By Christine Condon, Lyna Bentahar and Eric Neugeboren

Staff writers

If you look at the first page of the 1970 University of Maryland M Book — a welcome guide for freshmen — you may not notice anything strange. At least not at first.

But if you look a little closer, and then turn the page on its side, you’ll see what the maze of lines and blocks truly spells out: “Fuck Elkins.”

Wilson Elkins himself, then president of the university, graces the very next page with a message for the class of 1974, blissfully unaware.

That year’s M Book was confiscated, said Susan Gainen, its editor and a Diamondback staffer who eventually became managing editor. Nowadays, that moment is considered part of the story of the rift between campus publications and the administration that eventually led to The Diamondback’s financial independence from the University of Maryland.

And after the spate of campus protests during the Vietnam War, and controversial editions of the campus features magazine — Argus — the connection between student journalists and their administrators became even more “un-tenable,” former Diamondback staffers said. Soon enough, an independent board was formed to oversee these publications.

“This was all about freedom of expression and freedom of the press, and our ability to print what was going on every day,” said Bob Mondello, a movie and theatre critic for The Diamondback in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. “Frequently, the administration and the student body were very much at odds about that.”

Before its independence, The Diamondback received some funds from the Student Government Association. But the paper was already a lucrative business, fueled by advertisements in its daily print editions. In the years since, the circulation of the print newspaper — and advertising revenue — has dwindled. But The Diamondback still supports itself, continuing a legacy of fierce criticism and truth-telling.

Covering a campus in chaos: The Vietnam War

Diamondback reporter and eventual editor in chief Chad Neighbor still remembers the day in May of 1970 when the campus protests broke out, shortly after President Richard Nixon announced the U.S. invasion of Cambodia.

He and sports editor Jerry Goldberg had been playing tennis on campus. Walking back home, they saw the crowds.

“It was like a scene from a film. There were 10,000 people down there,” Neighbor said. “We just looked at it and grabbed our notepads.”

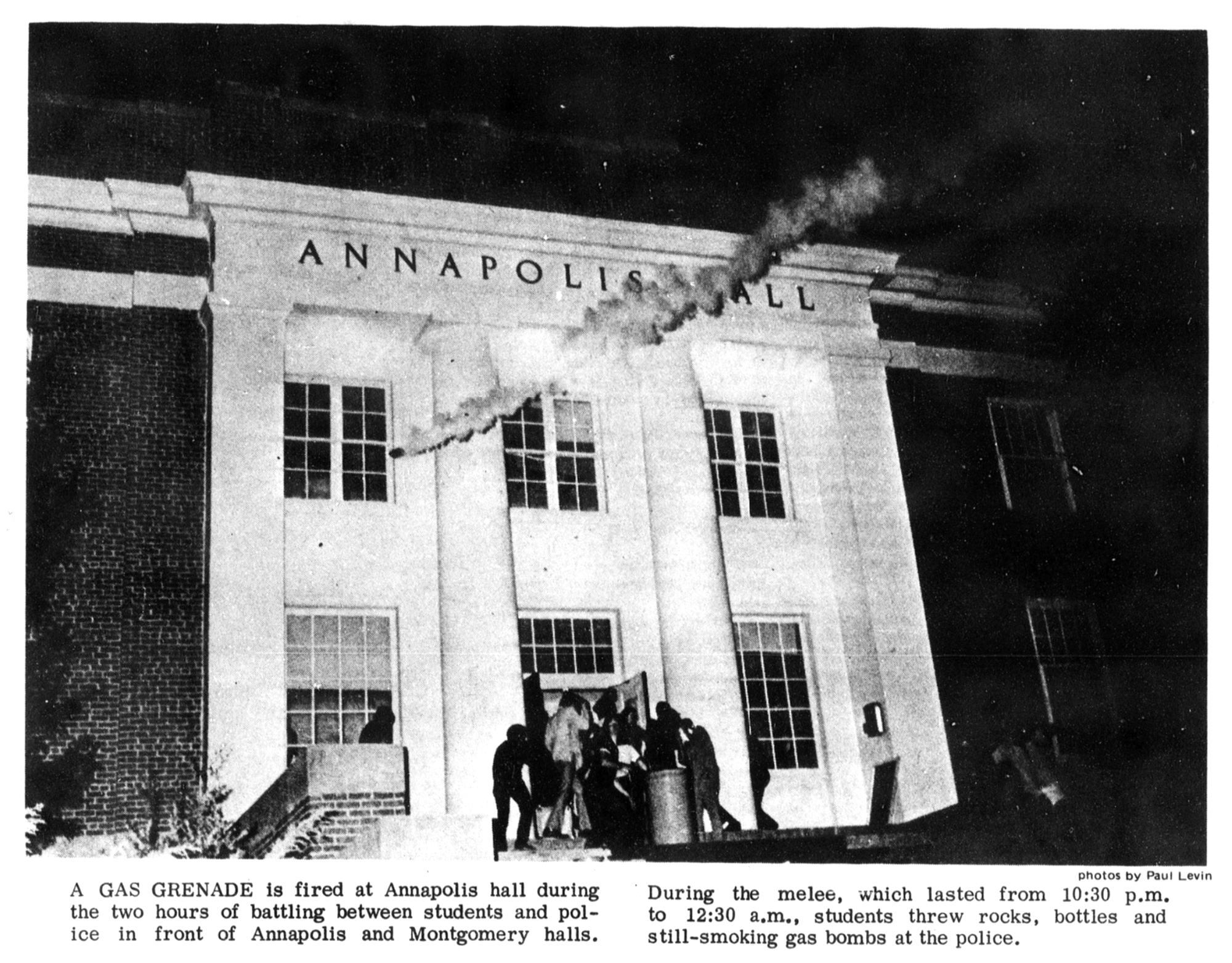

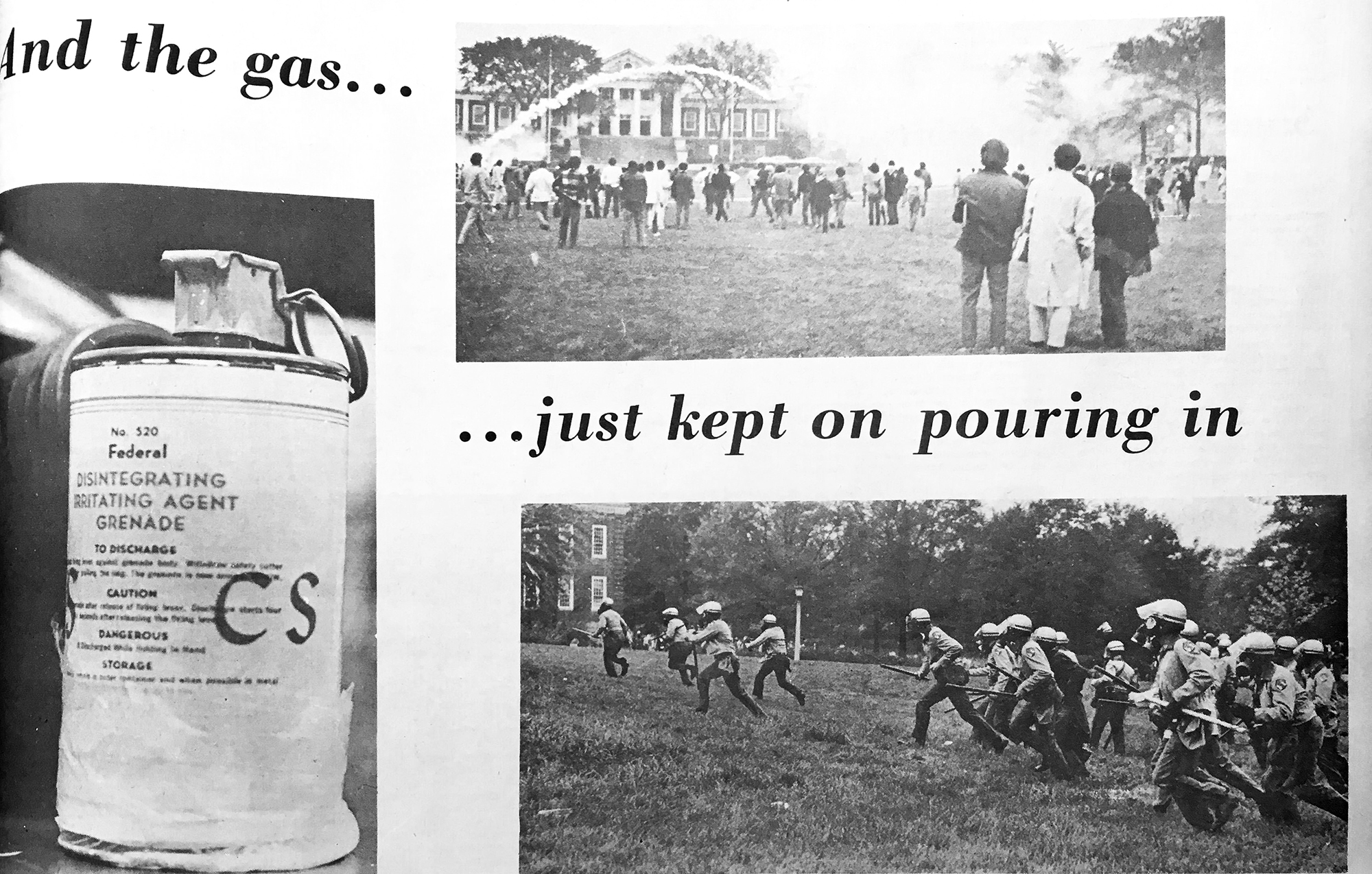

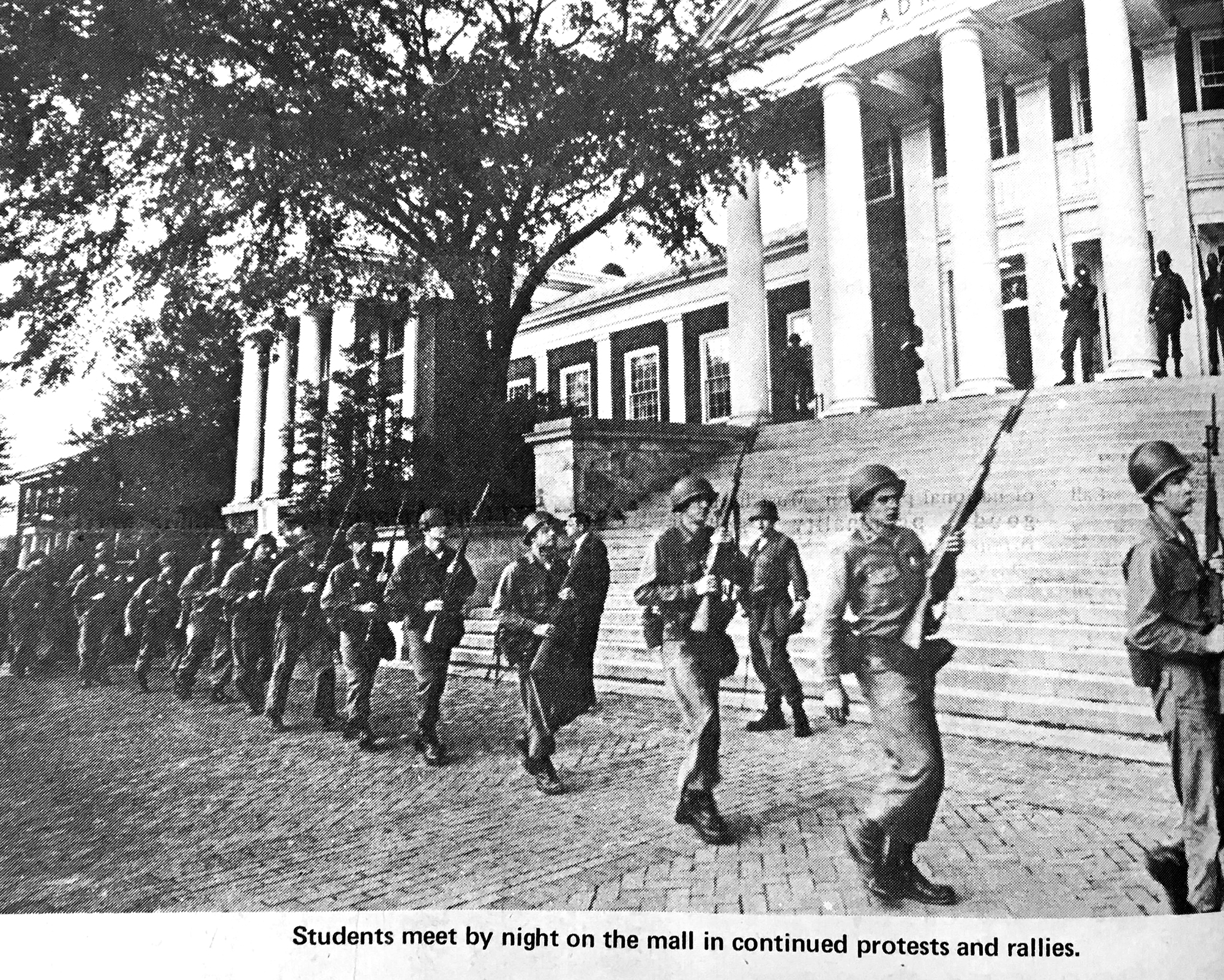

Student demonstrators managed to block Route 1 and even ransack the Reckord Armory — the headquarters of the university’s ROTC program. And the police and National Guard marched in, tear gas in hand.

The gas, which causes intense eye and respiratory pain, started to become a fixture of the reporting experience at this university in 1970.

“Honestly, it was sort of a rite of passage,” Gainen said.

Tension on the campus had already been high. Earlier that semester, more than 80 students were arrested during a sit-in at the Skinner Building in support of two philosophy professors who had been denied tenure.

“It was just a tinderbox,” Neighbor said. “All you needed was a match.”

The protests continued further into May, exacerbated by the killing of four students demonstrating against the Vietnam War at Kent State University by members of the Ohio National Guard.

And, at times, The Diamondback published critical coverage of the law enforcement officers attempting to disrupt the rioting. On May 5, the paper published an editorial titled “Gas attack on innocents incomprehensible” on its front page. And on May 6, it published images of tear gas alongside the message: “And the gas just kept on pouring in.”

Some readers didn’t take kindly to the paper’s coverage of the campus unrest.

“Taxpayers would say, ‘Hey, this is a communist publication,’” said Michael Fribush, who was the general manager for Maryland Media Inc., the company that manages The Diamondback, for over 40 years.

For Neighbor, though, the most memorable moment from that era didn’t come during a protest at all. Walking home from the newsroom one night, shortly before the campus curfew, he was arrested by National Guardsmen. When Neighbor saw the guardsmen approaching that night, he hid behind a bush. But they spotted him, and soon enough, he was handcuffed aboard a bus headed for the Hyattsville jail.

Naturally, Diamondback editors bailed him out.

Many Diamondback journalists from this era consider themselves lucky — to have witnessed history unfold on campus, messy as ever, and to have forged careers in journal-ism covering a student body torn asunder by a bloody foreign war.

“It’s a great crucible for journalists, because you just don’t get better experience than that,” Neighbor said. “The people from that era still get together. We have an annual reunion at Ledo’s and reminisce.”

And every day, there was a newspaper to put out.

“The Diamondback was absolutely the center of the universe for Maryland,” Fribush said. “Everybody picked up a paper … They were gone at the end of the day.”

Back then, editors would drive all the way to a facility in Silver Spring to arrange the type for printing, Fribush said. It was no wonder, then, that class often fell by the wayside.

“I was taking this business class, and I missed the midterm, I missed the makeup for the midterm, and I almost missed the makeup for the makeup for the midterm, because I was too busy being a student journalist,” Gainen said.

Argus fights censorship

Before and after the protests in 1970, Argus magazine goaded administrators with raunchy and politically powerful editions, paving the way for an independent board that would manage student publications.

In December of 1969, Argus tried to place an image of a burning American flag on its cover, but officials refused to print the magazine until the photo was removed. Eventually, the magazine would be printed with the word “censored” across its cover.

Argus ultimately sued Elkins for censorship with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union — and won. A federal district court ruled that the university couldn’t censor similar content in the future.

In 1970, the magazine promoted a creative pornography contest, a headline designed to incite the university to block it.

“We thought even using the name pornography, with nothing behind it other than saying this is a pornography issue, would be enough to get it banned,” said Dave Bourdon, former Argus editor in chief.

Argus would continue a movement of what then-managing editor Alan Lewis called “disruptive political theater.”

Meanwhile, there was progress being made toward establishing an outside publisher. But in a proposed makeup of the publisher’s board, only two student editors would have held seats, which prompted backlash. In an April 1971 editorial, The Diamondback wrote “the proposed board of directors is entirely, unequivocally unacceptable.”

Eventually, campus publications — which included the Black Explosion and the Terrapin Yearbook, in addition to Argus and The Diamondback — accepted a newly proposed makeup of the corporation, and in September 1971, Maryland Media Inc. was established.

The paper had officially cut ties with the university.

In the months that followed, the paper forged ahead, holding the university’s administration accountable in new ways. In an editorial published in March 1972 titled “What is the administration hiding?” the paper published faculty and staff salaries for the first time.

The process was not conflict-free, former staff member Sandra Fleishman said. Before publication, a journalism department staffer tried to take copies of the salaries from reporters.

“There were people who felt like it was an invasion of privacy, and I think that the university was embarrassed to not know that we were going to do that,” Fleishman said.

The editors of the student publications under Maryland Media Inc. didn’t know how independence would turn out in the long run. But, to this day, the paper remains financially separate from the university it covers — even as the print newspaper business becomes less profitable.

“The Diamondback did become the real newspaper it needed to be,” Lewis said.