By Lyna Bentahar and Clara Longo de Freitas

Staff writers

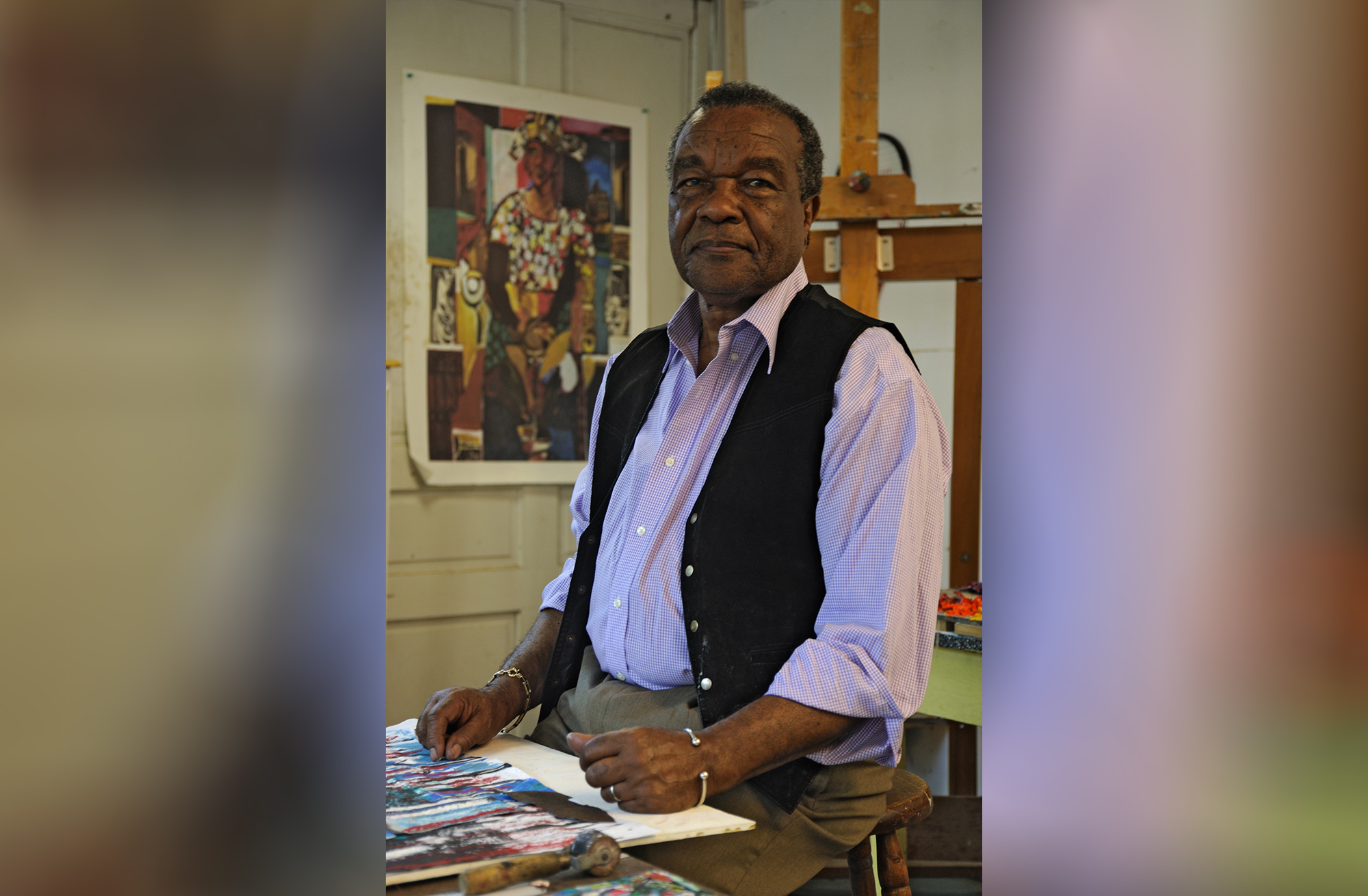

David Driskell made it a point to attend the opening for nearly every art exhibition that took place in the University of Maryland center bearing his name.

And he was usually one of the last people to leave, said his longtime colleague Dorit Yaron. Students would approach Driskell, asking him to review their work. He would listen, looking them straight in the eye. It didn’t matter that he was a giant in the field, that they were still pursuing undergraduate degrees — they would have his full, undivided attention.

“He just really found time for everybody,” said Yaron, deputy director of this university’s David C. Driskell Center.

Driskell, a famed artist, curator and historian considered one of the greatest authorities on African American art, is remembered by those who knew him as a gentle, humble man with a drive to support young black artists. He died last week of complications from the novel coronavirus at the age of 88.

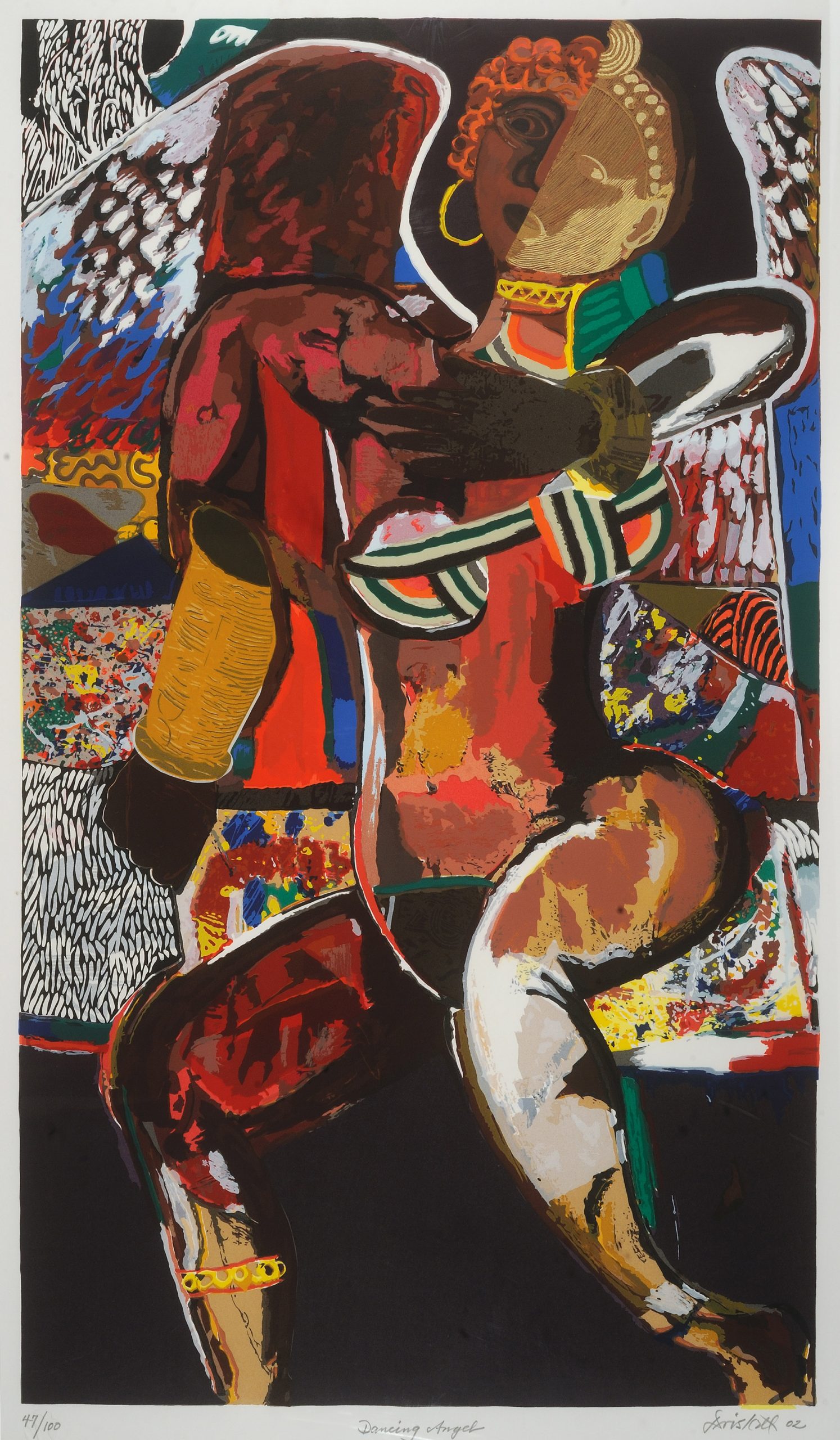

His paintings depicted the range of emotion in African American history. In heavy, dark strokes, he immortalized Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy who was brutally murdered by two white men. But, sometimes in vivid gouache, sometimes in oil, he’d also wash the brush against canvas in confident dances until it revealed bright pride for African culture.

Driskell’s 1976 exhibition, “Two Centuries of Black American Art: 1750-1950,” was monumental in bringing African American art to prominence in a culture that largely viewed American art as exclusively white or Western.

Driskell joined the faculty of this university in 1977. A year later, he became the second chairperson of the newly-created art department.

“I thought of him as Superman,” said W.C. Richardson, chair of this university’s art department, who was a professor when Driskell first held the position. “There were so many stages to his life along the way. And he could tell you stories about all of them.”

Established in 2001, the Driskell Center at the university aims to uphold Driskell’s legacy, serving as a place to celebrate and uplift black artists across the country. The center keeps an archive of Driskell’s research, publications, photographs, audio files and a number of artworks from his personal collection, and hosts regular exhibitions featuring the work of black artists.

It was the synthesis of who he was — his ideas, his scholarship, his paintings — that made Driskell so remarkable, said Richardson.

“He’s an institution of himself,” he said.

Driskell stayed at the university until his retirement in 1998. Two years later, President Bill Clinton awarded him the National Humanities Medal for his service to the field of African American art history.

As a historian, Driskell published and contributed to essays focused on the Harlem Renaissance and both early and contemporary forms of African American art. Julie McGee, who wrote the biography David C. Driskell: Artist and Scholar, wrote that his assessment of black art established it as a “legitimate and distinct field of study.”

Throughout his career, Driskell would come to know artists such as Jacob Lawrence, the first black American to be recognized in the Museum of Modern Art, and Romare Bearden, awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1987.

In turn, Driskell mentored artists such as Jefferson Pinder, now the dean of faculty at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago.

Driskell said making art was a priest-like calling, Pinder recalled. And it’s “almost impossible to do what he has done,” Pinder added — no easy task to accomplish so much as a historian while simultaneously gathering so much acclaim as an artist.

But people who knew Driskell say the grandiosity of his career could hardly be recognized in the man himself. Colleagues and friends fondly recall his generous, unassuming nature. Kaela Walker, the Driskell Center’s art registrar and a senior art history major, said he presented himself with an “overwhelming self-assurance and calmness.”

Driskell wanted to recognize the artists he mentored rather than his own list of accolades, Walker said.

“It all came down to his personality,” Pinder said. “He would allow you to forget who he was.”

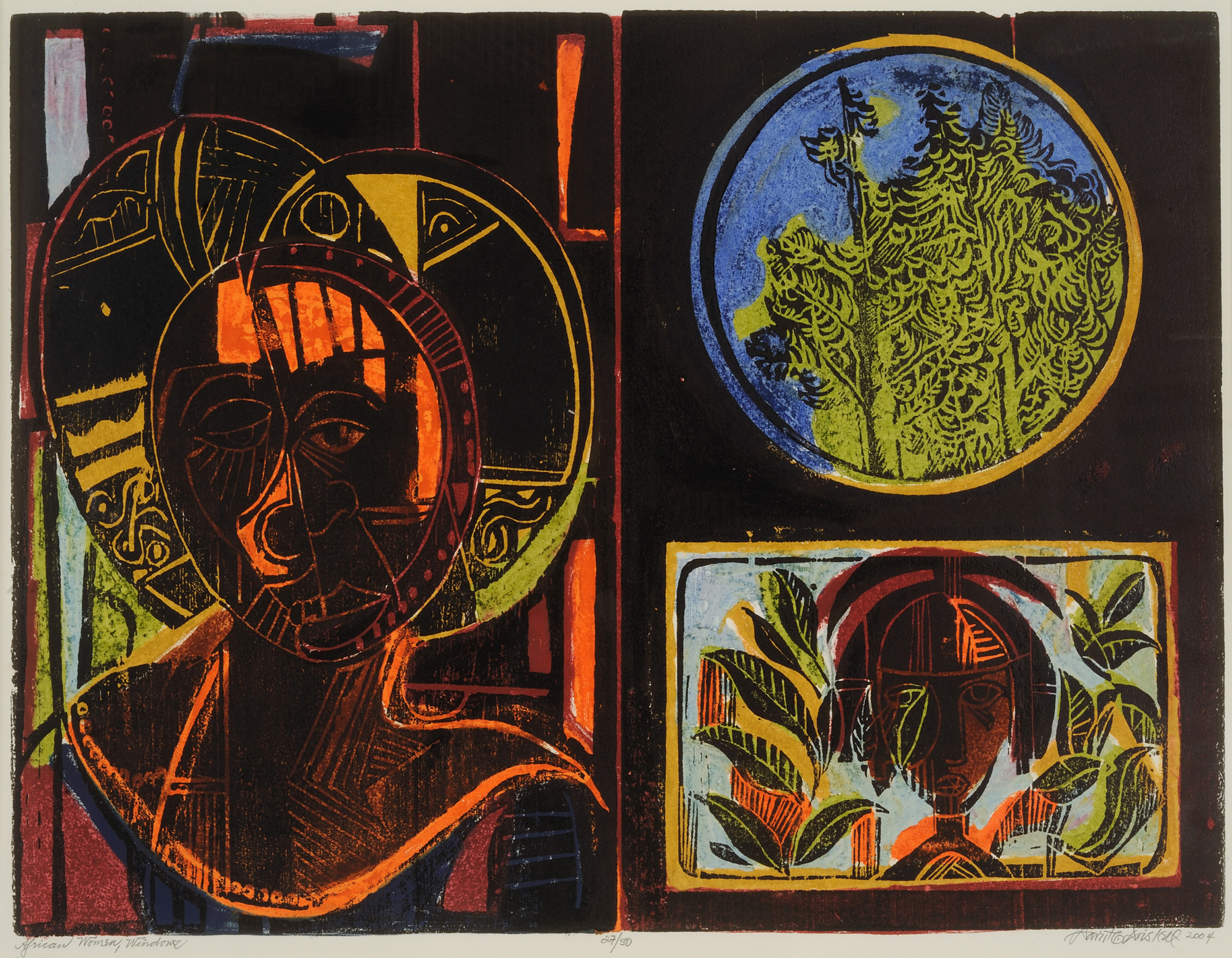

Though his colleagues remember his warmth, it was the cool woods of Maine that had a hold on Driskell throughout his career, Yaron said. He first fell in love with the pine trees there in the 1950s.

It wasn’t uncommon for artists to feel drawn to the state. Many had summer houses there, Yaron added. Driskell promised to himself he would, too, someday — and he did. Yaron thinks that house might have given Driskell a sense of achievement, might have confirmed to him that he’d really made it in the majority-white world of professional art.

He could see the pine trees from his window, and they captivated him. For over 40 years, he painted them.

One of his paintings of a pine tree now rests in the Driskell Center, located in the Cole Field House at the University of Maryland. The artwork, painted in green and blue with passionate brushstrokes, dates to 1959.

Next spring, the room where that piece hangs will be the site of a large retrospective exhibit honoring Driskell’s career, said Maeve Bassett, a graduate assistant who works for the center. The event — which would have overlapped with Driskell’s 90th birthday — was in the works long before his death.

But now, it will take on an even more special meaning.

“I know they’re going to put just as much, if not more, dedication into it,” said Bassett, a second-year master student in the applied anthropology program. “That’s going to be a really great opportunity for people to learn about him.”