For some, the steady shuffle of life after college has left the years spent in that slightly dingy room above the South Campus Dining Hall a bit smeared around the edges.

But how could they forget the night the cops showed up at a newsroom party after a couple of people decided to launch an old typewriter out a window? What about election night in 1968, when a hard-pressed editor coming up against a deadline OK’d the next day’s print paper to announce — incorrectly — that it looked as if the next president could be decided by the House of Representatives?

They’re eager to recount the D.P. Dough feasts, the impromptu rooftop concerts, the couch of questionable origins that was probably flecked with questionable substances. And they recall the screw-ups. The times they let their readers down.

Most of all, though, the alumni of The Diamondback remember what it was like to have a scrappy student newspaper utterly consume their lives — the sort of exuberant, sometimes delirious level of devotion required to capture life at the University of Maryland.

Things will be a bit different at the paper after this week. After years of watching its print circulation steadily drop, The Diamondback will become an online-only publication.

Even journalists are prone to sentimentality when endings are in sight. So, as the weeks before the final print edition ticked by, former Diamondbackers revisited their years at the paper — the stories that shaped campus, the experiences that shaped their lives and how things will change moving forward.

“It’s just a time in my life that I’m gonna remember forever,” said Mike King, the paper’s editor in chief from 2013 to 2014. “You know, the specific details of the technical things like working with the copy editing software, calling the printing press and that kind of stuff — that’s part of it. But the main part is just the memories and learning and growing and meeting people.”

“And I think it’s a really beautiful thing.”

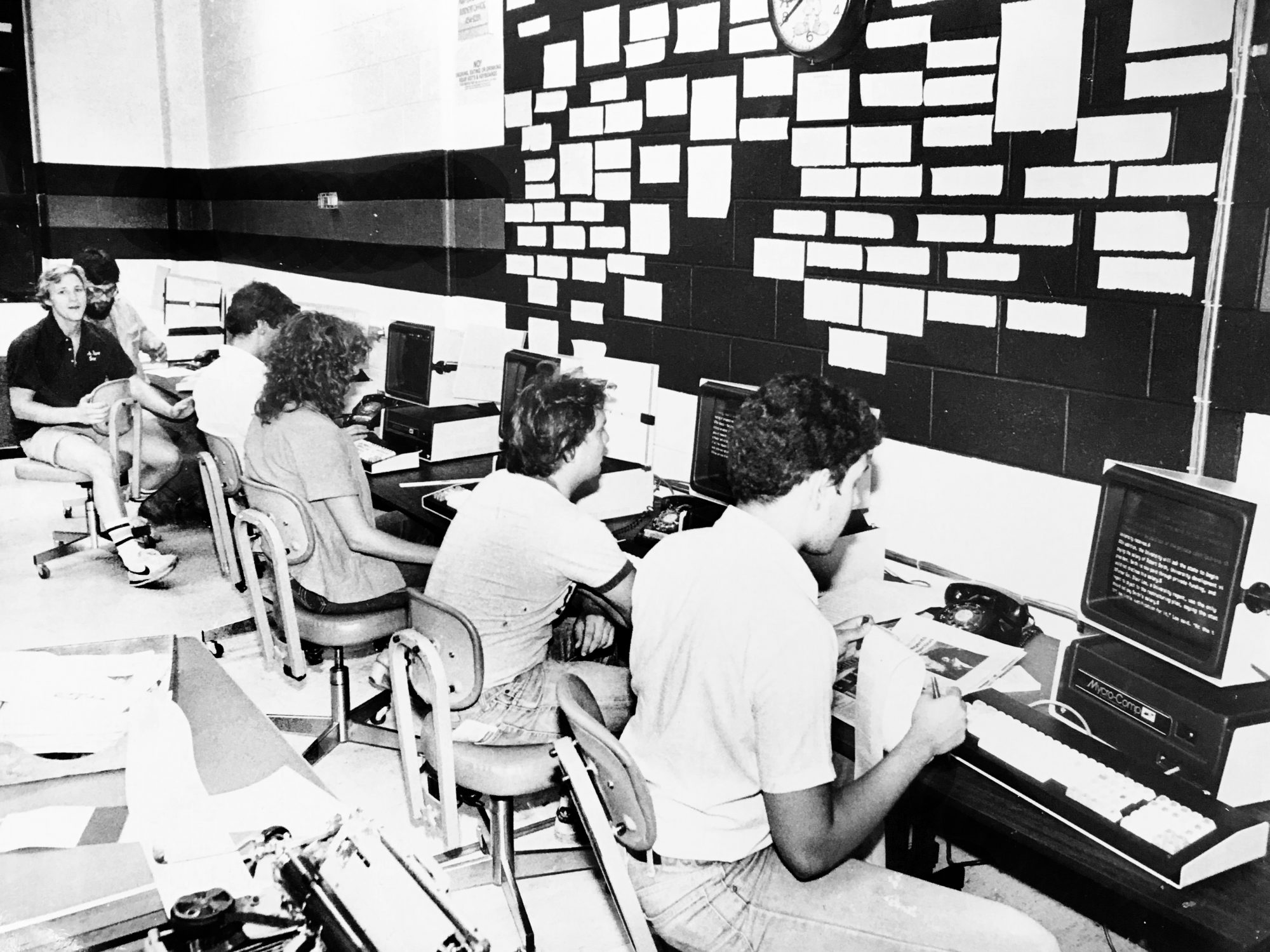

Diamondback staffers work in the newsroom in the early 1980s (Diamondback Archives)

*****

Jerry Ceppos remembers how heavily the Vietnam War hung over the campus in the 1960s. Even students who weren’t facing the draft were scared for their brothers, their boyfriends.

And just as the war consumed the thoughts of everyone on campus, Ceppos said it seemed to consume The Diamondback’s coverage.

“It was a shared experience in every sense of the word,” said Ceppos, who was editor in chief from 1967 to 1968. “So it was a story that affected all of us more than most stories.”

In the end, these kinds of stories are the ones that reporters and editors remember: the ones that tore at the fabric of campus life and broke the heart of the community. They remember the ones they reported even as grief or fear spun through their own lives and the ones that shocked administrators into action.

But they remember moments of softness, too.

Maria Stainer describes her favorite memory from the many years she spent at The Diamondback as the time she helped cover a poetry reading from Gwendolyn Brooks. At first, she remembered, the audience was quiet as the small woman stepped up to the podium.

Then, like a “Sun god” busting into the room, Terps basketball superstar Len Bias strolled in, clutching a bouquet of pink carnations and daisies and wearing a navy blue suit. He presented the flowers to Brooks and gave her a kiss on the cheek — prompting the crowd to jump to their feet, yelling and cheering. Brooks, Stainer remembers, smiled ear-to-ear.

Stainer was still working at the paper when Bias died due to a cocaine overdose in the summer of 1986, just two days after he’d been drafted by the Boston Celtics.

Bias’s funeral service was the last thing Matt Wascavage ever photographed for The Diamondback. It was a surreal experience, said Wascavage, who worked at the paper from 1982 to 1986.

“It’s sort of one of the times that, [when] I look back at The Diamondback, that I remember pretty vividly,” he said. “I remember being up on the top of the hill of the chapel, where we were, standing across the street. Just being there.”

Another moment burned into Wascavage’s memory is the Challenger space shuttle explosion in January 1986, killing all seven crew members. One of them, Judith Resnik, earned her doctoral degree at this university’s engineering school.

Wascavage had photographed her once, he remembered. Since the science reporter had been late to the interview, Wascavage had spent some time alone with the astronaut, snapping pictures and listening to her stories.

On that day in January, Wascavage remembers watching the explosion on his television at home and taking in what had happened. Then, he pulled his things together and headed over to the newsroom.

When Jaclyn Borowski thinks back to her years at The Diamondback, though, she doesn’t recall a time of sadness — instead, she remembers unbridled joy.

It was Nov. 4, 2008, the night Barack Obama was elected president. A horde of students charged through campus, shouting and cheering. Borowski doesn’t know when they gathered exactly or where they came from.

“I think students were just so happy. It was such a big moment that they just wanted to celebrate with other people,” said Borowski, who worked at the paper from 2007 to 2011. “It seemed like they just had a bunch of energy and they didn’t know what to do with it.”

They wound up sending the paper late that night, Borowski, said. Way past deadline.

But when all was said and done, another editor brought Borowski home. As they drove back to her dorm, dawn began to break.

*****

In the beginning, Mike King wasn’t exactly Laura Blasey’s favorite person at The Diamondback. He was just some weird, bald guy who liked to coordinate newsroom D.P. Dough orders.

Then, in the fall of 2012, she got him for a Secret Santa gift exchange. She bought him a D.P. Dough gift card and a box of Cheez-Its — and he freaked out. Hugging the Cheez-Its to his chest, King shouted out, “My wife!”

Blasey didn’t find his reaction very funny.

“I was like, ‘Are you joking?’” she said. “I was just so put off by that.”

Throughout the following year, though — when King was editor in chief and Blasey was news editor — they gradually became close friends. Then, more than friends.

And in less than three months, they’ll be getting married.

The Diamondback has produced its fair share of couples. But the newsroom, with its grimy floor and temperamental thermostat, has led to lifelong friendships, too.

Debra Moffitt remembers the newsroom as a haven of acceptance. The campus is big, she said, and often, you’re judged based on how you look — especially if you’re a woman. That wasn’t true at The Diamondback.

“It was a place that kind of valued your mind and your intellect,” said Moffit, who worked at the paper from 1987 to 1989. “And you could be a quirky person there, and there was almost no downside.”

From Stainer’s first day at the paper, that was the impression she got, too. She had just transferred to this university’s journalism school after spending almost four years studying biology at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County. The second she walked into the newsroom, she remembers, “it was like, put your coat down — we have work for you.”

Students gather for the 1989 Diamondback yearbook picture (University Archives)

More than 30 years later, Stainer still thinks of the people she met that day as family. They laughed together, drank together, crashed on each other’s couches. One night, as they were nosing around South Campus Dining Hall, they found their way onto the roof. It became their hang-out spot, Stainer remembers.

“[The newsroom was] where we studied, that’s where we did homework, that’s where we socialized,” Stainer said. “That was sort of a second home.”

Dilshad Ali, who worked at The Diamondback from 1993 to 1996, echoed Stainer. Throughout college, she commuted from Gaithersburg. She didn’t have a dorm to go back to during the day, so the newsroom became her pitstop — where she went to work between classes, to make phone calls, to nap on that “god-awful sofa.”

More than anything, though, Ali remembers how much everyone learned from one another and how seriously they took their jobs. For some, she said, it was almost like they weren’t at school to get a degree, but to work at The Diamondback.

“It wasn’t like this thing you just did to put on your resume, or to get some work experience,” she said. “We cared. We cared about the newspaper, we cared about the university and the community, we cared about reporting the truth and the news. We cared about doing a good job.”

*****

In the 1960s, Ira Allen got to be a bit famous around campus after he started writing columns for The Diamondback that skewed on the liberal side. Some students didn’t take too kindly to his opinions — they called him a communist, a radical, “every name in the book.”

But he didn’t really mind. In fact, he enjoyed it. It taught him how powerful the press was — a power that was underlined by its tangible product.

“It was in print, you could hold it, you could read it,” he said. “Even if it was dumped in a hallway or under a desk in a class, it kind of had a life.”

The announcement in September that The Diamondback would move entirely online came as a blow to those who fondly recall the days when it seemed like everyone had a copy of the paper hidden in their notes during class — and not so much to those who remember walking past newsstands that never seemed to get depleted.

But for most, it wasn’t a surprise. The agreement was preceded by the decision to cut the Friday edition in 2013, and in 2015, to print only once a week.

Blasey was editor in chief when the latter decision came down. She remembers the frustration that led up to it — of needing new camera or computer equipment and realizing there just wasn’t enough money.

She also recalls the rude awakening she received when a science professor pulled out a huge stack of Diamondback issues from the storage closet and spread them over the tables before beginning some messy experiment.

“I remember the paper that was on my table had a story that I had written from several years ago,” she said, laughing. “Just knowing that there wasn’t really a demand for the print product anymore, and a lot of that demand that we were still seeing seemed to be from science professors picking up a stack of newspapers for their lab class.”

When the cuts were announced, Blasey said, she didn’t remember hearing a lot of opposition from reporters or editors. Instead, much of the pushback came from Diamondback alumni.

“It feels like this very emotional, personal experience,” she said. “Sometimes it’s hard to separate the financial reality from all of these nice memories that you have. And I think that’s sort of where people were coming from — they were sort of in mourning for this paper that they had in their head.”

Diamondback editors pose for a 2015 photo in the newsroom. (Courtesy of Laura Blasey)

But this time around, even folks who were raised by a Diamondback that churned out a print edition every weeknight have been understanding of the move. Most have even been supportive.

Ceppos called it the right decision, especially for “a market full of young people who are just not picking up print newspapers anymore.” Ali called it an “inevitable” change, falling right in step with the changing face of journalism. Stainer was optimistic, too.

“It’s not the delivery system that makes it important,” Stainer said. “It’s not the plate you [use] to serve the spaghetti. It’s how good the spaghetti is.”

*****

Reader, in this topsy-turvy industry that seems to be in a constant state of change, we can’t say a whole lot for certain. But we can promise you one thing: Although we will undoubtedly come up short sometimes, we will keep on trying our damndest to do right by you.

And together, my good friends, we will make some incredible spaghetti.