Trevor Quinn was the funniest person Mike Mullee has ever met.

“And that is without exaggeration,” Mullee said.

He’d make a fool of himself, strolling along Easton Hall’s fourth floor in an old taco costume with a goofy smile on his face. He’d send absurd polls to his floor’s group chat — asking questions that would’ve made no sense to a stranger.

“What nomenclature should I use to describe my second offspring?” one read. The options weren’t any less odd — Quavo Huncho (a trap album), Gebremariam (a professor at the University of Maryland), Deluxe Cheese, or Steve Buscemi, Jr.

Those close to Trevor say they’ll miss that unique approach to humor. They’ll remember him as thoughtful, bright and hardworking. They’ll mourn the loss of his kind and gentle disposition.

Quinn, a junior aerospace engineering major at the University of Maryland, died last week at the age of 20 from unknown causes, according to his family.

Mullee, a junior mechanical engineering major, met Trevor during their freshman year. They were both in the Gemstone honors program, and would later be placed in the same laboratory. The pair would often plan to walk together to the lab session — a journey that took no longer than two minutes.

“If I hadn’t seen him yet that day, I’d look forward to seeing him then,” Mullee said. “Because I knew … that those two minutes would just be great.”

In the lab, Trevor didn’t want to be a leader. He’d ask Mullee to tell him what he needed to do, and he would make sure to do it well. In a way, though, he led by example — inspiring his classmates with his dedication to not just get through their challenging work, but to understand it.

Bailey Konold, a junior aerospace engineering major, recalls the nights they would spend studying. Trevor would often lock himself in his room, Konold said, and not come out until he knew how to solve complex equations like the back of his hand. Then, he’d sit down with Konold and help him.

“He certainly carried me through quite a few of my classes,” Konold said.

Chris Hoffmann, also a junior aerospace engineering major, said Trevor — who was always “the first to crack a joke about how impossible the homework was to do, even though he was the one who did it the best” — inspired him to take more pride in his work. He made him rethink his approach to school.

Trevor was brilliant, his friends said, but a stranger wouldn’t know it. After the grades for an engineering exam were released, his friends would complain about someone who had messed up the curve. They’d all wonder who got that score, higher by 20 to 30 points.

Trevor didn’t like to be the center of attention. So he played along.

His mannerisms were stoic, said his Gemstone adviser, Bryan Quinn, and Trevor kept his cool even during the most stressful days in the lab. At a glance, he came across as serious — but a moment later, he’d have the entire team laughing.

“He’s kind of like a ninja with his personality,” Bryan Quinn said. “He is just very calm, quiet and everything else, and then he just pulls this funny, weird joke.”

When Trevor first met Julie Pitzer back in their high school calculus class, that signature humor fell flat. But after more than three years of dating, Pitzer got used to it.

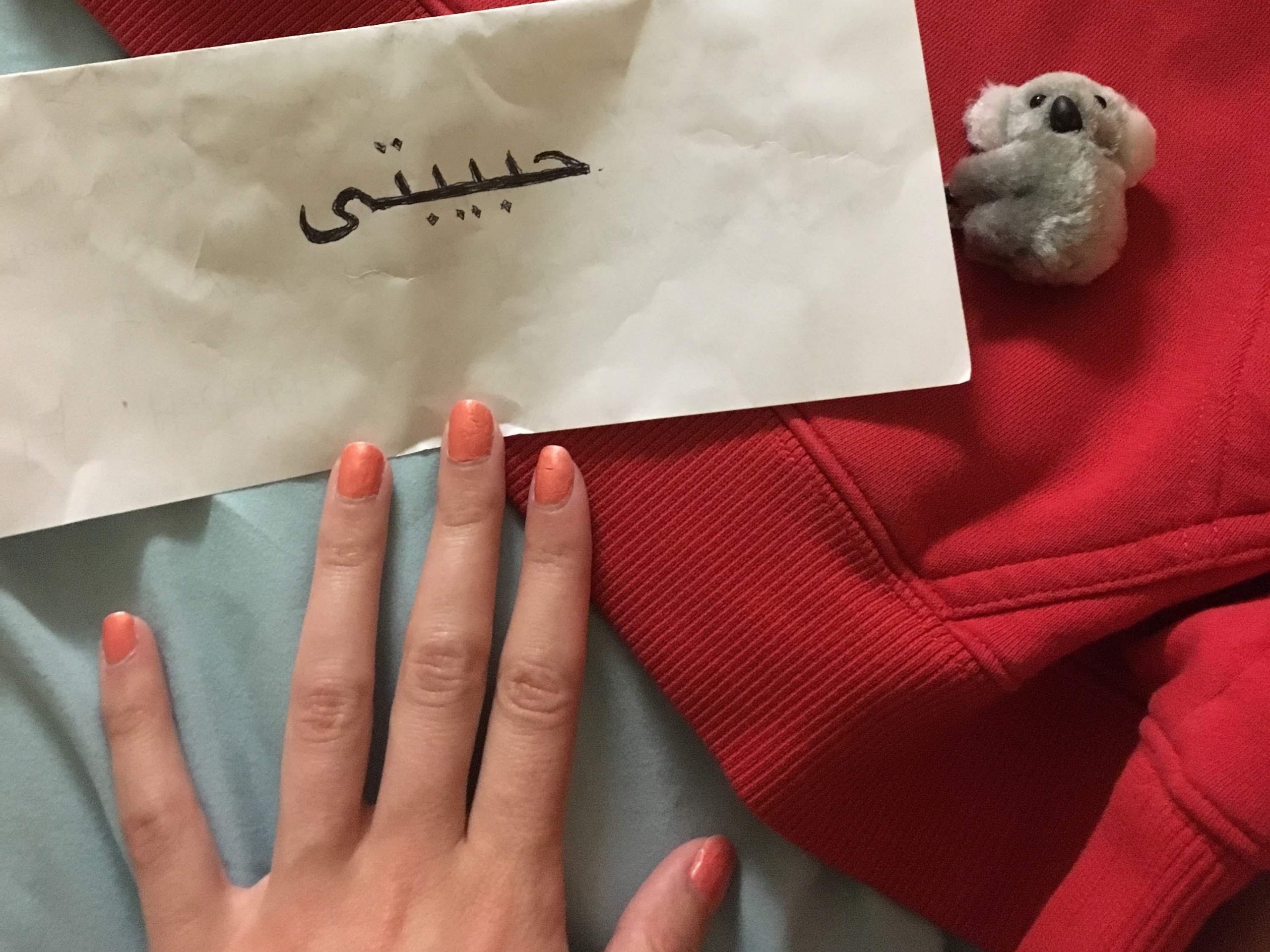

If he was serious in class and a jokester with his friends, around Pitzer, he was sweet. He texted her photos of the black squirrels he would see on campus. He wrote her notes in Arabic, which her family speaks, and he tried to use expressions he’d learned.

One night, Pitzer, a junior bioengineering major, was particularly stressed, preparing for three exams she had the next day. Trevor texted her, asking her to go down to the lobby of her building for a minute.

When she did, he was there, holding a card and chocolate bars. He had walked all the way from his apartment in The Varsity to hers in The Enclave.

The note had a big monkey on the front, and the inside had three smaller monkeys — one holding a chemistry flask, the other with cells around it, and the third with a strand of DNA — each representing one of her exams.

“Don’t worry,” the note read. “Everything’s gonna be okay.”

He gave her a hug and a kiss and told her to get back to studying.

Trevor was known for small gestures like that, said his mother, Jesse Quinn — things he didn’t have to do. Her most special moments with her son took place in the family car. Even though they lived across the street from his high school, Jesse would drive him each morning.

After he went to college, she treasured their car-ride conversations even more. She’d pick Trevor up every Friday, drive him back to his hometown of Bel Air, and return him to College Park that Sunday.

In the hours up and down I-95, it was just the two of them. He would try to explain his classwork to her. He’d tell her funny stories about his friends. He’d promise to take care of her and his stepdad, Douglas Nichols, one day, swearing to buy them a house by the beach.

“He would say little,” Jesse said, recalling the conversations. “But it was a lot.”

Trevor didn’t say much that night he dropped off the note for Pitzer, either, she remembered.

But it was enough.

“If you ever need me,” he told her, “I’m there.”