By Eric Harkleroad, Joe Ryan and Julia Nikhinson

Senior staff photographers

On May 25, a video captured George Floyd’s last moments alive — his calls for his mother and rasping cries that he couldn’t breathe as a white Minneapolis police officer dug his knee into his neck. The very next day, hundreds poured into the city’s streets to demand justice in the wake of his killing.

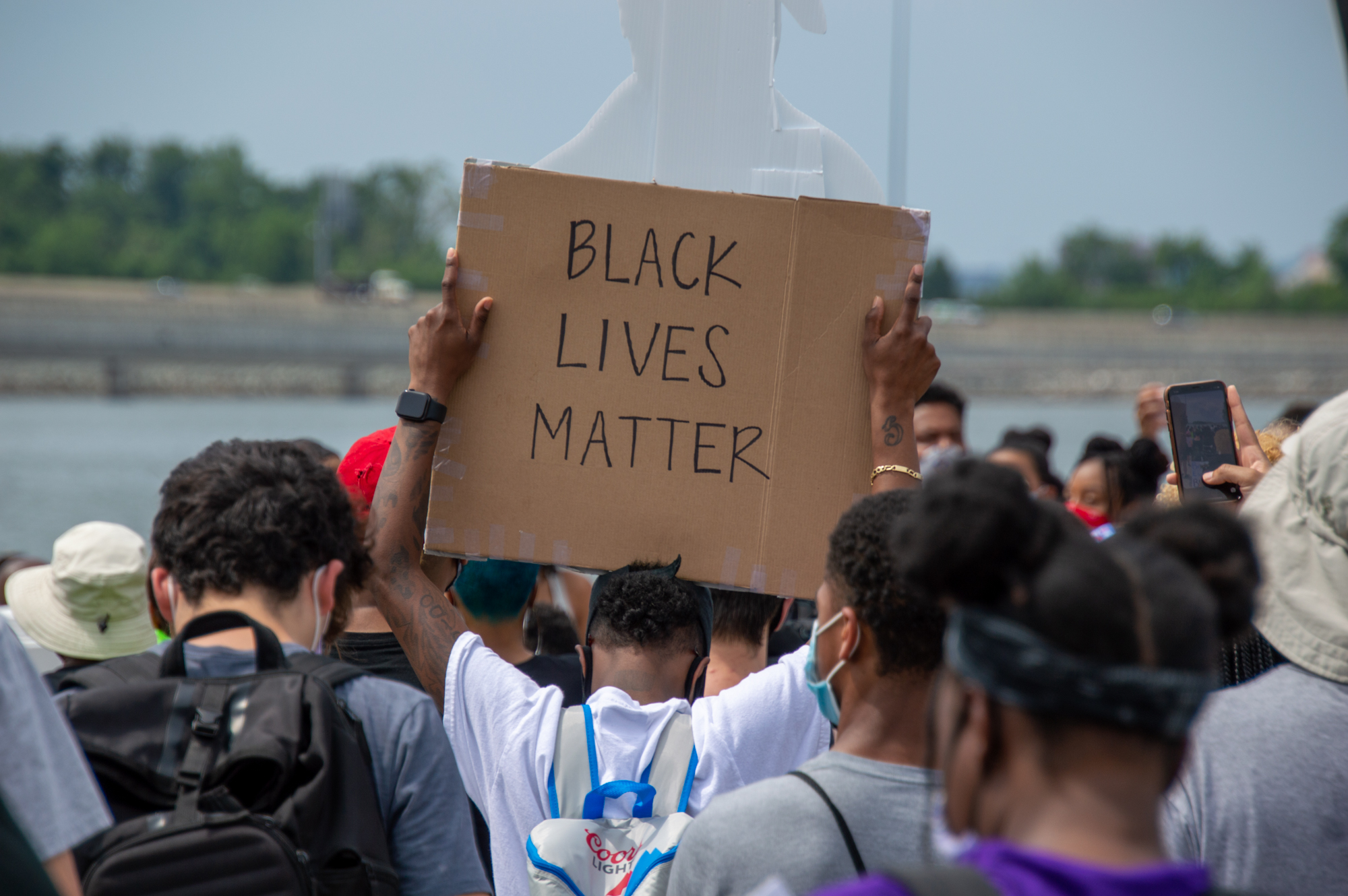

Since then, the protests have only accelerated. In at least 700 cities and towns, demonstrators have gathered to protest against police brutality and systemic racism.

Prince George’s County is no exception, with multiple protests cropping up across the county this weekend. Here’s what some of those protests looked like, through the lenses of three Diamondback photographers.

Saturday, June 6

NATIONAL HARBOR — Hundreds gathered at the National Harbor to march in protest of systemic racism and police brutality, calling for justice for George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and other victims of police violence. The protest, which began near the carousel at National Harbor, crossed the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge into Alexandria, Virginia.

Protesters spent the first hour of the demonstration listening to speeches, musical performances and prayers.

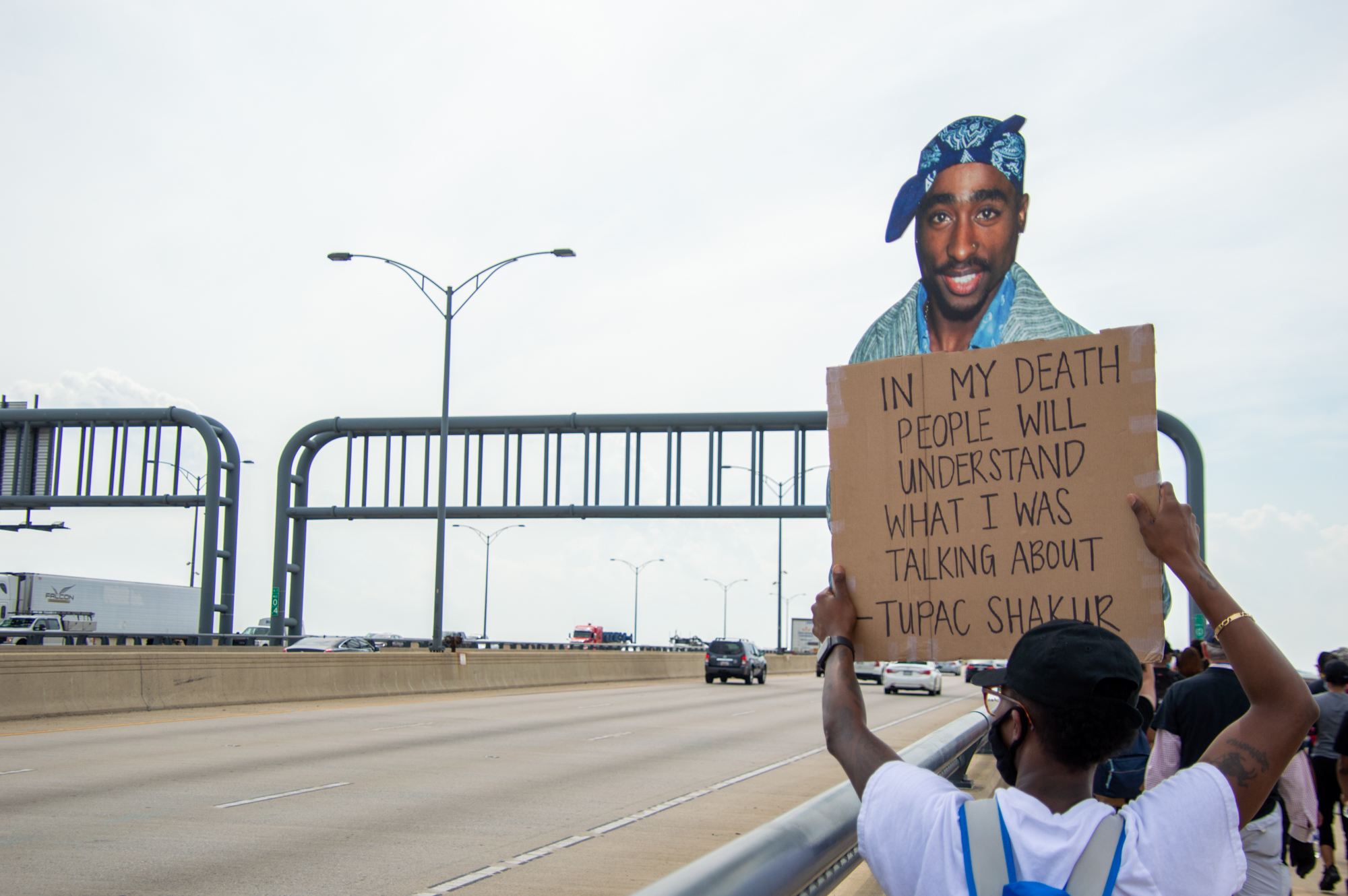

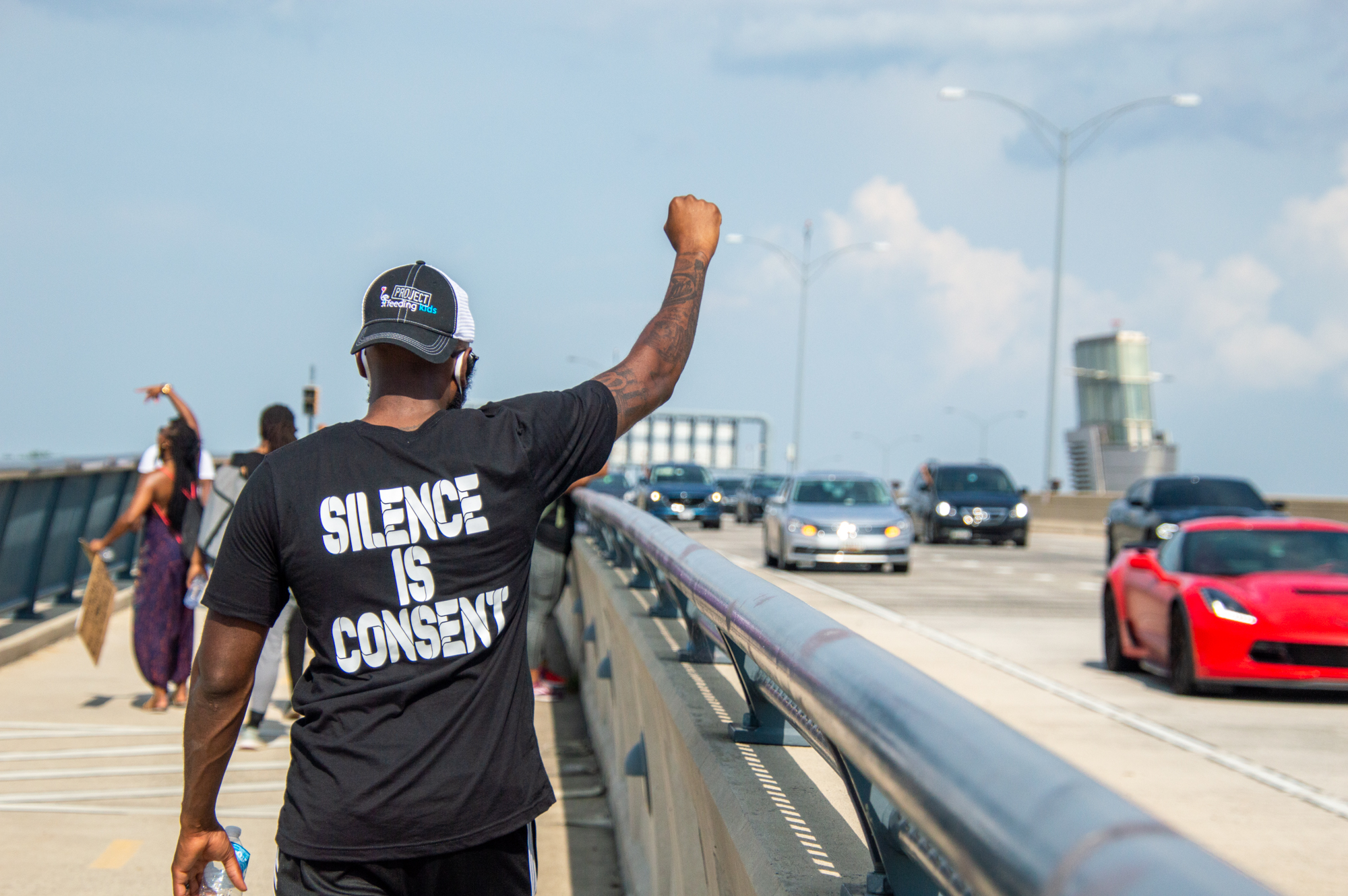

They then crossed the bridge’s pedestrian path, with some passing drivers showing their support by honking their horns and raising closed fists out of car windows.

The Woodrow Wilson Memorial Bridge is more than a mile long, with almost no shade — something that was especially noticeable on Saturday, as temperatures reached the high 80s.

But even a long walk in the heat couldn’t wilt protesters like Lawrence Taylor, a county pastor who led the crowd in chants. Cries of “Hands up, don’t shoot,” “We want peace, not racist-ass police” and “Your life matters” echoed across the bridge.

The protest remained peaceful throughout the afternoon, even receiving support from local police as county police chief Hank Stawinski gave a speech denouncing police brutality.

The march ended beneath a bronze sculpture in Alexandria’s Contrabands and Freedmen Cemetery, where hundreds of freedom-seeking African Americans who fled to the city are buried. The statue, called “The Path of Thorns and Roses” commemorates the lives of the refugees who died as they attempted to escape slavery in the South.

Sunday, June 7

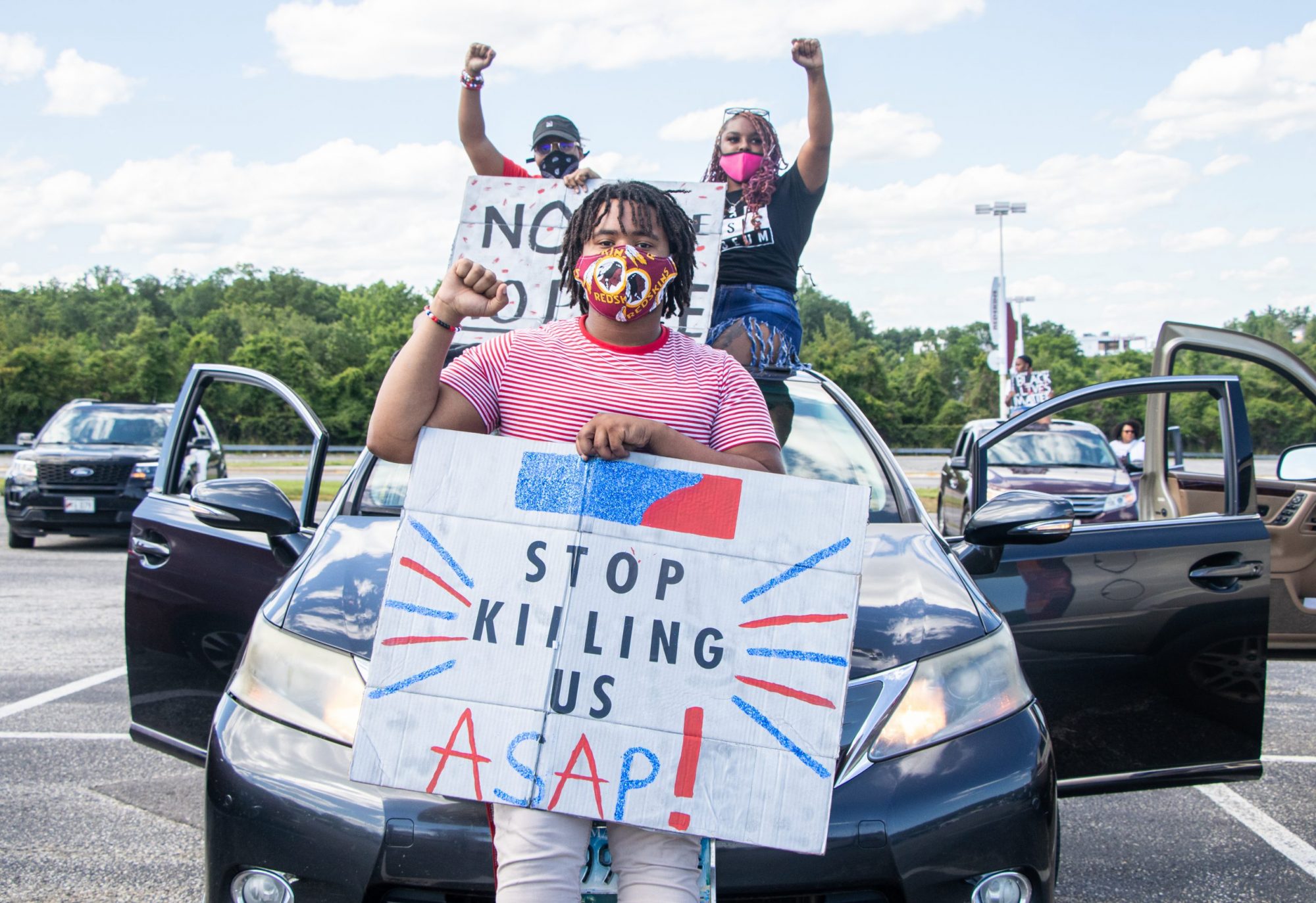

LANDOVER — As cars filled the parking lot of FedExField stadium, organizers passed out water bottles and chalk markers to a crowd of dozens of demonstrators.

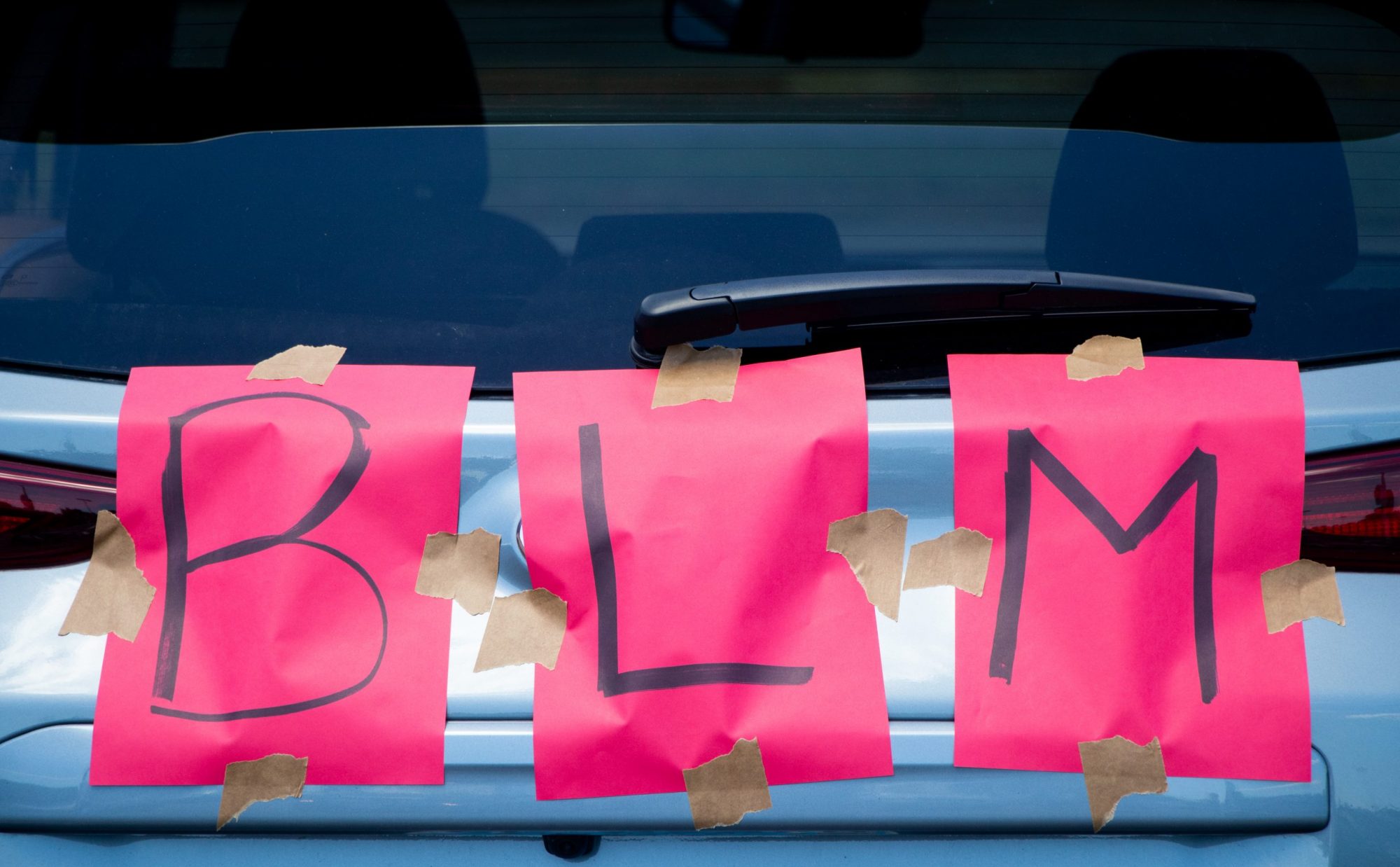

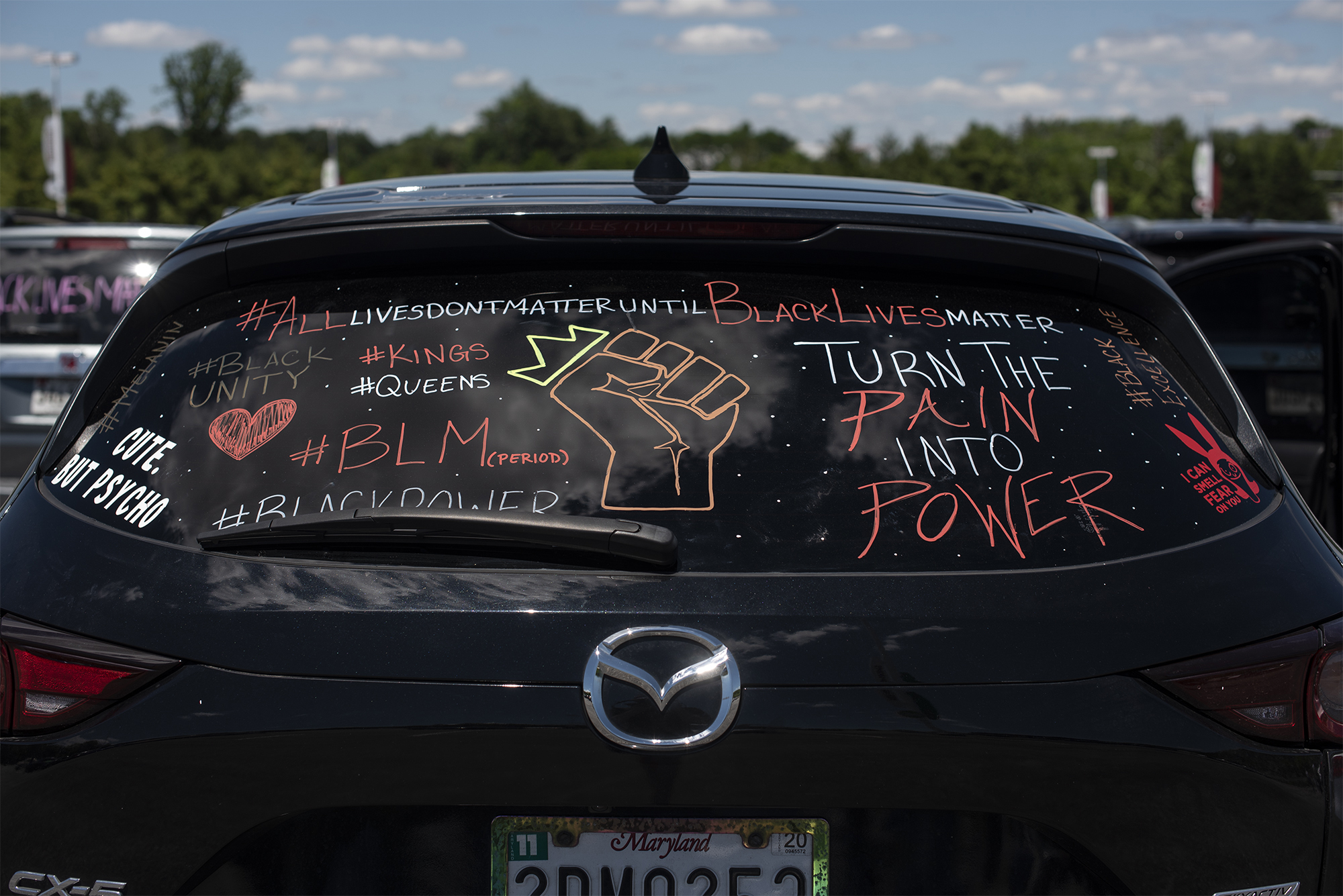

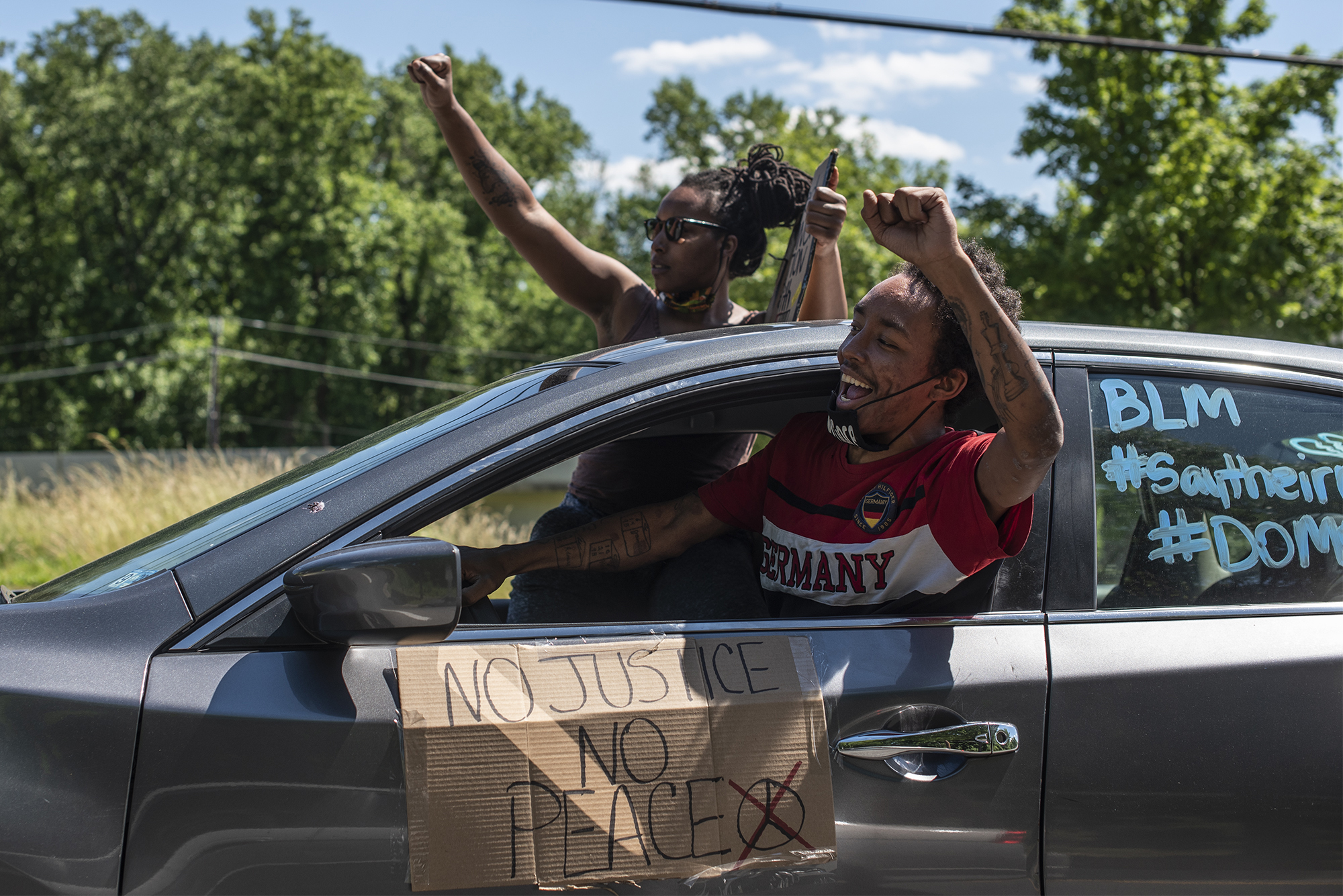

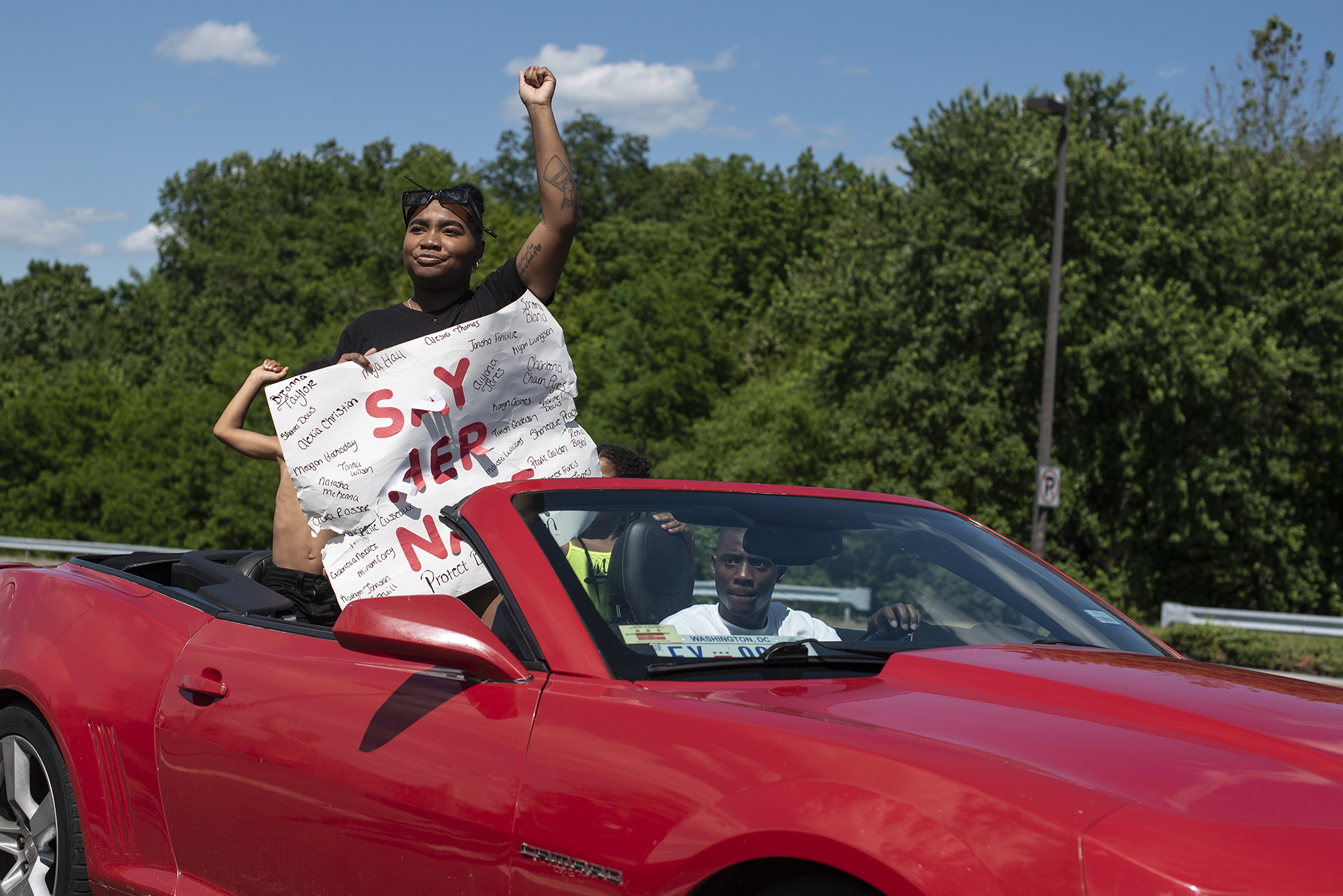

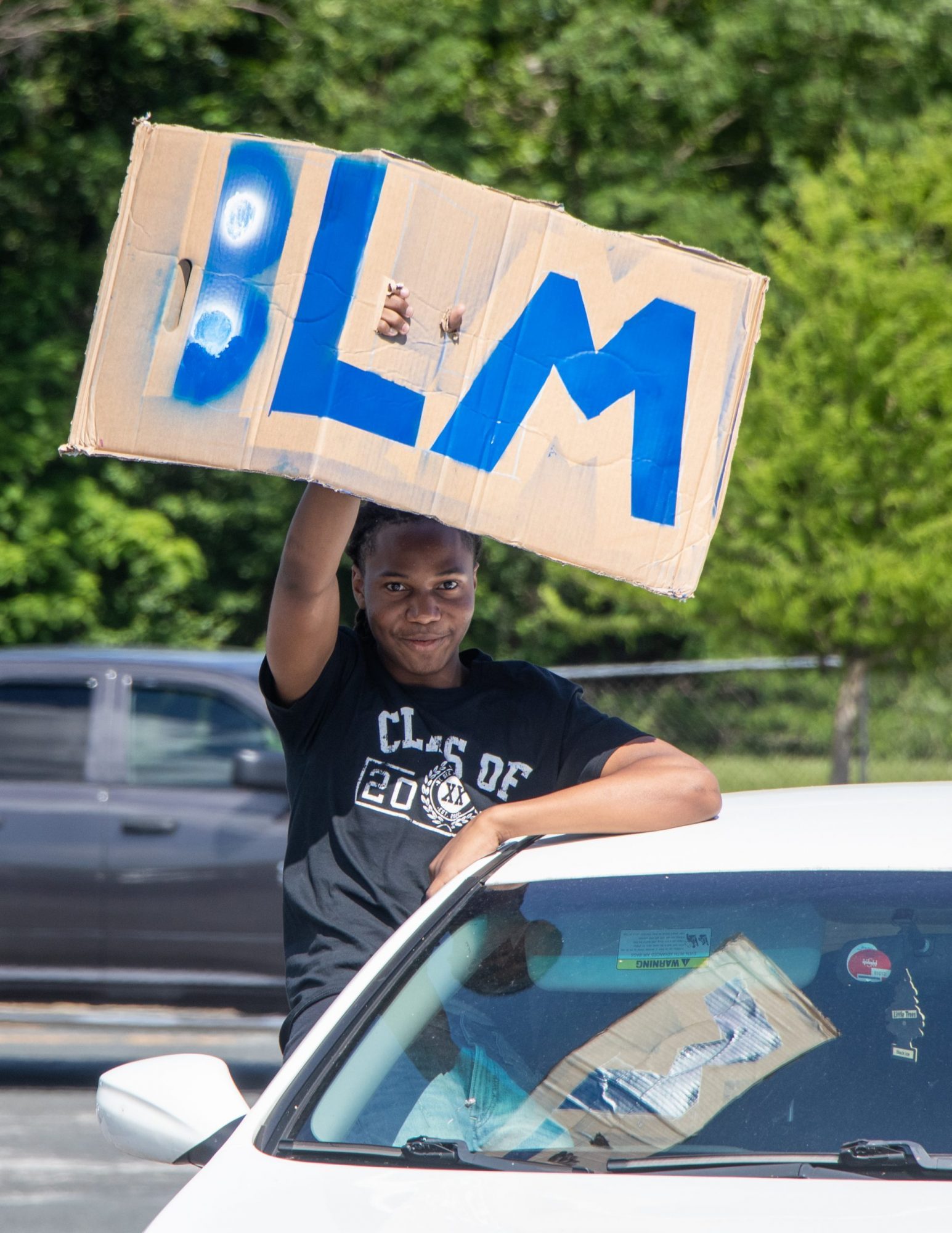

While some cars were adorned with posters, others were covered in statements such as “Black Lives Matter” and “No Justice, No Peace.”

Matthew Miller sat on the sunroof of his Jeep with his girlfriend and two-year-old son, Legend, who held a sign that read, “My life matters even @ two!”

Miller said he was moved to join the protest because of the injustices he’s seen against black people across the country — and the world. Coming together in support of the Black Lives Matter movement will change the world, he said.

“I believe that this is the spark that can start something bigger,” he said.

Recently, Miller has been thinking a lot about police brutality — especially because he has a young son.

“We’ve got to teach our youth and our children [about police brutality], he said. “It’s going to be hard having those types of conversations.”

Other demonstrators, like Tamara Carrion, felt the sting of recent events on a more personal level.

“This hits a little closer because one of my best friends — her cousin was actually killed by Montgomery County police … about three months before Trayvon Martin,” Carrion said. “And he didn’t get any justice nor hashtag or anything.”

For Matthew Konoha, a 2020 graduate of Oxon Hill High School, the Black Lives Matter movement and Sunday’s protest are about much more than just his life. Konoha realizes that the movement is a revolution — something that will take time for its effects to be fully realized.

“I’m willing to keep fighting until that happens, and even if it takes 70 [years], I’m okay with that. I feel like the main basis for why this needs to be done is mainly for youth at this point. They’re the future,” he said. “This is for everyone in America, whether [they’re] white, black, Hispanic, Asian. This is teaching the youth what’s right and wrong.”

Kwynci Fields, another demonstrator, echoed similar sentiments.

“I’m here today because I just want to make sure that I make a difference for my future children. I don’t want my children to grow up and feel like they’re less than in a world that looks at them differently just because of the color of their skin,” Fields said.

For others, such as Breana Welch, the protest wasn’t just about ensuring a better world for future generations — it was also about making others aware of the Black Lives Matter movement and the fight to end white supremacy.

“I am here to spread awareness to those who may not know or may not understand why we’re out here,” Welch said. “Just to show face and be a voice in this era right now.”

After protesters finished decorating their cars with posters and chalk, Leah Key, a co-organizer of the procession, asked everyone to gather in the center of the parking lot for some brief remarks.

Prince George’s County is one of the wealthiest black counties in the country, she said. But even though the county has a thriving black community, Key emphasized that its residents continue to be impacted by systemic injustices.

“This is a peaceful protest, but we do stand with our brothers and sisters across the country in whatever way they decide to process,” she said.

After the organizers finished speaking, about 100 cars lined up to exit the parking lot. With police escorts leading the way, the protest began its seven-mile drive to Washington, D.C.’s Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium.

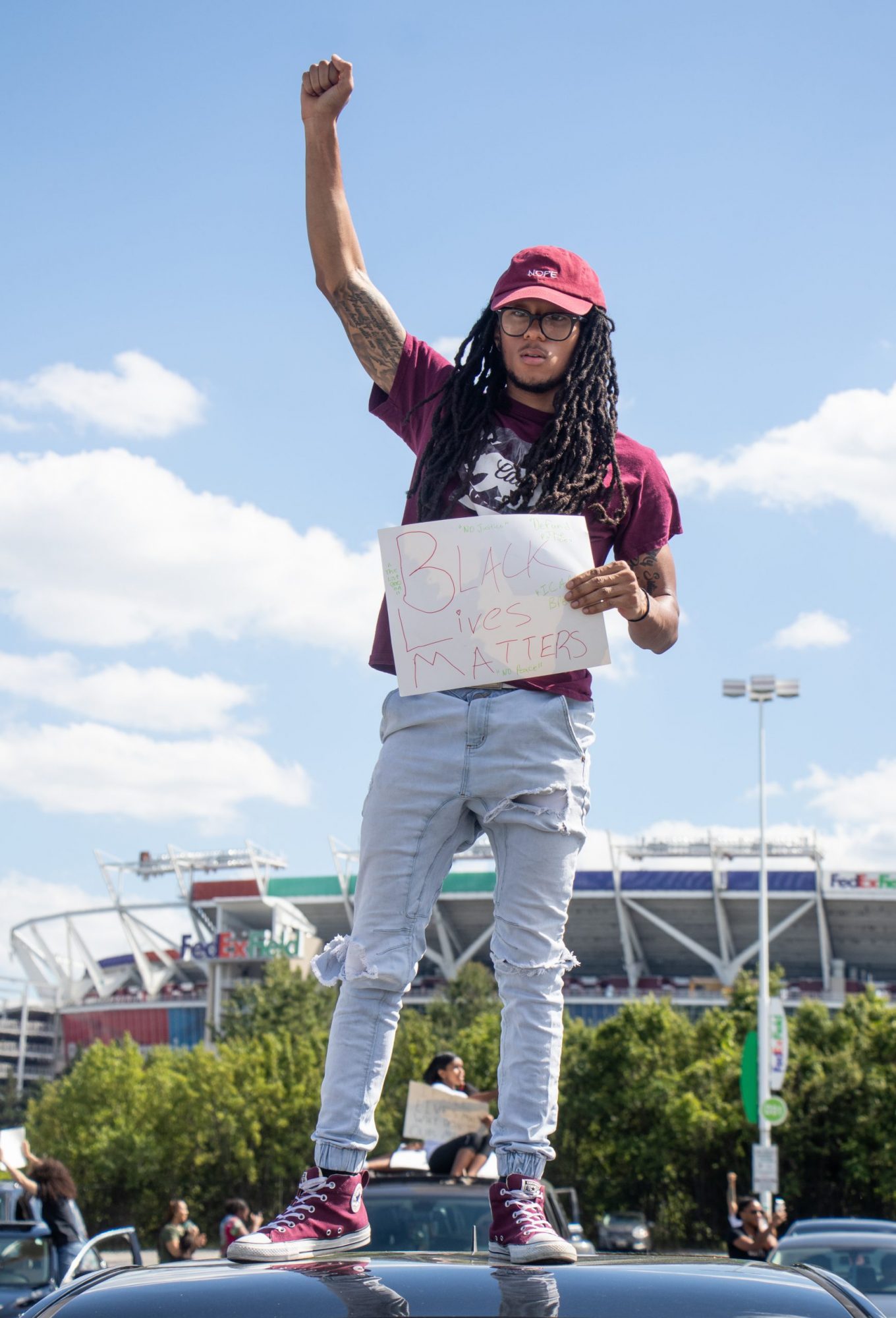

As the procession of cars circled the stadium, demonstrators honked their car horns and raised their fists, cheering.

Following its drive around the stadium, the protest circled back to its starting point. Along the way, cars driving past the procession stopped in the middle of the street, drivers honking their horns and raising their fists high in the air in support. Pedestrians did the same, with some people along the route exiting their homes to film the procession and wave the protesters on.

A few parked cars revved their engines, which echoed throughout the lot.

Pulling in one after the other, protesters began spilling out of their cars, clapping and cheering. Some protesters even climbed onto their roofs, holding up signs that read “Am I Next?” and “Black Lives Matter,” while others stuck out through their sunroofs, doing the same.

The crowd convened for one final meeting, Key thanked the crowd for coming and announced that another car caravan protest would meet at the parking lot next Sunday.

For Key’s mother, Loralyn Mayo, the protest was all about showing the community’s young people that they are supported.

“We know right from wrong,” she said. “We have to stand up for what’s right.”