the school year starts for her and her kids, the apprehension still lingers. She doesn’t know what she would do if her children contracted COVID-19.

“It’s gonna be chaos,” said Hoffman-Hall, a lecturer and the director of undergraduate studies in the geographical sciences department.

In the same week this university closed due to the coronavirus pandemic, the day care that her kids — 4-year-old Chip and 1-year-old Posy — attended shut down, Hoffman-Hall said.

At first, it was virtually impossible to get anything done, Hoffman-Hall said. Back then, her husband, an essential worker in charge of a FedEx branch, was constantly on the job: He worked 75 days in a row, including weekends, from early morning through the afternoon. So, Hoffman-Hall had to take care of Chip and Posy, all while she worked on her dissertation.

The only times she felt productive was after she put them to bed, when she would work until 2 a.m. But her sleep was rarely undisturbed — her baby daughter would sometimes wake up at 3 a.m., and, by 6 a.m., the day would start again. During those times, Hoffman-Hall felt like the lines between her family life and workday were blurred, usually at the expense of her physical health.

While preparing to defend her dissertation in May, she found it hard to synthesize information, she said. She would find herself eating jelly beans for the sake of having something quick and easy to eat, and she drank coffee nonstop.

Things got better when she and her husband hired a nanny, who came to their house to watch the children during the day. But the hiring process was strange. They had to ask applicants whether they were abiding by social distancing rules and how many people they saw on a regular basis. And with Hoffman-Hall’s husband still working, they needed to make sure the nanny would be comfortable working for them, with the risk of contracting COVID-19.

“It’s definitely a level of trust that goes beyond a typical nanny-parent relationship,” she said.

She considered hiring a nanny for her kids’ school year as well. But she would have to either find another full-time nanny, as the one she had hired would be going back to college, or keep her and find another part-time nanny. But she didn’t feel comfortable having two different people coming in and out of their house, Hoffman-Hall said.

Despite initially being reluctant to send her children back to day care, it ultimately felt like the best option for their family, she said. Her oldest son was just getting to the age where he had close friends. He was adapting as much as he could, but he would ask his mother all the time when he would be able to go to school again, Hoffman-Hall said.

“It was becoming detrimental to my kids that I wasn’t able to have them interact with other people,” Hoffman-Hall said.

When Hoffman-Hall and her husband decided they would be sending their children to day care again, they started looking for a center that was licensed to care for the children of essential workers, meaning it would be allowed to stay open, even if the state’s economy shut down once again.

Now, every morning, Hoffman-Hall drops her children off at the center in Prince George’s County. She walks them to the door with other parents, all wearing masks, and the staff take the kids’ temperatures.

In normal times, if Hoffman-Hall were enrolling her children at a new day care center, she would be able to take a tour of the building and meet the teachers. But now, she has no idea what her children’s classroom looks like. The only clues she gets come from photos sent by the center. In some of them, her 4-year-old is wearing a mask.

If the day care does close, which could happen in the event of a second wave, or one of her children gets sick, Hoffman-Hall has no backup plan. This semester, she will teach two days a week, thankfully during her daughter’s usual naptime. But the anxiety lingers.

“I’m really not sure what we’re going to do.”

***

In March, the school where Erica Merson’s daughter was attending kindergarten moved online. Keeping her daughter, Andie, focused on virtual learning was challenging for Merson, a staff member at this university. Her teachers were sharing short videos and worksheets, but the classwork wasn’t engaging, Merson said. And she didn’t have the resources or skills to make it more captivating, either.

Six-year-old Andie is now in first grade, and though Washington, D.C., public schools will be online until at least Nov. 6, Merson and other neighborhood parents have decided to “pod up” and hire a tutor together that their children will share.

Merson thinks Andie has noticed the loss of normalcy, and she’s worried her daughter feels like her life has been taken away. Though she found ways to entertain Andie over the summer, with nature walks and art projects, she’s concerned about what it will be like as the weather grows colder, and opportunities to go outside decrease. It’s stressful to think the days will be even more restrictive, she said.

“It’s so hard because you’re trying to manage all your own feelings and fears and anxieties,” said Merson. “While also trying to keep their world and their lives and their experiences as normal as possible.”

Some days have been better, like the day Andie learned how to ride her white and pink bicycle. She had seen her friends hit that milestone, but she was sometimes afraid to abandon her training wheels.

“We would practice a little bit, and she would get a little braver,” she said. “One day, it clicked.”

Now, as the school year starts, Merson feels hopeful about the pod system. But it also brings new concerns and anxieties — the upcoming semester will be completely different, she said.

While the increased potential for exposure to the virus is an obvious concern, Merson also worries about how the virtual classes from Andie’s public school and the in-person tutoring will mesh.

“My hope is that they will be facilitative of each other, not obstructive,” she said.

And at some point, Merson will have to host the pod at her house, at the same time she works remotely. Ideally, the tutor will be able to manage the children by themselves, but Merton doesn’t know if that will be the reality. She hopes she won’t have to be an educator, a mom and an employee all at the same time like she was in the spring.

“My hope is that my role as the primary educator hopefully will not be what it was in the spring,” she said.

***

The preschool 4-year-old Abigail Mullan attends is set to reopen in less than two weeks, but her parents are still on the fence about sending her back.

After months of online education and quarantine, Erin Janulis — a doctoral student in the education college — says her daughter can’t wait to return to school. She misses her friends, and seeing them over Zoom just isn’t the same. She’s not yet at the age where she can hold extended conversations, Janulis explained.

They’re quickly running out of things to do at home, too. Nature walks, scavenger hunts around the house and art projects aren’t as exciting as they once were.

“We did that yesterday,” she says to her mother.

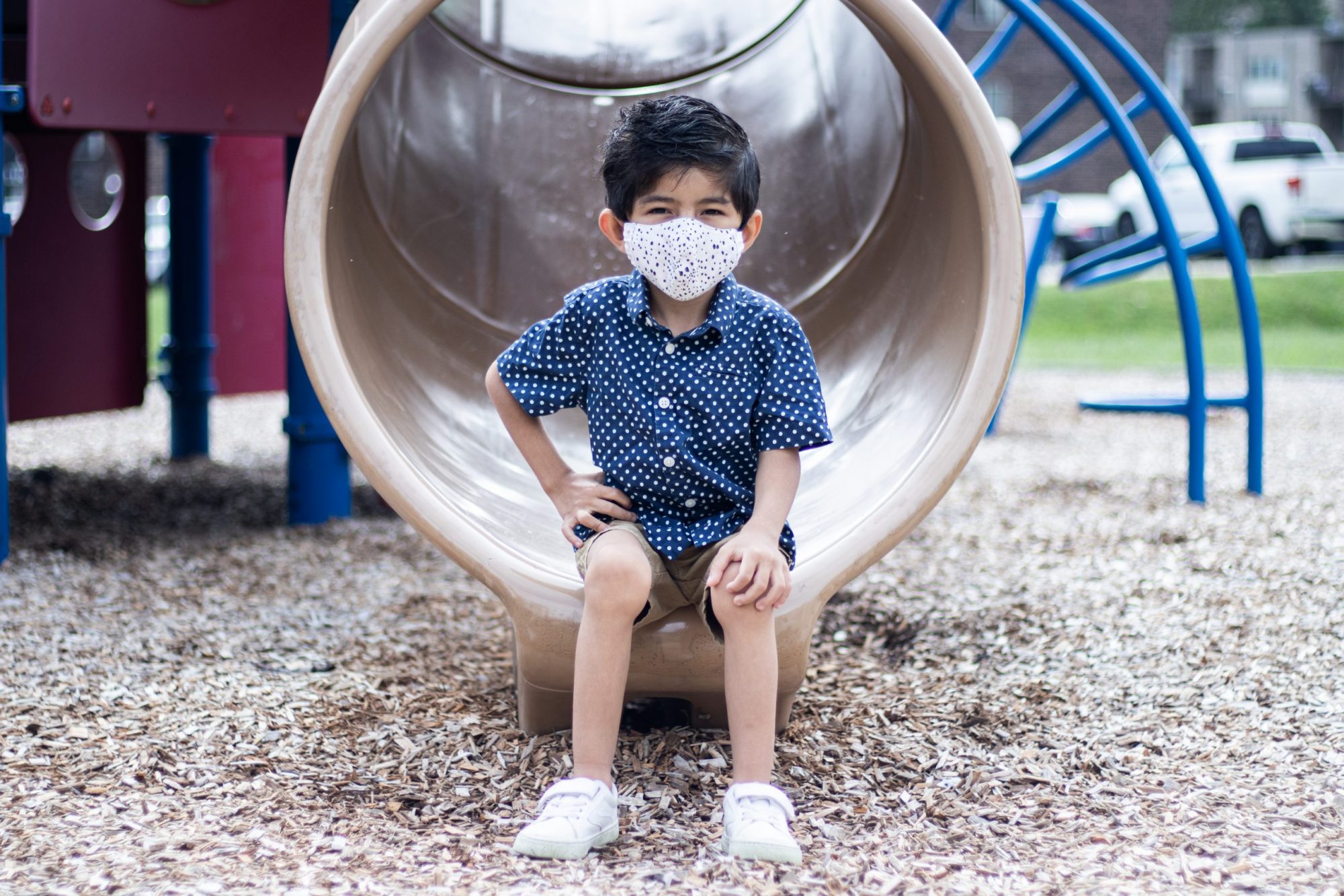

It’s also true that the Center for Young Children, the preschool under this university’s education college that Abigail attends, is taking steps to prevent a coronavirus outbreak. Class sizes will be limited, and masks will be mandatory for faculty members and strongly encouraged for children. Student lunches will also be required to be packed in disposable containers, rather than the reusable containers that were once recommended.

And yet, Janulis says, there is still risk of exposure. She and her husband are planning to wait until the week of Sept. 14, when the center opens, to decide whether to send Abigail back.

“Which is not the best way to make informed decisions,” she said. “It pains me to say that.”

In the meantime, the family is going through all the steps they’d have to if Abigail were to return to school. They’re searching for a place to get her tested for COVID-19, for instance, which is proving tricky. There aren’t that many testing sites for children Abigail’s age, Janulis said.

Janulis and her husband are also tempering Abigail’s expectations for school, preparing her to return to a familiar environment that will suddenly be infiltrated by unfamiliar rules. Some things will have to change at home, too. Abigail might not be able to take her backpack to the center, but rather a duffel bag or a tote bag, something that is easier to clean.

And as Janulis and her husband weigh their options, Janulis is facing down another challenge: writing her dissertation.

After six years in graduate school, Janulis hoped to be at the proposal stage of her project by now. Now, she doesn’t see that happening until December at the earliest.

“And that’s probably being ambitious, given how much progress I’m making these days,” she said.

The uncertainty that comes with the pandemic has made it even more difficult for Janulis to predict a reasonable timeline for finishing her dissertation, she said. And its dragging progress means she is taking time away from her family, from her career — and adding semesters she’ll have to pay tuition for.

Janulis has considered taking a semester off and working on her dissertation independently. But she isn’t entirely sure that would benefit her. If she does take leave, she’s not supposed to be in contact with any of her advisers.

For now, Janulis works at an office in her house while a nanny takes care of Abigail and her son Evan, who is almost 2 years old. Whenever she does leave the room, she said, her children often run to her, screaming “Mommy!”

While it can be a welcome distraction, it also makes it harder to focus on work.

“I need some motivation to move forward,” she said.

***

Though Ayala’s husband also works, serving as a technician at a dialysis center from 5 a.m. to 8 p.m., his salary alone can’t cover all of their expenses. The money he brings in is mostly used for rent and the electricity bill. Ayala’s salary pays the other bills and puts the food on the table.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen to us,” Ayala said.

Throughout the pandemic, Ayala hasn’t left Darwin with his usual babysitter. The babysitter took care of other children, she said, and Ayala, who has asthma, did not want to risk being exposed to the virus.

Her medical condition is another reason she can’t afford to stop working. If she stays home and doesn’t work, she’d no longer be able to afford her health insurance. The money she gets from the university, however little, is necessary, she said.

Ayala recently found out that she would be one of the housekeepers cleaning rooms where students who tested positive for COVID-19 will be in isolation. Even though students are not supposed to leave their rooms as she and her coworkers clean, she is still worried, she said.

“Even doctors get the virus,” she said. “Who is going to guarantee we will not, if we are not doctors?”

The past few months have been sad and frustrating, Ayala said.

“But [G]od will provide me and everybody who’s in need.”

This story has been updated.