Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

I will not occupy any space in this last print edition of the newspaper that I most love to falsely claim that much of the work we once did there mattered remotely, or that the stuff we wrote is timeless prose, or that we were on any given night princes and princesses of journalism.

Fact is, the years that I spent as a Diamondback writer and editor were an apprenticeship, and on a few notable occasions, a pratfall. As an independent, student-run newspaper, we had notable standards, and often, we kept to them. There were some fine moments. The Student Union ballroom burned in a late-night fire. We were able to strip it across the front page. The chancellor resigned and we had double-truck coverage of his career ready the next day. We went to Baltimore and wrote a feature story that actually referenced a dildo that we described, in print, as being the size of “a healthy pine sapling.”

We did think it all mattered. You have to think so. Journalism is no fun at all unless you come to the newsroom every day and think it all matters. As has been said of all academia, the fights were so ruthless because the stakes were so small. Or so it seems in retrospect. The issues and the arguments and the headlines do not, for the most part, rise to the level of being the first draft of any history that much matters to anyone nearly forty years later. Tuition hikes, campus desegregation goals, student government misallocations, dormitory vandalism – all of it now seems dry grist for a small-market mill.

And yet, my god, we did care about doing it right.

What The Diamondback delivered to anyone whoever walked up the main dining hall stairs, veered into its doors, sat down and began to type copy was this: A simple and abiding belief in an unaligned and apolitical craft. We genuinely didn’t give a shit if the University of Maryland excelled or collapsed, or if Hell cracked a gaping maw under Route 1 and swallowed College Park whole. We only cared that we could report as much in some coherent form and maybe get a photog down there so there would be art on the front page.

Once, covering a Board of Regents meeting, I came up with an ethical test that no hack regent could pass and in doing so, I saw the simple opportunity for a story. It seems a new member of the regents was one of the largest construction magnates in the Washington area. Would the regents put him on the university board’s building committee and risk the obvious conflicts every time that panel voted on a capital project? Or would they embrace an ethical moment and assign him to other duties and ask that he recuse himself on all matters involving university building projects?

I asked the Board of Regents Chairman.

“What would you do?” Peter O’Malley asked, turning the question back on me.

“Me? I don’t care. I get to write the story either way.”

The man looked at me with real contempt.

“That,” he said, “is incredibly cynical.”

“Thank you,” I replied in earnest.

Mind you, these were the years after Watergate, when the journalism school was flush with acolytes, and when American institutions were being doubted and interrogated in every possible way. I do believe that many of us in that tiny newsroom were preparing ourselves for a career in which permanent doubt was to be the operant ethic. The world could no longer be relied on to provide proper outcomes in the wake of proper journalism. At best, you could find a place to stand upright on the notion that you got as much right in your story as you possibly could. The world might not get fixed, but your third graf could be made better if you reworked that lumpy middle sentence.

About a year after I finished my three and a half years at the student newspaper, when I was stringing for a newspaper in Baltimore, covering the campus and the Maryland suburbs and trying to write my way onto the metro staff, I caught the university’s men’s basketball coach in a vile little scandal.

In this era of #MeToo and #TimesUp, Lefty Driesell would have been immediately sacked for throwing a tantrum after a campus judicial board had disciplined one of his players for a sexual impropriety, and for calling the reporting victim repeatedly and screaming at her over the phone that if she didn’t withdraw the complaint her reputation would be destroyed on campus, and for doing so with a university administrator listening on a phone extension in the undergraduate’s dorm room. A scenario even half as ugly would destroy any practicing sonofabitch today. But no, back in 1983, boys would be boys and after a long, quiet investigation and then a public wristslap, the University of Maryland gave Driesell a five-year contract extension and more money. From that moment forward, I knew my ethos:

The world will be the world. Corruptions may abide. Deceits may prevail. Reform may descend to farce. And the response to the best journalism might be for someone to rush into the breach and pass the worst law. All of that may be true, but in the end, I still get to come to the campfire and tell you a story. And if the story is true, if I know most of what I need to know and if I write it well enough, then, OK, the rest of you motherfuckers can never say you didn’t know. I’ll take that much and run with it.

Forty years after I walked into The Diamondback, that’s the only ethos that still stands. And while nothing much that I wrote or reported or edited in the pages of the campus daily stands up to time in any way, the matter of publishing an independent edition of a newspaper every day and giving some weight to getting shit right, or even written a little more cleanly, was maybe the first real opportunity for a bratty, argumentative, suburban wiseass to grow up. Above all, I have to credit The Diamondback fully for this.

When I went to Baltimore to be a newspaperman, I wasn’t going to be easily rattled or flattered or co-opted by any other cause than clean copy. In short, I was already enough of a sonofabitch to do the job. The Diamondback gave me that and in retrospect it was the greatest gift.

That there will be no more newsprint makes me wince, but I am a sucker for the worst kind of nostalgia. The fact is, the institution of the student-run daily in College Park, Maryland still evidences itself online. The premise of undergraduate reporters and editors wrestling with words and quotes and arguments is still served. A rose by any other name.

And to those now in that newsroom, I can offer only one other retrospective notion and it’s this: If you spend a lifetime in journalism, you may have some stories that matter more, you may do work that is of greater importance, and you may serve some greater societal purpose. But you will never have as much fun as when you and the other sleep-deprived and beerstained wonders around you published your own damn newspaper.

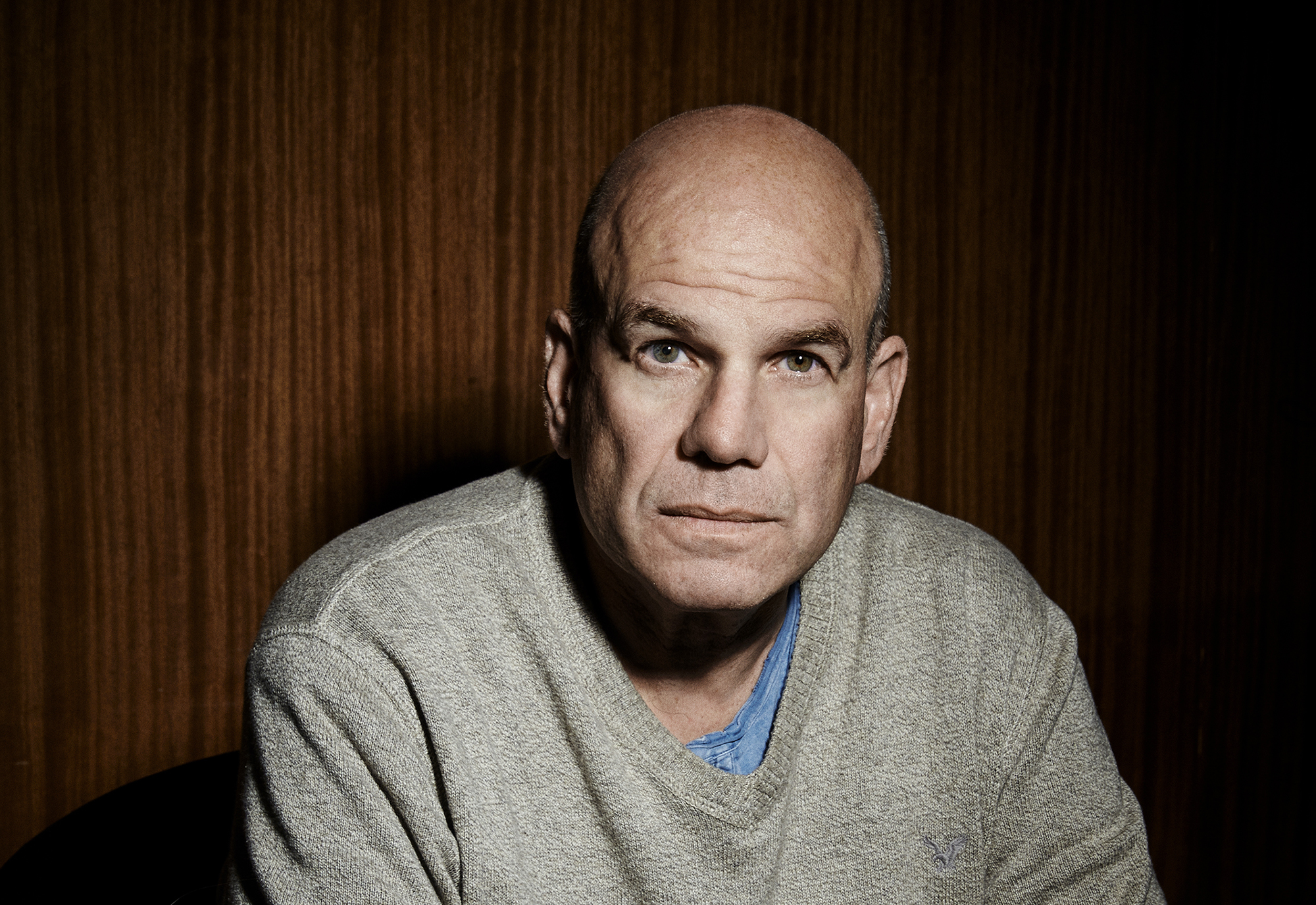

David Simon worked at The Diamondback from 1979 to 1982 and was the editor in chief for the 1981-82 academic year. Simon is now a writer and producer, well-known for creating ‘TheWire’ television series. He has won two Emmys, and previously reported for The Baltimore Sun.