Patrick Stevens needed a moment. He needed a moment to look around and take it all in, the pure debauchery — and, at its worst, destruction — going on below him.

He wasn’t naive to the situation. It had occurred twice before, after all. But as Stevens stood on the crest of a hill near Knox Road watching the people running around and the bottles breaking and the fires burning and the clunky televisions and couches fueling those flames, he opted to observe.

He pulled out his notebook and wrote as much as he could, documenting the dissolution of civility around him, the outpouring of grief over Maryland men’s basketball’s blown 22-point lead to Duke in the 2001 Final Four — an outpouring that wound up costing $500,000 in damages.

“You’re just sort of like, ‘All right, well, this is happening,’” Stevens recalled.

Stevens, a former sports editor at The Diamondback, had covered his fair share of memorable moments. He was in Miami for the 2002 Orange Bowl — a resounding Terps defeat — and in Atlanta for the basketball team’s resounding success later that year. Those were great. Those stand out among his fondest Diamondback memories.

But those riots? Seeing Maryland basketball fans turn revelry and sorrow alike into bonfires? That’s one-of-a-kind. And that’s what keeps it vivid in Stevens’ memory nearly two decades later, as well as so many former Diamondback reporters who covered the early instances of a growing Maryland tradition.

“It was just so bizarre,” Stevens said. “It was not something you expected to run into.”

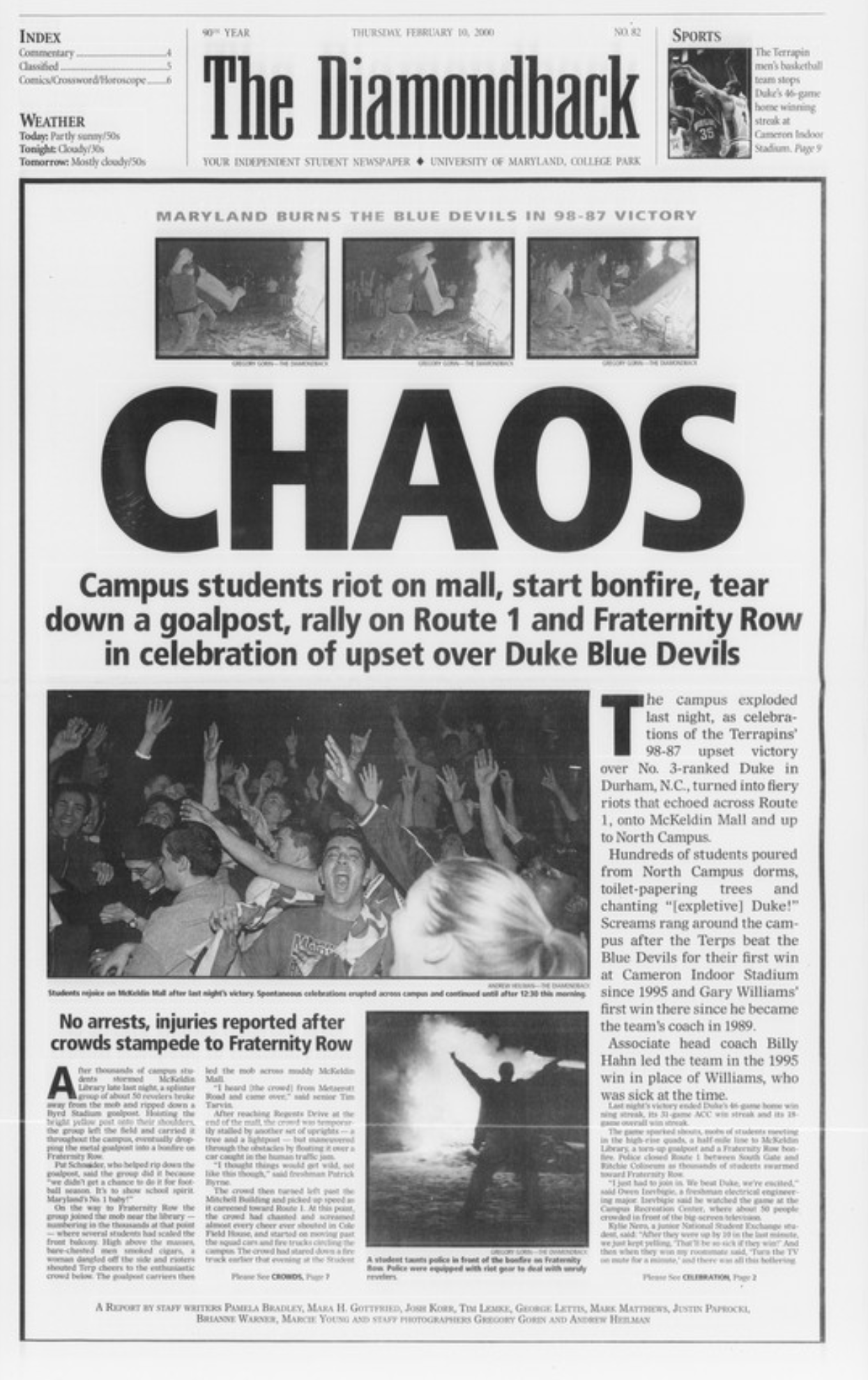

It was even less expected on Feb. 9, 2000. That’s when the Terps ended the Blue Devils’ 46-game home winning streak with a 98-87 victory — and that’s when those fans left behind in College Park began spilling out of bars, dorms and frat houses. That’s when The Diamondback newsroom began hearing rumors of a gathering near Fraternity Row, a celebration after a breakthrough at Cameron Indoor.

As reporters made the trek to the growing commotion, they realized what their night would suddenly involve. Couches from surrounding houses became kindling for a growing blaze; a giant Scooby Doo doll turned to ash, too, according to a Diamondback report; a torn-down goalpost from what was then called Byrd Stadium made its way through the campus on students’ shoulders before its addition to the fire.

And then Etan Horowitz, a former news writer and editor, laid eyes on the largest guy around. Matt Slaninka, a 7-foot-4 center who redshirted that year and hadn’t traveled to Durham, North Carolina, with the team, pranced around the bonfire as onlookers chanted, danced and fueled the flames.

“It was kind of the perfect storm of celebration and not thinking straight,” said Matt Sheehan, a former Diamondback editor in chief.

That’s a lot to take in, and a lot to turn around onto the front page of the next morning’s edition of The Diamondback.

But there it rested on newsstands the next day, “CHAOS” emblazoned across the top, with nine contributing reporters and the black-and-white photographs of revelers reveling and a couch up in smoke.

That word — “CHAOS” — has lasting power. But “chaos” and “riot” also proved to be somewhat contentious vocabulary. Tim Lemke, a former news editor, got into a debate with a professor over whether “riot” was the correct word.

Lemke’s professor had seen riots in the 1960s. Lemke saw fire on Feb. 9, 2000. He saw a mass of people running around, adding to those flames and breaking bottles. He eventually saw police in riot gear dispersing the crowd. But was it chaos?

“In retrospect, probably being, you know, a 40-year-old adult right now I look and think maybe a more measured explanation might have been more appropriate,” Lemke said. “But you also kind of have to think about it in context of the students and how they felt at the time and the moment. And I think we were able to capture just how significant it was.”

“In hindsight, it might have been a bit hyperbolic,” Sheehan said. “But it’s the beauty of student newspapers. You kind of have that freedom and flexibility.”

In that edition, the element of surprise was clear, said Jonathan Schuler, another former Diamondback editor in chief. In The Diamondback’s editorial section, there was no mention of the impromptu campfire down on Frat Row. Instead, a staff editorial chastised readers for not attending an event featuring black activist and essayist Dick Gregory earlier in the week.

That would change in later years, when riots began to shift from front-page news to the inside pages. The second raucous celebration — sprouting from another win at Cameron Indoor on Feb. 27, 2001 — earned the headline “ENCORE” splashed across the page, featuring images of another blaze and a soccer goal making its way to join the bonfire.

But the third — the one Stevens watched unfold down by Knox Road after the 2001 Final Four loss — only warranted a front-page tease, a biproduct of a cool-down period as Saturday night’s news waited for the Monday print paper.

“There’s sort of that old saying like, the first time is the first, the second time is a coincidence, the third time is a trend,” Schuler said. “And what we saw over the course of three years is a trend become sort of ingrained as culture. For better or for worse.”

The art of rioting has disappeared, perhaps a casualty of Maryland’s move to the Big Ten and the subsequent evaporation of yearly matchups with Duke.

But those print editions — flashy headlines and all — continue to convey the spirit of the rowdy reactions, the ones that spilled over into something beyond delight or dismay, turning parts of College Park into an inferno over wins and losses alike.