A leather-bound book lies in state, resting in a trunk beneath the spattering of diplomas and family photos that dot the walls of Glenn Dickinson’s California home. It’s full of newspapers and was a gift, a relic from his time at The Diamondback, where he served as editor in chief from 1986 to 1987.

Once opened, though, the book reveals more — the wounds of a community left reeling after the loss of one of its own, Maryland men’s basketball star Len Bias.

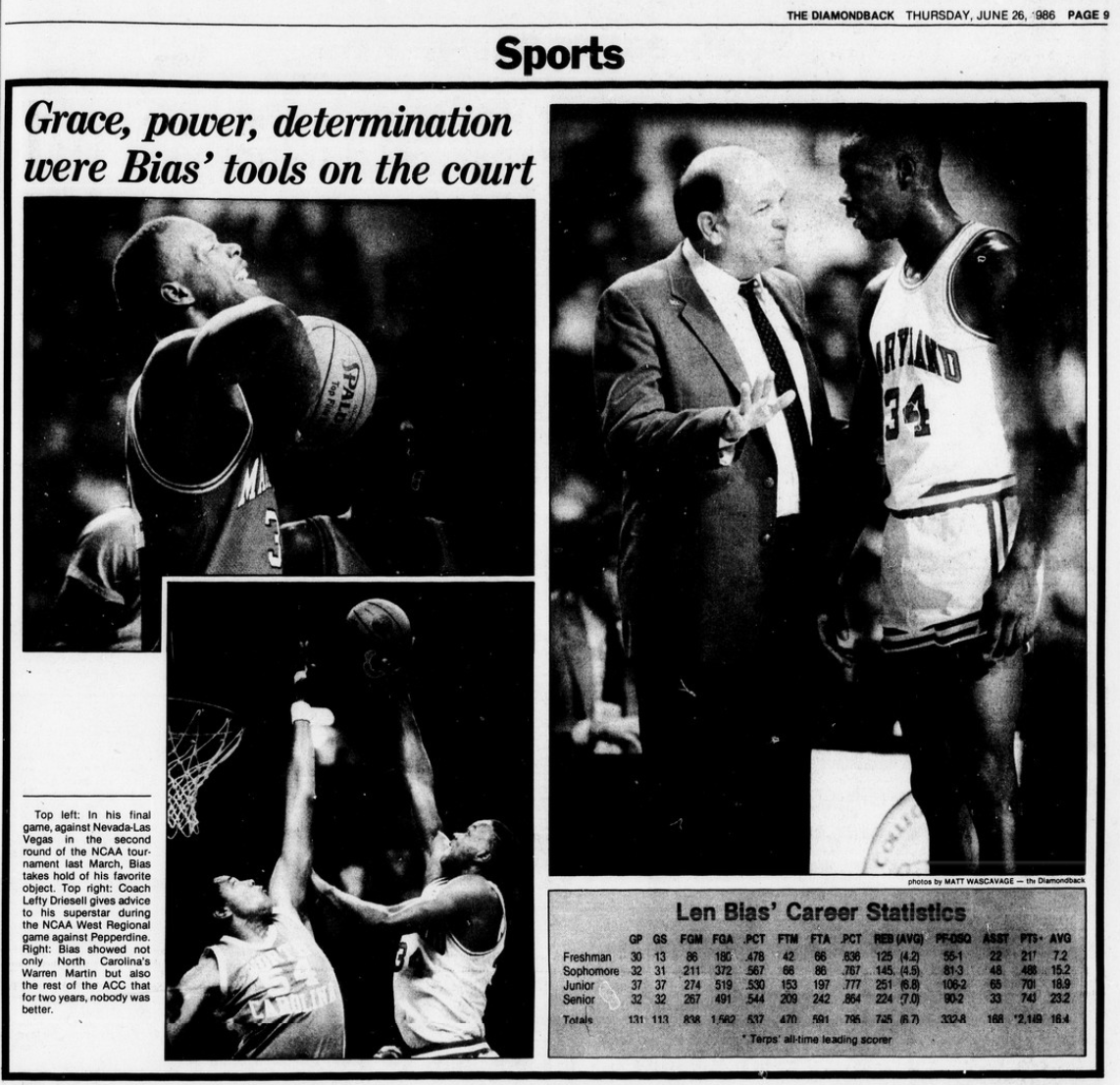

On June 19, it will be 34 years since Bias collapsed in Washington Hall. He would be pronounced dead hours later, a cocaine overdose cutting his life short at 22. Just two days earlier, the Boston Celtics had selected him with the second overall pick in the 1986 NBA Draft.

During the summer, The Diamondback would temporarily become a weekly publication, prompting a few reporters to take summer classes to stay close to the newsroom. Dickinson, whose term as editor in chief began just a week before, vividly remembers the moment he found out.

“I walked into the newsroom, and [sports editor] David Grening is there,” Dickinson said. “He’s standing at the printer and staring down printing something out. And I say ‘Dave, what’s up?’ And he looks up to me with this dead look on his face and he said ‘Len Bias died last night.’ … I remember thinking my whole summer just turned upside down.”

Bias’s death brought an onslaught of turmoil, not just for the University of Maryland’s athletic department and administration, but for the student newspaper, too — idealistic young writers, editors and photographers instantly thrust into the world of professional journalism.

Yet through it all — the countless nights when reporters hunched over a clunky Teletype machine to await details of potential sanctions, the press conferences where Dickinson was surrounded by people who had decades more reporting experience than him — The Diamondback staff persisted, fueled by a sense of camaraderie that extended well beyond the newsroom.

“It draws you together,” Dickinson said. “When you go through an ordeal with people, you develop a closeness.”

The Diamondback’s tight-knit nature started slowly, though. With national publications descending upon College Park, veteran journalists’ voices dominated press conferences and interviews. And for amateurs such as Grening, the stress of the competition was difficult to escape.

“[The Washington Post’s] Sally Jenkins, I remember she was there like every day,” Grening said. “They have great sources — even though you’re a student at the school … I didn’t co-mingle with the basketball team and [didn’t] really [know] how to cultivate sources at that time.”

But as time went on and the scandal surrounding the athletic department and university administration intensified, The Diamondback’s group of young reporters found their footing, strengthened by a collaborative process that fortified relationships between its staff.

The news desk handled most of the coverage, a byproduct of the circumstances surrounding Bias’s death and the scale of the NCAA’s subsequent investigation. The sports desk served more of an advisory role, giving an athletic context to some of the upheaval.

“It was really the editors getting together and just determining [to] let the news reporters be the news reporters, and let the sports reporters help out,” Grening said.

It wasn’t always easy — the two desks often clashed over which direction to take a story, Dickinson said.

But the arrangement worked well for both parties in the end. Editors Neff Hudson and Janet Naylor earned plaudits from Dickinson for their investigative reporting and interviewing skills, while Grening and assistant sports editor Bob Mosier were able to immerse themselves in their beats. And as The Diamondback’s staff continued to report on the scandal — which would trigger the resignations of men’s basketball coach Lefty Driesell and athletic director Dick Dull — so grew their affinity for one another, best reflected on Friday and Saturday nights when reporters dropped their notepads and pencils in favor of beer cans and booze.

“We did develop a very serious camaraderie, and we would have parties, and we would hang out together,” Dickinson said. “Really great parties, actually — I remember some of them so vividly. A little wild, a little bit bohemian, but nobody broke any laws.”

What The Diamondback’s staff lacked in experience and clout, it made up for in solidarity. The newsroom served as a habitat for collaboration — and keggers, on occasion.

It was a togetherness that was calcified in the early days of the Bias saga, its reporters sitting at bulky computers for hours on end trying to find some sort of new angle that hadn’t been explored in the sea of national media attention that followed Bias’s death.

And it’s a togetherness that’s captured in the weathered book that rests in Dickinson’s trunk, tales of a group of young friends who fought for their seat at the table in the midst of tragedy.