By: Arya Hodjat, Jillian Atelsek and Matt McDonald

Senior staff writers

On a November day in 1993, many readers looking to pick up a copy of this newspaper were greeted with an empty newsstand — and a flier.

“Due to its racist nature, The Diamondback will not be available today,” the note said. “Read a book!”

Lamont Clark remembers laughing when he saw that. Then vice president of the University of Maryland’s Black Student Union, he knew that marginalized students took issue with the paper’s coverage of their communities. That was a long-accepted fact. Clark normally turned to the school’s black publications instead, and he was used to feeling disappointed in The Diamondback.

That day, about 10,000 newspapers were snatched off more than 60 racks, wiping out a third of the publication’s daily editions.

“It was a legitimate form of protest,” Clark said. “The theft was about protesting the portrayal of black life on that campus.”

The archives of The Diamondback are littered with images of blackface and front-page headlines advertising minstrel shows. Reporters have decided not to cover stories important to minority students and botched many of the ones that they did.

Any examination of our history would be incomplete without highlighting a fundamental truth: Time and time again, this paper has failed its readers.

And though such failures affected people with a broad range of identities, the discriminatory treatment of black students and community members was often particularly glaring.

‘A tool of white supremacy’

In theaters on this campus throughout the 20th century, white performers would don blackface and act out caricatures of black people in comedy sketches as part of “Cotton Pickers’ Minstrel shows.”

The Diamondback promoted them consistently and zealously.

For example, the front page of the January 12, 1951 edition — which contains the news of the inauguration of Maryland Gov. Theodore McKeldin — awards prime real estate to advertising an upcoming show.

Those choices made The Diamondback a “tool of white supremacy,” said Andre Perry, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities.

Perry received a doctorate from this university’s education college in 2004. During his time on the campus, he dug into the school’s archives to research its racist traditions.

“When you’re a journalist,” Perry said, “you like to think that you are trained to remove yourself from that context in order to report on it.”

But immersed in the campus culture, writers and editors have the same “blinders on around race, around racism, that the rest of the community has,” he said.

Just a few weeks after this paper boasted a photo of a “blackface spiritual singer” assuming what it referred to as the “traditional pose,” the school’s Board of Regents ordered the university president to admit the institution’s first black undergraduate student, Hiram Whittle.

As courts and activists dragged U.S. schools slowly through the process of integration, the paper turned its focus toward a campus in turmoil. But its messaging on the topic was often mixed.

In a 1950 issue, The Diamondback printed an anonymous letter to the editor that blasted those who supported integration.

“The well-educated Negroes have stated that the Negro is far happier with his own race instead of mixing with us,” it read. “If non-segregation is allowed, this will mean inter-marriage, which I don’t believe anyone really wants.”

And even when the paper’s editors took a stand for equality — publishing anti-segregation editorials and condemning discrimination on the campus and in the city — they stopped short of endorsing earnest protest. In a 1954 editorial, the staff wrote that the idea of boycotting College Park restaurants that refused to serve black patrons was an “extreme radical” thought.

“We do not believe that drastic action need be taken in the matter,” it said.

The gaps

Harry Clifton “Curley” Byrd wore many hats for this university. From the 1910s to the 1930s, he held titles including head football coach, athletic director, assistant university president and vice president. In 1935, he became university president.

He was also an ardent segregationist. But that context didn’t appear to resonate with the editors of The Diamondback’s December 1, 1950 edition.

“Byrd Asks For Racial Ballot Test,” the front page read. Its sub-headline: “President Says Negroes Prefer Own Institutions To College Park.”

The only source quoted in the article is Byrd. And buried nine paragraphs in is the news that “recently, Parren Mitchell, another Negro, was admitted to the graduate school of sociology.” Mitchell was the school’s first-ever black student.

Much of the story of The Diamondback’s failings in later decades is apparent in gaps in its coverage — a byproduct of a campus where the needs of students of color have, for so long, been ignored.

That trend continued long after the most blatantly racist content faded from the paper’s pages. It outlasted the pro-segregationist columns and the jarring images of blackface, pointing to a wider — if quieter — bias.

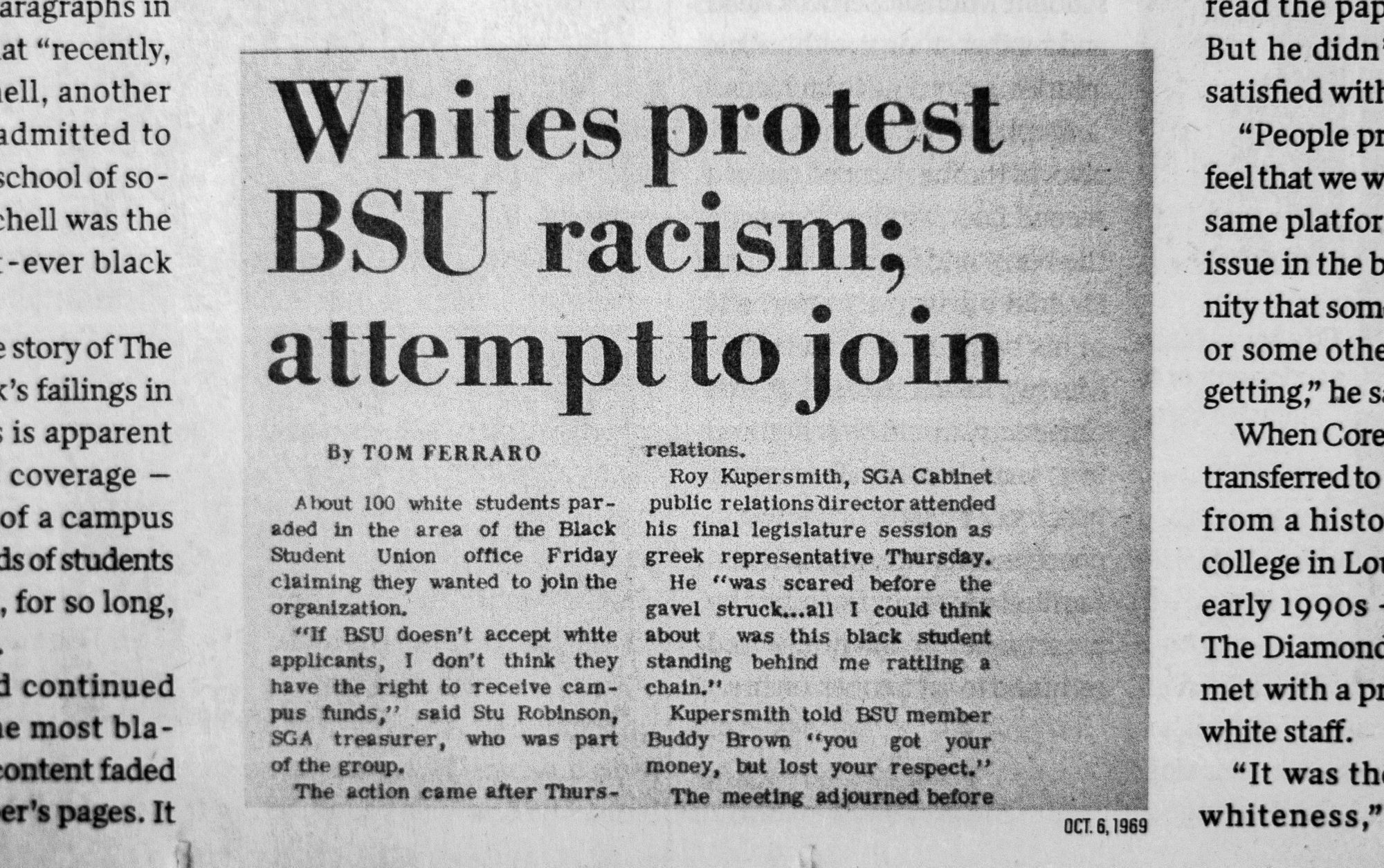

As the Black Student Union fought for increased SGA funding in 1969, protesting at meetings, The Diamondback referred to its actions as “harassment” and “disruptions.” Later, it published a front-page story headlined “Whites protest BSU racism; ask to join.”

For another example, look to May 1970, when authorities shot and killed students at two different American universities. One shooting occurred at the primarily white Kent State University in Ohio — the other at the historically black Jackson State College.

A search of “Kent State” in The Diamondback’s archives from the years 1970- 1979 yields more than 250 results. There are fewer than 50 references, meanwhile, to “Jackson State” in the same time frame. Many of them appear in articles primarily about the Kent State shootings.

‘The epitome of whiteness’

1990 was a turning point for both Prince George’s County and The Diamondback.

That year’s census revealed that — after decades of gentrification — enough of Washington, D.C.’s black residents had moved to the county to turn it majority-black for the first time.

And, for the first time in The Diamondback’s then-80 year history, a black man had been selected as editor in chief: Ivan Penn, who grew up in Southeast D.C.

Penn, who now works at The New York Times, said many of his peers questioned his decision to work for the paper, often accusing him of betraying his black identity. After a series of complaints from activists over editorial decisions, Penn sat down with the Black Student Union.

At the center of a room, in front of a circle of black students — some of whom were his colleagues on the school’s gospel choir — he got an earful.

“Their question was, ‘Why are you going to work for the white newspaper?’” Penn said.

Bert Williams, a 1996 graduate and current co-president of the university’s black alumni group, said he read the paper every day. But he didn’t always feel satisfied with its coverage.

“People probably didn’t feel that we were getting the same platform for a major issue in the black community that some other stories or some other issues were getting,” he said.

When Corey Dade — who transferred to this university from a historically black college in Louisiana in the early 1990s — worked for The Diamondback, he was met with a predominantly white staff.

“It was the epitome of whiteness,” Dade said. “Plenty of them did have some personal experience with people of color, but they didn’t know how to translate that into their coverage.”

So, Dade said, when those white reporters wrote stories criticizing the universities’ black fraternities, for example — or stories that misspelled Frederick Douglass’ name and mistakenly identified W.E.B. DuBois’ book The Souls of Black Folk as “Sales of the Black Folk” — it only reinforced to black students that The Diamondback didn’t care.

“If you relied on The Diamondback to tell the story of the non-white student experience of Maryland, you would think there wasn’t a non-white student experience at Maryland,” Dade said. “It almost never existed. And when it did exist, it was problematic.”

Next pages

It had been more than 20 years since black students stole issues of the newspaper when Maya Dawit felt compelled to sit down at her computer and write a letter that began: “Dear Kyle.”

Days before, The Diamondback had published a column online headlined “The problem with today’s race war.” Kyle was the column’s author, and he’d crafted an argument against the Black Lives Matter movement that was reliant on false claims and faced intense backlash from the campus community in July 2016.

The hashtag #DearKyle gained traction on Twitter. Though The Diamondback’s then-editor in chief issued a statement recognizing that the column should not have been published, it had — by that point — worsened the paper’s already-fraught relationship with minority students.

“When people talked about The Diamondback, there was this idea: It’s very institutionalized. If you’re in it, you’re in it. And if you’re not, it’s hard to find your place. So then it’s really hard to diversify the stories that come out of there,” Dawit said.

Journalism is the first draft of history. Over the course of The Diamondback’s 110 years in print, we often got that draft wrong. Those failures, though they vary in scope, are as evident in the case of #DearKyle as they are in the pages of a 1940s newspaper that saw fit to advertise minstrel performances. This isn’t an all-encompassing look at our shortcomings, but we hope it’s a start.

From Monday on, what was the result of an act of protest in 1993 will become a stark reality: This paper will forever be absent from campus newsstands.

But the remnants of our ugly history — as a university, and as a publication — will remain, and we must reckon with it.