University of Maryland researchers at the Maryland Transportation Institute have put together a comprehensive data platform analyzing nationwide adherence to social distancing orders.

The COVID-19 Impact Analysis Platform launched mid-March in partnership with the university’s Center for Advanced Transportation Technology Laboratory. The site gives a glimpse into Americans’ attitudes toward a prolonged quarantine and how long it may take before it’s safe for the country to reopen.

As the coronavirus began to spread, researchers noticed a rapid increase in social distancing. Those numbers later began to stagnate and have since begun to drop. The researchers plan to keep the data platform up for at least the next few months, said Sepehr Ghader, the project’s manager and the assistant director of the transportation institute.

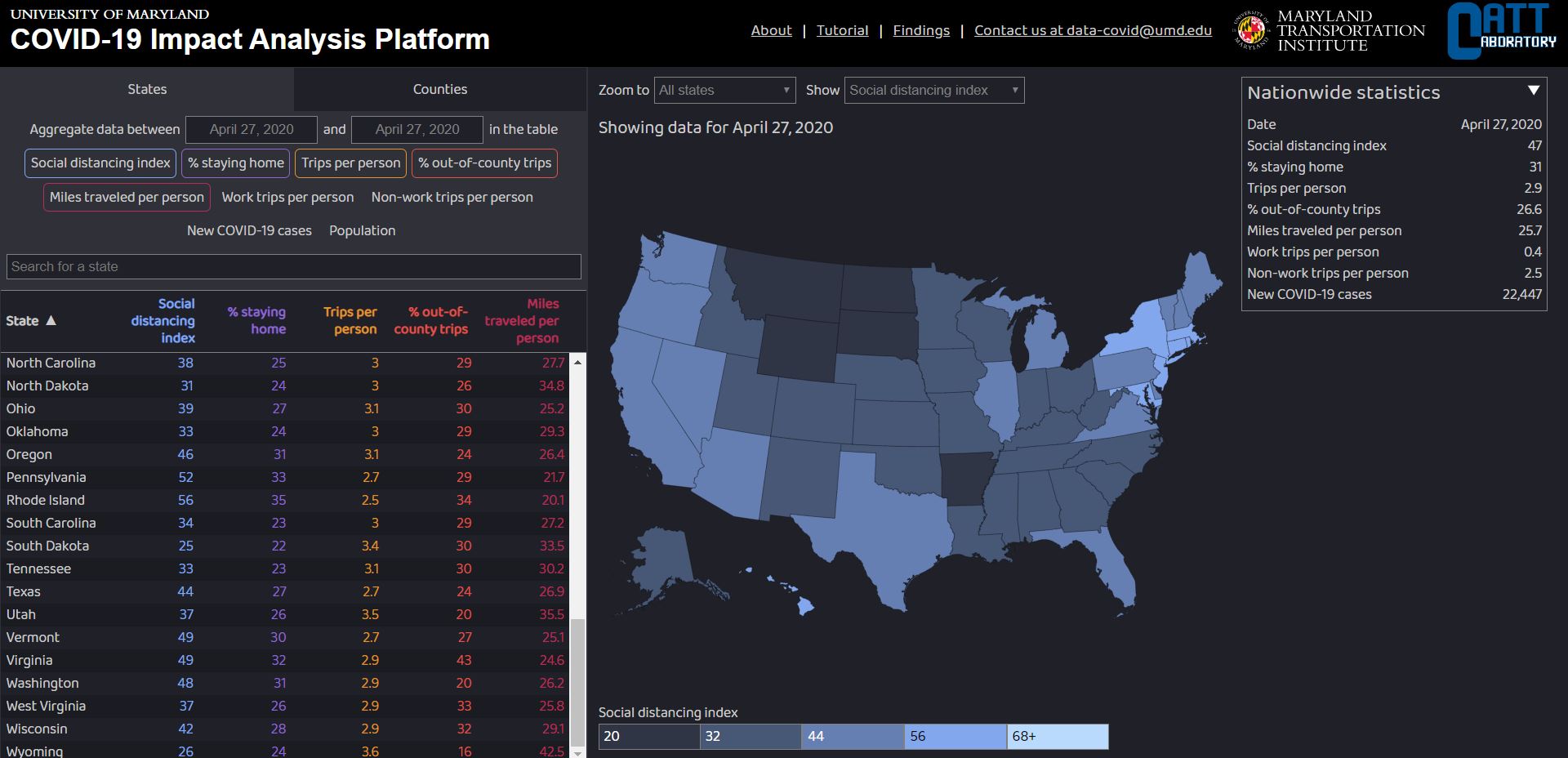

With anonymized phone and vehicle data from 10 million Americans, the researchers analyzed different factors such as the miles traveled per person, the average number of trips people take out of their homes and the percentage of people staying at home. These elements combine to create a social distancing index for each county and state in the country.

The index is reflected in a number from 0 to 100 that represents the extent to which residents and visitors are practicing social distancing within that area.

“Our main goal was to inform decision makers about their policies and the behavior of their communities,” Ghader said.

In mid-March, researchers noticed a general spike upward in social distancing among Americans, seeing the percentage of people staying home nationwide increased from 20 percent to 35 percent — which continued after President Trump announced a national emergency on March 13, Ghader said.

But two weeks later, just as individual states began to implement stay-at-home orders, adherence to social distancing reached a plateau, Ghader said. After the initial jump, it stagnated at 35 percent for the next three weeks, according to the transportation institute’s website.

[Read more: USM assembles COVID-19 task force to mobilize research, guide state policy]

Researchers referred to this phenomenon as “social distancing inertia.”

“After a while we see that the people, even in states where the number of new COVID cases are increasing … are practicing the same level of social distancing and staying at home,” said Aref Darzi, a doctoral student in transportation engineering who’s been working on the project.

The trend grew more disheartening on April 14: For the first time since social distancing measures were first put in place, social distancing indexes began to decrease universally, a sign of “quarantine fatigue.”

Though the number of COVID-19 cases continues to rise throughout the country — surpassing one million on April 28 — and most stay-at-home orders remain in place, Americans are beginning to venture outside their homes more.

As of April 24, 48 states saw a reduction in their social distancing indexes. Maryland had a 3 point reduction, and the percentage of people staying home in Prince George’s County fell from 37 percent to 34 percent within that time, according data cited in The Washington Post.

The first signs of quarantine fatigue in the data occurred before Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee became the first three states to reopen public facilities beginning the week of April 20.

[Read more: UMD engineers are producing masks and hand sanitizer for local healthcare workers]

Sandra Quinn, a professor in the public health school, notes that many essential workers do not have the option to social distance, and there is a “natural restlessness” that comes with being in one space for so long that could help explain quarantine fatigue.

But she also attributes social distancing disparities to “different messages” from government officials. While certain state leaders have adamantly stressed the need to stay home, others — including Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis — have taken actions that downplay the threat of the virus to their constituents, she said.

“Right now in the U.S., we have a great variation in the messages about social distancing and staying at home,” she said. “There are people who are listening to a governor who said ‘Oh, it’s not a big deal,’ and saying ‘I guess I can go out.’ We have such different messages for the American public to try to understand — that is confusing.”

Hongjie Liu, the chair of epidemiology and biostatistics in the public health school, has been analyzing the virus’ spread in Maryland since the state’s stay-at-home order was implemented. Social distancing measures are working, he said, but the virus is still far from contained, which makes the lack of social distancing more concerning.

“At this moment, especially in Maryland, the epidemic is still there. If we relax social distance, or if we leave social distancing, it is highly likely people will be infected with close contacts,” Liu said. “Consequently, the epidemic will jump up again.”

Both experts emphasized the need for governments and health organizations to educate the public on the reasons for social distancing measures, rather than simply asking people to follow stay-at-home orders.

In recent days, researchers working on the data analysis platform have presented their results to state officials in an effort to help guide policymaking going forward. They are currently developing another data measure — what Ghader refers to as a tool for social and economic reopening — that integrates 26 different economic and healthcare measures, which could further aid officials considering reopening plans.

The tool will take into account certain criteria, such as any decline in cases over a two-week period, the rate of positive tests in that area or the availability of hospital beds. Researchers will add these measures into the existing data on the platform so that different state leaders can see where they rank compared to others in terms of combating the disease, Ghader said.

“So far what we have seen is that most of the states are not passing the [gateway] criteria identified by the White House, but still we are seeing them reopen,” Ghader said.