Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

“A President is Born: Barbra Streisand sings Mike’s praises.”

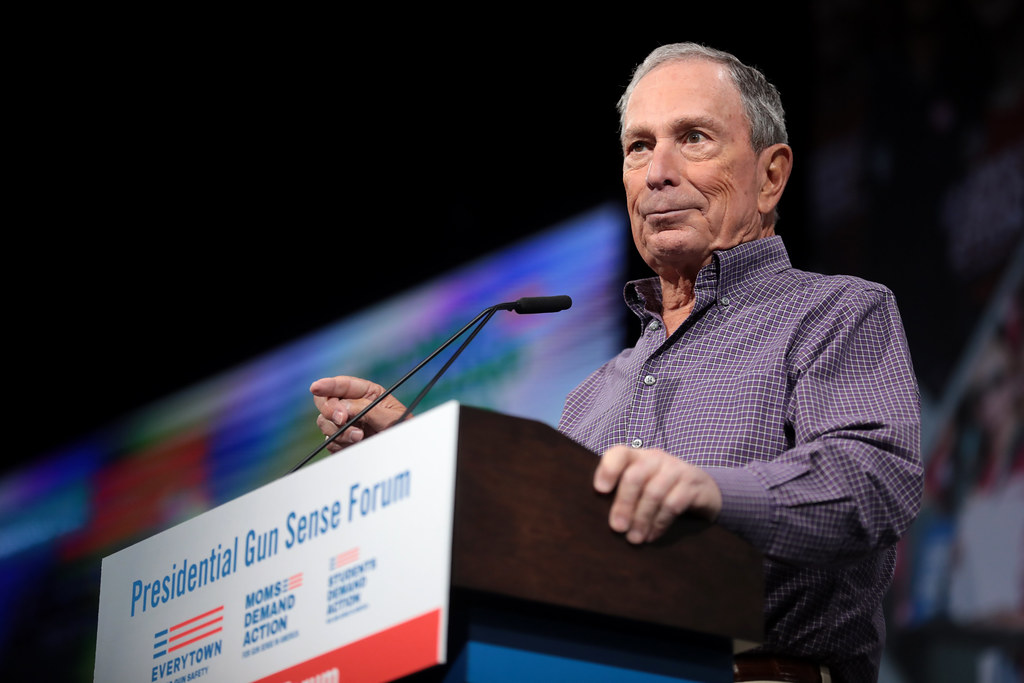

It’s a phrase I never thought I’d see posted once, let alone multiple times by different accounts. The tweets also included a bit.ly link to “check out [Streisand’s] tweet” in support of Michael Bloomberg’s presidential campaign. This strategy, coordinated by the Bloomberg campaign, uses temporary “deputy field organizers” who are paid $2,500 per month to push eerily similar text, links, hashtags and images in support of the campaign across Twitter, Facebook and Instagram.

Similarly, Bloomberg’s campaign came under scrutiny for its paid influencer ads in the form of memes on some of the most popular accounts on Instagram. It was organized by Meme 2020, a project that involved accounts with a collective reach of over 60 million followers. One meme read as a direct message from Bloomberg’s account: “Hello Juice Boys. Can you post an original meme to make me look cool for the upcoming Democratic primary?” All of the memes posted as of Feb. 13 included disclosures that they were sponsored posts, but it’s not the only way Bloomberg is using influencers to hype himself up — his campaign is also offering a fixed $150 to accounts with between 1,000 and 100,000 followers to “Show+Tell why Mike is the candidate who can change our country for the better.”

Regardless of what you think of the identical tweets and Instagram memes (I find them both pretty lame and innovative at the same time — awful content, but new ways to engage voters), they represent the latest method of digital astroturfing. Astroturfing is the faking of grassroots support to make it seem that the astroturfer has more real, on-the-ground support than there actually is. Bloomberg’s spending on digital, including paying for deputy field organizers and sponsored content (dubbed #sponcon for short), has amounted to $50 million from the start of his campaign in November to the end of January.

What’s most concerning about all this is Twitter and Facebook’s slow and narrow approach to combating this astroturfing. Aside from a cheap reference to the 1976 classic Streisand film A Star is Born, the tweets were in violation of Twitter’s “platform manipulation and spam” policy. The company suspended 70 accounts that have posted the Streisand tweet and other pro-Bloomberg posts — all identical across multiple accounts — many of which were only created in the past two months.

On the other hand, Facebook is considering ways to show that identical posts from those deputy field organizers are, in fact, coming from paid staffers. But the company, which owns Instagram, won’t include those memes from influencers in its interactive political advertising database on the basis that they fall under the platform’s policies on branded content, not “Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior.”

All this leaves more confusion than clarification and creates more work for the platforms than necessary. Taking things on a case-by-case basis, as Twitter is doing, seems awfully sluggish at a time when the Internet moves faster than ever. Facebook’s lack of “clearer guidance from regulators in this area” points to the Federal Election Commission, which hasn’t officially updated its rules on internet communication since 2006. The commission last proposed revisions in 2018, applying the same rules for disclaimers for paid political ads in traditional media to online ads.

Any official, legal rule changes affecting Twitter’s or Facebook’s policies on these kinds of digital astroturfing would take place after the presidential election in November, if at all. So, we’re left with Twitter’s and Facebook’s lackadaisical methods of determining where these identical posts and sponcon fall under existing policies, rather than more strictly enforcing those policies or creating new ones altogether.

Twitter’s decision that the Streisand tweet accounts and others like it fall under its platform manipulation and spam policy is good. It also indicates that its definition of platform manipulation and spam isn’t broad enough. “Coordinated activity, that attempts to artificially influence conversations through the use of multiple accounts, fake accounts, automation and/or scripting” doesn’t overtly include politics as a topic that ‘conversations’ often coalesce around on the platform.

Facebook is taking a step in the right direction by working on a policy to create more transparency around those kinds of posts by paid staffers, but its efforts in the name of clarity when it comes to paid relationships should extend further than actual employees and include sponcon and other branded content. Paying people to post memes seems like a pretty clear example of a paid relationship. It also seems to fall under a reasonable person’s definition of “coordinated inauthentic behavior,” so it’s unclear why it currently doesn’t fall under Facebook’s current policy, which only has six defined violations.

Presidents aren’t born — they’re made, and Twitter and Facebook could just help make the next one if they don’t work faster and think bigger when it comes to political candidates’ falsifying grassroots support. We need quicker and broader policies from these social media giants, or we could end up with a new kind of digital misinformation in our elections — paid, domestic and punny.

Serena Saunders is a senior public policy major and a graduate student in public policy. She can be reached at serena@sersaun.com.