Before the University of Maryland’s campus shut down, student volunteers manned the Help Center’s crisis line seven days a week.

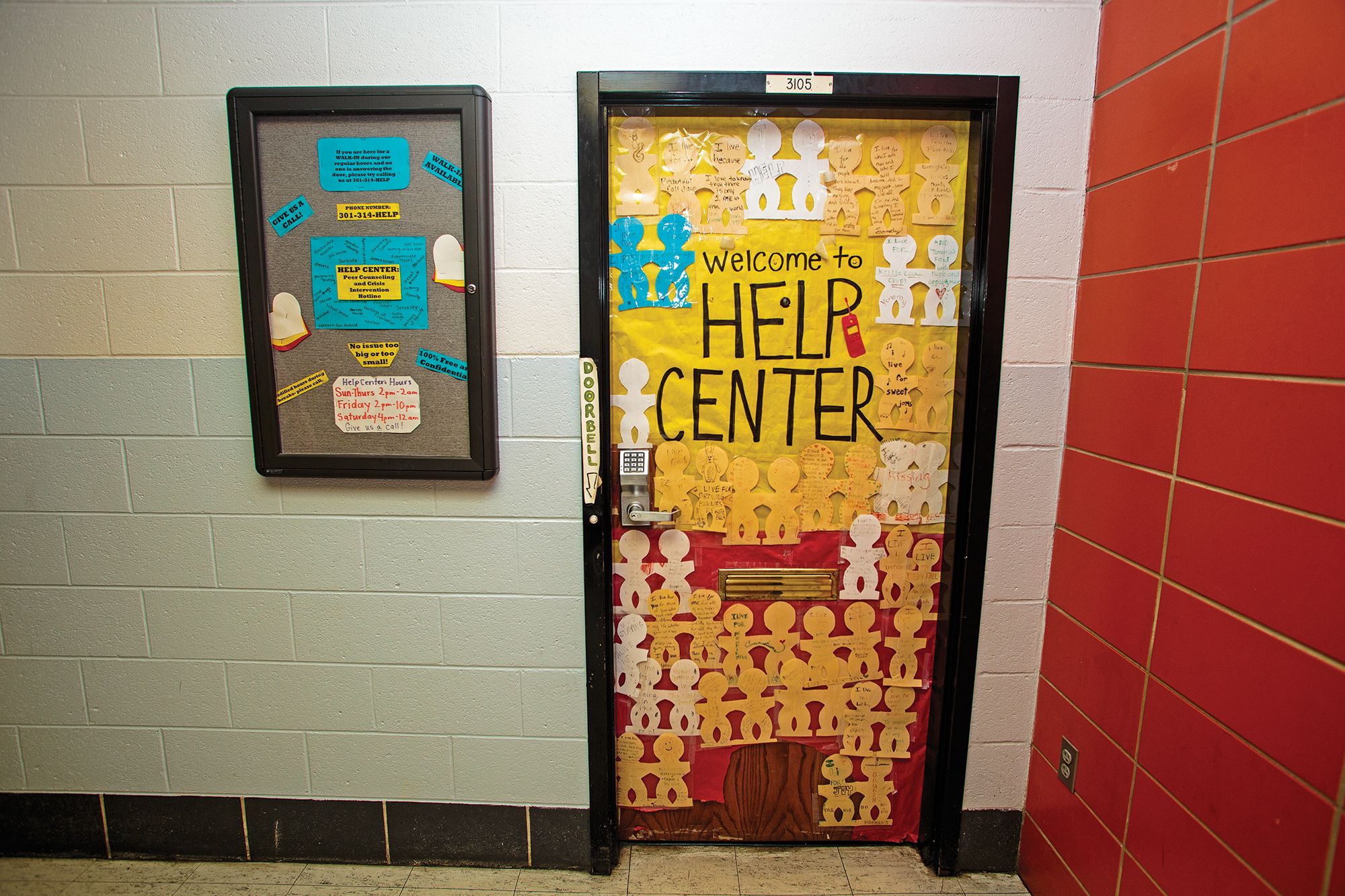

They’d work out of a small office tucked into a corner above South Campus Dining Hall, fielding calls and walk-in appointments from students in distress. They’d listen and connect students with mental health resources.

But the organization hasn’t been able to operate since students were ordered to leave the university’s campus over a month ago due to the spread of the novel coronavirus. And now, its volunteers are struggling with a sense of helplessness during a time when they feel like they’re most needed.

“It doesn’t necessarily feel like I’m making much of a difference, which is the reason that I signed up for the organization and I joined to begin with,” said volunteer Logan Dechter, a senior psychology and Spanish major.

The Help Center is a peer counseling and crisis intervention hotline that began in 1970, originally operating out of an off-campus house. Its services — which include pregnancy tests in addition to mental health support — are free and anonymous.

“I think that in times like this, people just want to be able to talk to someone and kind of figure stuff out, and I think that the Help Center could really be used to do something like that,” said volunteer Matt Leichman, a sophomore communication major. “It’s a shame that we’re not able to.”

[Read more: UMD counseling center braces for uptick in students seeking help during COVID-19 pandemic]

Volunteers are working to come up with new ways to support students, said Josh Lang, president of the Help Center and a senior criminology and criminal justice major. But the center’s commitment to confidentiality makes that difficult. Back in their offices, volunteers use landline phones that are covered to hide incoming numbers. They can’t provide counseling from their personal cell phones.

The pandemic has posed a barrier for trainees. For about two semesters, trainees learn from peer counselors in a rigorous training course to prepare them for the demands of the job. But the final test is in-person.

Leanna Rathbun, a sophomore government and politics major, is at the very last stage in her training. She’s not sure when she’ll be able to take the test, become an official counselor and start volunteering.

The situation leaves her, and the center as a whole, at a standstill, she said.

“We have so little counselors and so many people graduating, that it’s really set the organization back,” Rathburn said. “These are all people that want to help others and aren’t able to.”

Despite the setbacks, volunteers are trying to compensate. The center is posting resources and advice on its Instagram page and setting up a crisis text-line — although that idea is still in a preliminary research phase, Lang said.

And even though the center can’t be there for students right now, some volunteers are bringing the skills it taught them into their personal lives: checking up on friends and family and posting encouraging messages on social media.

Aarushi Malhotra, a freshman public health science major, has been posting messages promoting positivity on her Snapchat. They say things such as, “Have a wonderful day!” Though the act is minimal, Malhotra firmly believes that the messages could make a bigger difference than people realize.

No one alive has lived through a pandemic of this scale, Lang said, meaning there’s no clear place to turn for answers. So, he said, individuals are stepping up to care for each other.

“During this time, it’s really important that we’re talking with each other and doing our best to keep each other sane,” he said. “That’s the only way we’re going to make it through this.”

[Read more: UMD campus advocates worry about emotional impact of virtual sexual misconduct hearings]

CORRECTION: Due to a reporting error, a previous version of this story mischaracterized the Help Center’s training system and recruitment status. Volunteers are trained by peer counselors, not by professional counselors. The recruitment process also finished before classes went online, but recruits are unable to take the final training test. In addition, the story misstated the year the Help Center was founded and misspelled Matt Leichman’s surname. This story has been updated.