By Angela Roberts and Luciana Perez-Uribe

Senior staff writers

A biting flash of air shot into the University of Maryland’s Memorial Chapel each time a bundled pair of guests cracked its doors Friday evening. The cold never lasted for long, though, the room’s reverberating warmth quickly enveloping it.

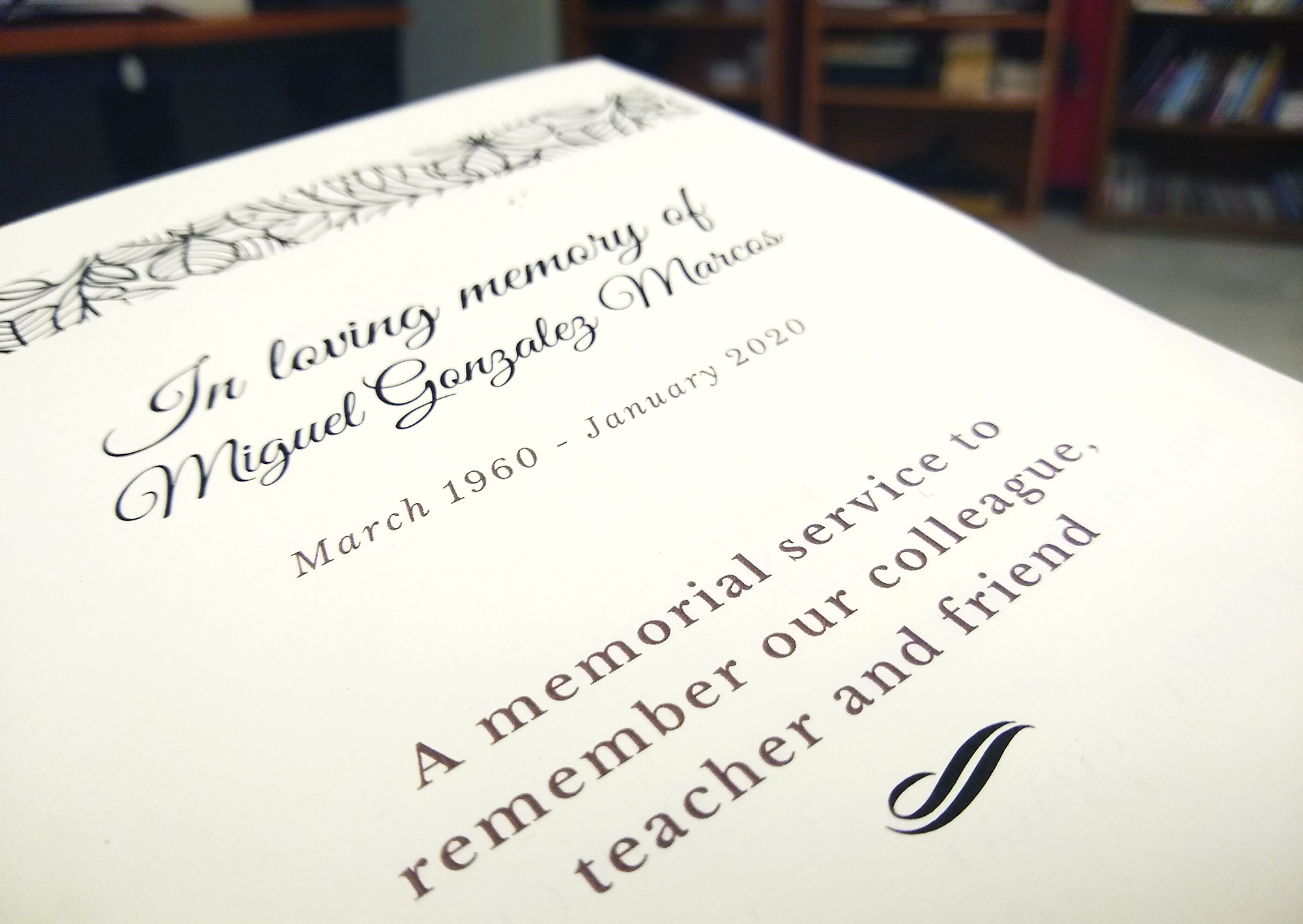

There were tears, off and on. Voices catching, thickening with grief. But as the sky outside faded from a gray-blue to an inky black, a resounding strain of gratitude moved through those who came to celebrate the life of Miguel González-Marcos: They all felt they had been so lucky to have called him teacher, colleague or friend.

González-Marcos, a public policy professor at this university, died near the end of January after unexpectedly falling ill while visiting family in Panama. He was 59.

Those who knew González-Marcos praise his luminous intellect, heroic character and magnetic personality. They describe him as an impassioned international attorney, an incessant activist for citizens of his beloved Panama, a man whose moral compass never wavered.

But mainly, they remember the beaming love and devotion he had for his students — his belief in their potential, his wonder at their intelligence. As public policy school dean Robert Orr opened the memorial service, he announced he did not only want to celebrate González-Marcos as a friend and colleague, but also as “the epitome of a brilliant and lovely teacher.”

“It always came back to his students — what he wanted to teach his students, what he wanted to learn from his students,” he said.

Throughout the service, many of the professor’s former students shared memories from their time with him. They recalled their fluid and never-ending debates, and the moments when González-Marcos offered them support when they needed it the very most.

Laura Spector, a senior and first-year public policy master’s student, remembered how interested González-Marcos had been in an internship she’d held while in his class. He’d always ask her about it, and tried to relate her duties to subjects discussed in class.

And after students finished his course, Spector said González-Marcos had a request for them.

“‘In the classroom, I am Professor González-Marcos, but the second you turn in your final paper, call me Miguel,’” she recalled him saying.

González-Marcos mainly taught graduate-level courses, such as Ethics and Leadership and the Moral Dimensions of Public Policy. Ana Khundzak, a former public policy master’s student who was first taught by González-Marcos in 2017, said the professor would sometimes bring food for the whole class.

Khundzak took more classes with González-Marcos through the 2018 academic year, then later asked him to mentor her as she wrote her final project paper. She remembered the attention he showed to each of his students.

“He knew everybody’s names, first of all, which professors don’t really do that much,” she said. “He would talk to everyone in person, he would make jokes in the class but always … made sure that we knew what he was teaching.”

Adnan Younis Lodhi, who attended the public policy school in 2014 while on a Fulbright scholarship, also recalled his former professor’s kindness and compassion. He’ll remember González-Marcos’ sense of humor, he said, which sprang with lightness and was never demeaning.

“I found him free of major biases and prejudices, which is a hallmark for a true scholar and a great human being,” he said.

Before becoming a professor at this university, González-Marcos worked as a legal and policy adviser for the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization. He also practiced law with a variety of firms, eventually establishing his own in 2008.

González-Marcos connected with students at the University of Panama’s law school, teaching courses and seminars on subjects such as constitutional law, human rights and administrative law.

Back at this university, though, public policy school associate director Michael Goodhart said he already misses his colleague’s deep, booming laugh. González-Marcos was always thinking of other people, Goodhart said. He described emails González-Marcos would send him when he saw something that reminded the former professor of his colleague.

Thomas Hilde, another public policy professor, remembered the time he spent with his colleague when they were both fellows at Harvard University, researching tax havens. González-Marcos had a moral concern with the subject, Hilde said, as it highlighted how the law’s structure allows for financial misbehavior.

Hilde also fondly recalled memories he built with González-Marcos outside of work. They met for the first time back in 2008, when they both lived in the same Washington, D.C., neighborhood. They’d go on long walks together, Hilde said, talking about philosophy and law and making fun of themselves. It became time they both treasured.

His colleague and friend was special, he said — selfless and devoted to his fellow human beings.

“There were ways in which he would sacrifice his own well being, whatever that might be, to make sure someone else was better off,” Hilde said. “His own personal struggles, when he had them, were never part of that interaction. That, to me, speaks of the sort of generosity of spirit and decency that really made him unique.”