By Gabrielle Lewis

For The Diamondback

John Holdren, the lead science and technology adviser for former President Barack Obama, believes technological progress is crucial to finding a solution to the climate crisis.

“The fact is that advances in technology are an important part of the solution,” Holdren said. “My own view is that the most demanding driver of energy technology innovation … is the need to reduce energy’s impact on the climate.”

Holdren, a Harvard professor, was the keynote speaker Tuesday for “Meeting the Energy-Climate Challenge: Science, Technology, and Policy at a Crossroads,” a lecture held at the University of Maryland’s Bioscience Research Building.

Holdren showed in a diagram that greenhouses gases contributing to climate change — carbon dioxide and methane — mostly come from fossil fuels, pinpointing the energy source as a major cause for global warming. If the world continues depending on fossil fuels, Holdren said, then the planet will reach a point of unmanageable climate change — and time is more imminent than many may think.

He discussed the need for more energy-technology innovation and cited several issues that need attention, such as improving electricity grids and efficient buildings and industrial processes, as well as the possibilities for the future of policy.

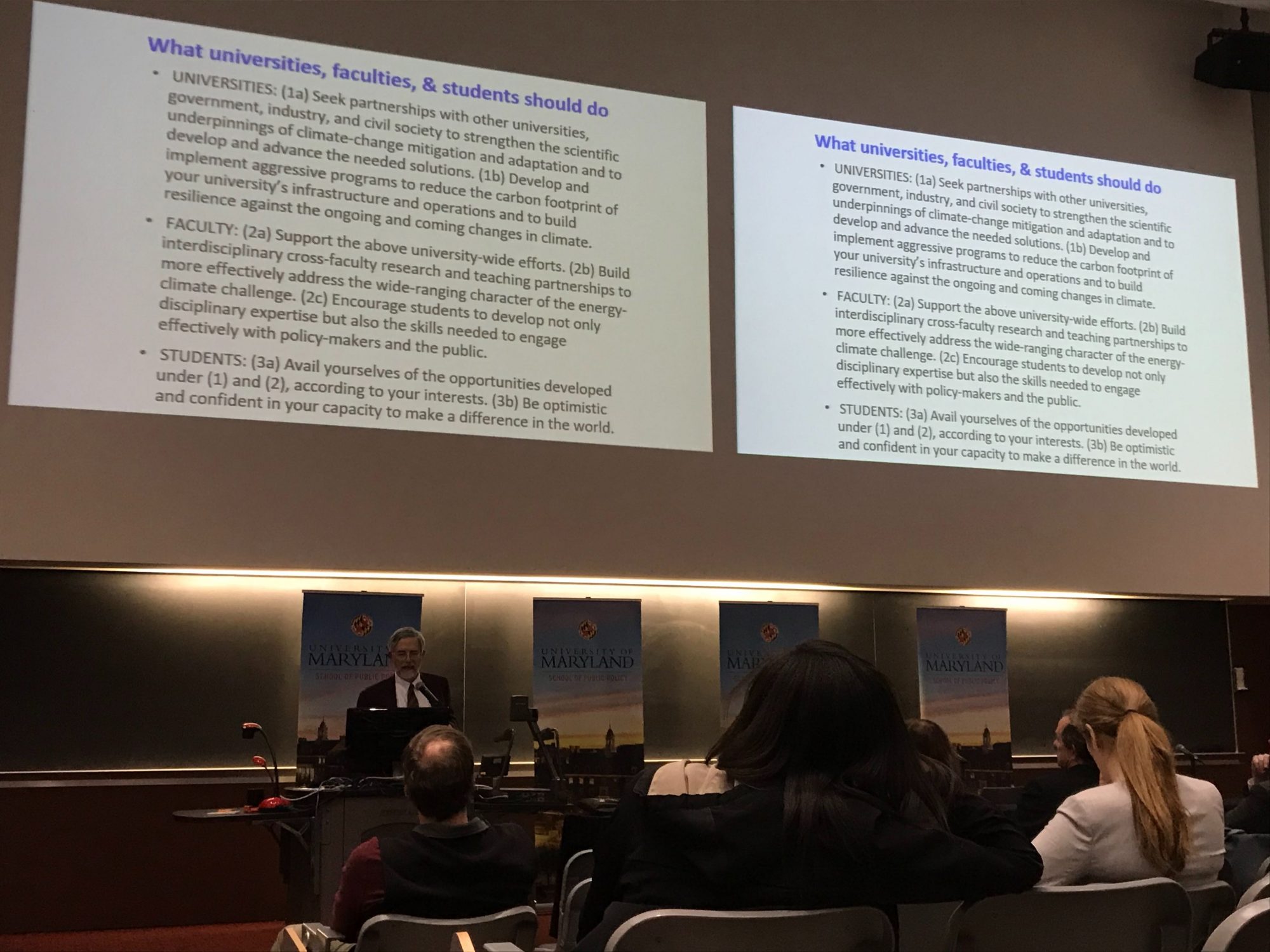

Specifically, he said a massive program of technological innovation on clean energy and energy efficiency needs to be made via collaborations between government entities, industries and universities.

“It’s a global problem,” Holdren said. “We got to solve it together.”

[Read more: UMD students developed technology to help cut down on returns in online clothes-shopping]

In terms of possible solutions to the issue on the whole, Holdren said three are available: mitigation, adaptation and suffering. The world is practicing a mix of the three, he said, but to minimize future suffering, a combination of mitigation and adaptation is needed.

“What we need is enough mitigation to avoid unmanageable climate change and enough adaptation to manage and avoid climate change,” Holdren said.

He provided examples for both mitigation practices, such as increasing reforestation and afforestation, and adaptation practices, such as preserving and enhancing “green infrastructure.”

Holdren also noted the remedial efforts against climate change that are in place. He counts the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement as triumphs in addition to environmental efforts by the Obama administration, such as measures to reduce emissions from power plans. In contrast, the Trump administration has withdrawn the U.S. from the Paris Agreement, rescinded Obama’s climate change executive orders and energy targets and cut funding to countries in need.

Simin Li, a junior computer science major, said Holdren’s comment about society’s three options for future solutions stood out to her. She said she feels media outlets talk more about mitigation efforts rather than adaptation efforts. However, she believes the event focused too much on government spending rather than on the consequences of climate change on individuals.

“I think if he had elaborated more on… per person versus per number,” Li said. “He said the sea level increase would be by three feet but not by how many people that the three feet would displace.”

[Read more: “The time is now”: Panelists discuss environmental, racial activism at climate change talk]

The event, hosted by the public policy school, consisted of a lecture by Holdren followed by a four-person panel discussion, which included Provost Mary Ann Rankin, graduate school Dean Steve Fetter and Fernando Miralles-Wilhelm, the chair of the university’s atmospheric and ocean sciences department.

Rosina Bierbaum, a research professor in this university’s public policy school and the panel discussion moderator, said that the public policy school had been trying to amplify this university’s science policy stature — and bringing Holdren to campus seemed like a clear way to boost student and faculty interest.

Benton Anthony, a junior public policy major, thought Holdren’s lecture effectively communicated the significance of the climate change crisis, the urgent need for solutions and the fact that climate change isn’t sequestered to one part of the planet.

“It’s the future of the world as we know it,” Anthony said. “We as a nation tend to say that America’s doing well, America’s doing poorly — but it’s a worldwide effort.”