Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

As we approach yet another month of the pandemic, the race to develop a vaccine against the novel coronavirus continues. A vaccine would be the best weapon against the spread of the virus and would ease our collective anxiety about getting sick.

However, health officials estimate that a working vaccine may not be widely available for another 12 to 18 months, at the earliest. And that’s only if we fast-track its development, which isn’t possible without relaxing certain scientific standards and safety protocols, such as thorough phase-by-phase clinical trials.

Therein lies the problem with biomedical development: It’s slow and often ends in failure. Drug development typically includes years of scientific research, multiple phases of clinical trials, manufacturing, approval and distribution. Normally, clinical research is a long-term endeavor where failure is often the norm. Even if a researcher successfully secures funding, performs the experiments and publishes the results, a new treatment must go through multiple clinical trials on human test subjects. Less than 10 percent of drugs that make it to clinical trials are ultimately approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

A worldwide pandemic may warrant some exceptions. In an effort to speed up vaccine research, one biotech company skipped the animal safety trials that are normally required before clinical testing on humans. Another global trial by the World Health Organization doesn’t use a placebo control.

It’s tempting to use an unproven vaccine under such extenuating circumstances. But without rigorous scientific trials, these drugs could have dangerous health effects and fuel mistrust in vaccines.

So, if it’s too risky to use unproven vaccines, what’s the solution next time there’s an outbreak of some contagious disease? The way to speed up the process without compromising safety: Be prepared from the start. We should’ve established centralized outbreak response teams among different health sectors to do just that.

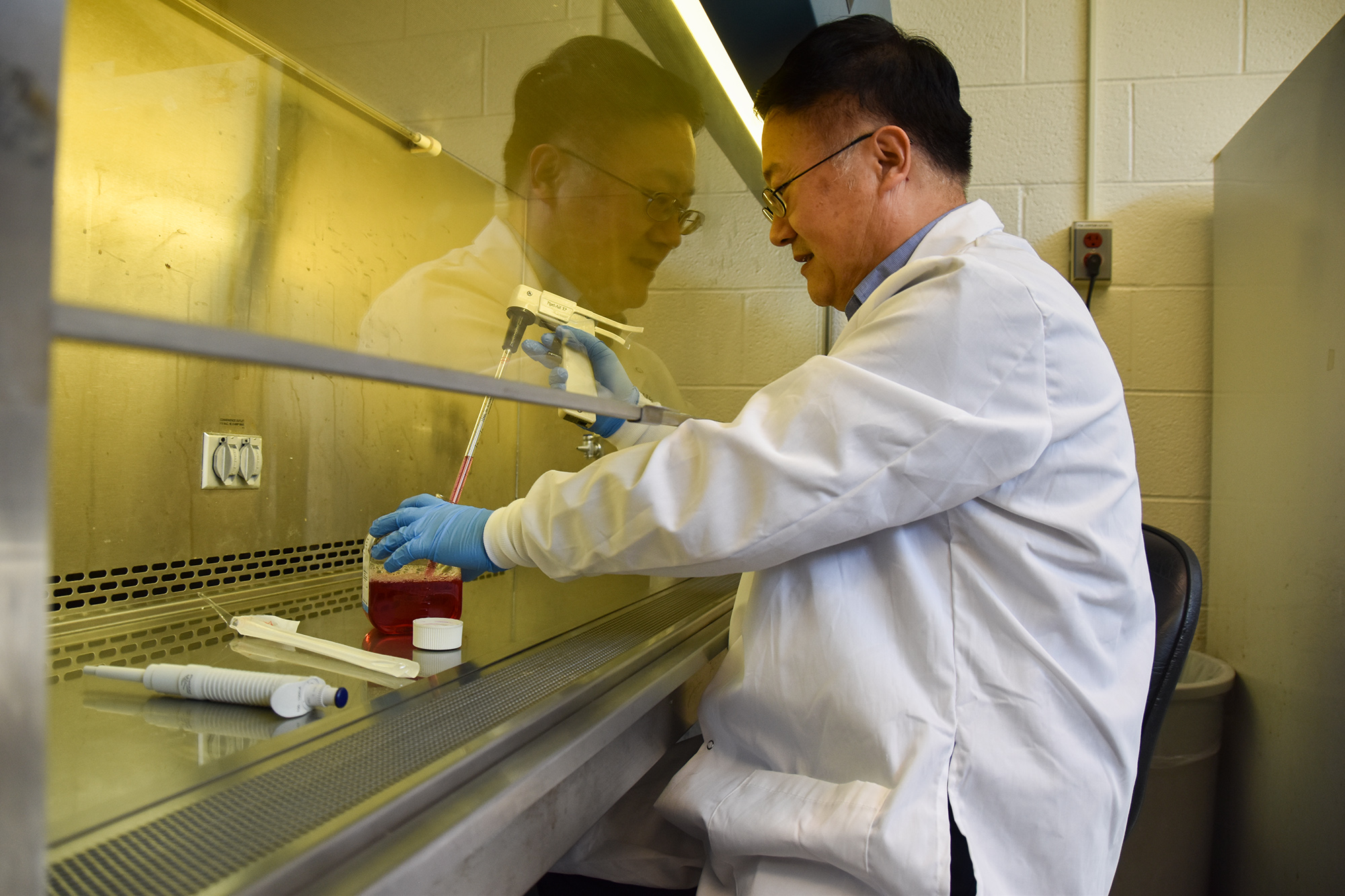

In Maryland, for example, many biotech companies have emerged as frontrunners in the race to produce a coronavirus vaccine. What distinguishes Maryland as a powerhouse is not just its sizable biomedical sector, but also the fact that these labs were preparing for a global disease outbreak in the first place.

Maryland represents a crossroads of the academic, federal and private sectors in biomedical research. Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland at Baltimore are major research universities currently working on COVID-19 projects. The National Institutes of Health and the FDA are both instrumental in the state’s presence in health research. Private companies in the region work on gene and cell therapies, as well as vaccines. Emergent BioSolutions, a company in Gaithersburg, has played a role in producing possible vaccines against anthrax and the Ebola and Zika viruses.

Using this to its advantage, the Maryland Tech Council has formed a COVID-19 coalition of companies “to share information about where to locate supplies, find lab space and encourage cooperation.”

The idea of a coalition of research groups is already a huge step toward emergency preparedness. In states without the same biomedical infrastructure as Maryland, this is one way that labs can stay connected in order to prepare for future emergencies. Science is already a collaborative field driven by the peer-review system. By taking advantage of the cooperative nature of science, it optimizes the resources shared across multiple groups.

A centralized outbreak response team that can share ideas and resources amongst its members has proven to be essential now more than ever. President Trump disbanded the National Security Council pandemic response unit in 2018. Public health officials — who have warned the White House about the potential for dangerous outbreaks for many years — partly attributed our “sluggish domestic response” to the coronavirus to Trump’s decision. Transparency and collaboration between the government, the public health sector and private and academic institutions would help us prepare for the next emergency before it even reaches the U.S.

Establishing centralized groups to promote collaboration encourages solidarity, readiness and the sharing of resources. Not only will this speed up the research and testing timeline of future drug development, but it will also jump-start our response to scientific emergencies. We’ll be able to understand outbreaks as a whole instead of wasting resources by working on a pandemic-to-pandemic basis. Rather than compromising clinical trials or using unproven vaccines, the best way to save the maximum number of lives is to anticipate the danger before it even starts.

Allison Cochrane is a junior biology major. She can be reached at allisonc@umd.edu.