The weekend of May 20, 2017 started like most other weekends for Eartha Govan, an Army lieutenant colonel who once led Bowie State University’s ROTC program.

It was her birthday, but she woke up early anyway for her Saturday morning fitness training, a vestige of her earlier days in the military.

At about 7:30 a.m., she got a phone call. The news on the other line — from the father of her ROTC student, Richard Collins, whom she’d recruited into the program about four years before — shattered what would otherwise be a joyful day.

While visiting the University of Maryland the night before, Collins had been killed, his father said. He’d been stabbed to death standing near a campus bus stop, waiting for an Uber with his friends. Another student was arrested shortly thereafter.

“I kept asking him: ‘What did you say?’, ‘I can’t hear you,’” Govan said when she heard about Collins’ death. “I said, ‘That can’t be possible.’”

Collins was a newly minted second lieutenant, a few days from graduation.

“My heart was broken. It still is,” said Govan, whom Collins’ parents call his “military mom.” “We still can’t believe that he’s not here.”

For Govan, two years and two bittersweet birthdays have passed since then. And though they’ve been fraught with the pain of justice deferred, they’re brimming with the power of cementing the legacy of a fallen soldier.

On Monday, the former Maryland student charged with a hate crime in Collins’ killing is set to stand trial, after four different delays pushed it back about two years. But amid the painful setbacks, Collins’ family established a foundation in his honor. They’re pushing for full military honors for ROTC graduates who die before they begin serving, for hate to be better addressed on college campuses and across the country — and, most importantly, for remembrance.

Last week, more than two dozen cadets in Bowie State University’s ROTC program filled a ballroom at their university, where they were honored as the first recipients of the 2nd Lt. Richard W. Collins III Leadership with Honor Scholarship, supported by an annual $1 million fund from the state.

The cadets will receive several thousands of dollars spread out over two semesters, said Montrose Robinson, ROTC recruiting operations officer at Bowie State. At Thursday’s ceremony, they watched as Collins appeared on the screen before them in Bowie State’s Student Center.

It showed Richard at his happiest — at his commissioning ceremony, just a few days before his death. He stood at the lectern, leaning carefully into the microphone, and described the day he decided to attend Bowie State.

“No other day besides this one has brought me such joy or happiness,” he said, smiling broadly.

Dec. 12 should have been Richard’s 26th birthday. Instead, it will mark the first anniversary of the 2nd Lt. Richard W. Collins III Foundation, which is spearheading efforts like the scholarship.

In the first year it’s existed, members of the foundation have made meaningful strides promoting legislation, and connected with other foundations along the way, including the one established in honor of Heather Heyer, the woman killed protesting white nationalism in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017.

And Dawn Collins, Richard’s mother, said there’s more to come.

“This is only the beginning,” she said.

“Who He Was”

With the trial finally beginning, Collins, whom friends and family knew as a vivacious jokester and passionate leader, is on their hearts and minds anew.

Alfred Abramson, who was commissioned with Collins at Bowie State, looks at his friend’s name, etched into the metal of his military bracelet and the memories come flooding back.

The memorial bracelet is one of the few jewelry items permitted in the Army’s dress code. Abramson, a first lieutenant, wears it during training exercises at Fort Bragg in North Carolina, where he currently serves as a paratrooper — just as Richard would have.

“It’s sort of a reminder of who he was,” Abramson said. “In my lowest moments, thinking about him brings me back out of that. And I think it does that for a lot of people.”

Collins was the one Abramson and others went to for advice, and he was perhaps most well known for his leadership. Frequently, he’d give rides to cadets who couldn’t make it to early morning training, Govan said, to the point where he was almost late for training himself.

Hearing of his passing, just days after they’d prepared their speeches and uniforms for their commissioning ceremony together, was like a “shot to the chest,” Abramson said.

Driving home from a night out in Washington, D.C. ,when he heard the news, Abramson had to pull over. As the disbelief washed over him, he remembered his friend, who was always there for advice and encouragement — especially during his first day in ROTC.

“I was kind of having a rough time getting on with that sort of environment,” Abramson said. “I just remember Collins kind of coming in and pulling me to the side, and really helping me.”

Collins frequently took a leadership role, but he was quick to let other cadets do the same, said Lt. Col. Joel Thomas, who led the ROTC program during part of Collins’s time there.

“Not only was he a good leader, but when he was in a role that wasn’t in leadership he was a good follower,” Thomas said. “It’s easy for somebody to get sideways and forget that there’s times when we aren’t going to be in charge and we just need to be good teammates.”

In the movies, Thomas said, there’s this portrayal of military leaders — they need to be strict and unrelenting, they need to yell at the cadets. Collins wasn’t like that.

“I’ve been in the game a long time,” Thomas said. “But it was refreshing and also confirming to see that you can be who you are and still be successful.”

The scholarship established in Collins’s honor, which garnered over 50 applications, is meant to support cadets who share his leadership style. It’s also boosted interest in the program, said Lt. Col. Wesley Knight, professor of military science at Bowie State.

Over the past three years, between 10 and 15 students have graduated from the program each year, Knight wrote in an email. But this year’s freshman class was 26 students strong, he said.

The funds are designated for minority, in-state students. A quarter of the funds go to ROTC students at Bowie State, and the remainder is split between ROTC programs at other historically black colleges in Maryland.

Cameron Cuevas, a Bowie State ROTC sophomore who received the scholarship, said he’s planning for a future in the armed forces, following in the footsteps of his father. He’s learned a lot about 2nd Lt. Collins in ROTC, he said.

“I know he was an excellent cadet, that he was a scholar, and he was a mentor to other underclassmen,” he said. “So if I can be a mentor to underclassmen when I get ready to commission, I feel like I could have accomplished trying to continue his legacy.”

The Foundation

The Collins family’s efforts have quickly expanded into the legislative sphere.

In September, Maryland’s U.S. senators, alongside Reps. Steny Hoyer and Anthony Brown, proposed legislation that would grant military honors to ROTC graduates who die before receiving their first duty assignment.

That goal has been a cornerstone of Govan’s work for the foundation, and the bill is inching toward becoming law.

Provisions of the bill are included in both the Senate and House versions of the National Defense Authorization Act, the annual defense spending bill, which is under conference negotiations between the two chambers.

It would change the military’s death gratuity benefits to include ROTC graduates, provide for their life insurance and permit their families to have assistance from a military casualty assistance officer.

The bill would secure for other grieving families what the Collins family was denied, Govan said.

“We will always remember him as a selfless young man who put the needs of others before his own,” she said. “He loved the Army. He lived the Army values.”

Alongside the financial benefits they haven’t received, the family also missed the elements of a military funeral, like a military salute, a painfully conspicuous omission for a man who planned to give years of his life in service to the military, Govan said.

But in a ceremony last month, U.S. Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy presented the Collins family with a posthumous promotion for their son to first lieutenant — a meaningful gesture, Govan said.

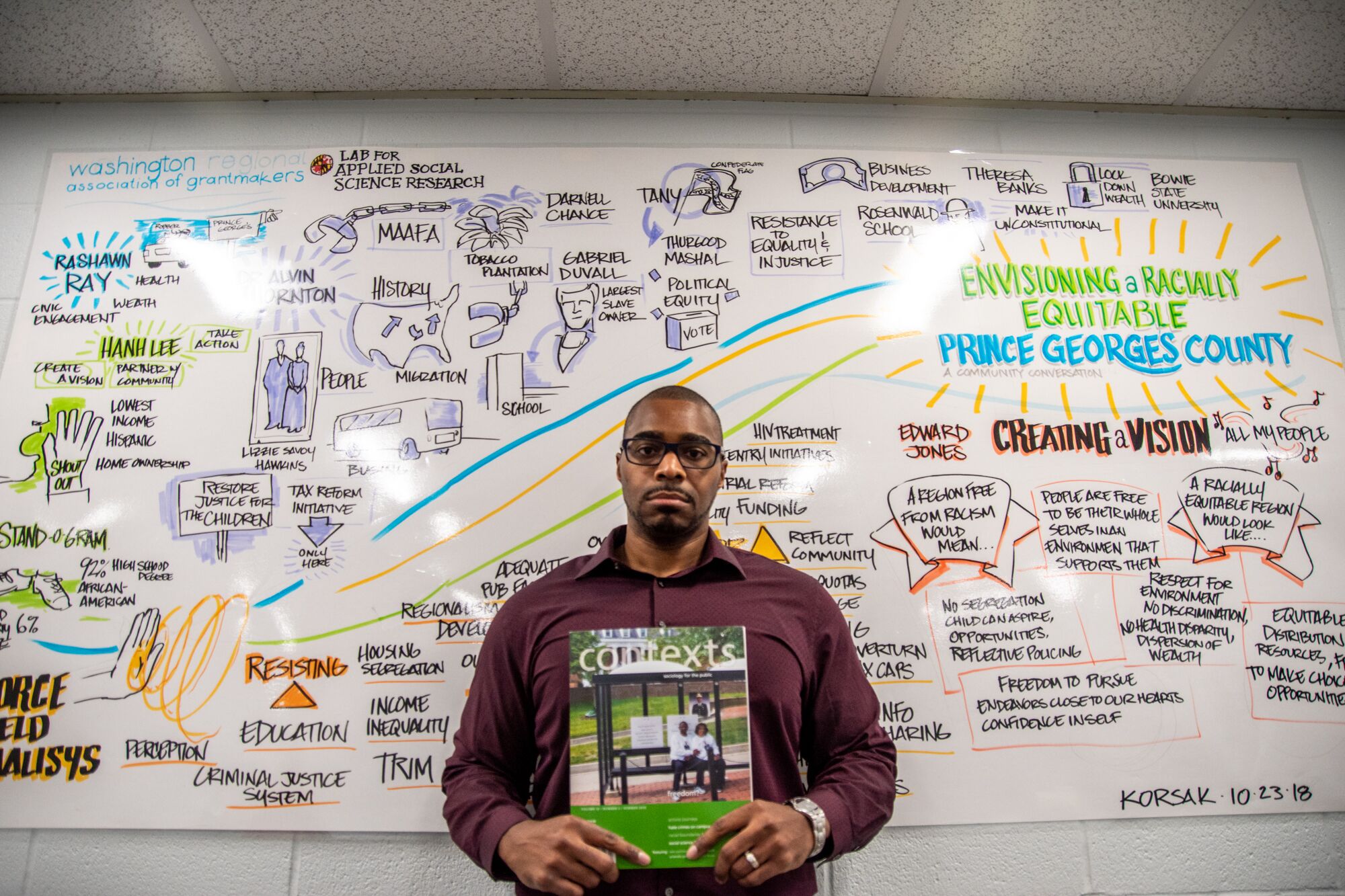

Meanwhile, Rashawn Ray, a sociology professor at this university and a board member of the foundation, has been pushing for more expansive hate bias legislation at the state and federal level in his capacity as a board member for the foundation.

Much of his work, he says, is raising awareness about domestic terrorism and hate.

“The bar for what we consider hate in the United States is extremely high,” said Ray, who is currently on sabbatical from his position at Maryland and working at the Brookings Institution in Washington, D.C. “[People] attribute things like hanging the noose or spray painting a slur to be free speech instead of a threat.”

Advocates for broader hate bias legislation notched a victory in Maryland during this year’s legislative session. In April, Gov. Larry Hogan signed legislation that would expand protections against hate crimes to include threats made against members of protected classes. As of Oct. 1, threatening a hate crime in Maryland is a misdemeanor punishable by up to three years in prison and a fine of up to $5,000.

“To minority groups, marginalized groups, these things actually are threats,” Ray said. “And people view what happened to Lieutenant Collins to be a direct result of people not paying attention to those threats, whether it be the administrators or police officers.”

Following the 2016 election, there were a spate of racist incidents on this university’s campus that drew concern from minority students.

On several occasions, students found posters dubbing America a “white nation” and decrying diversity hung in academic buildings, and in early May 2017, a noose was found hanging in a campus fraternity house.

But much of the administrative action addressing hate bias incidents came after Collins’ death, following university President Wallace Loh’s creation of a task force focused on diversity and inclusion, on which Ray served.

That group ultimately established a policy expressly prohibiting threatening conduct, and a university values statement.

The university has also introduced a log of hate bias incidents and brought on staffers to address them, but that log doesn’t include the punishments handed out after investigations, which is a cause of concern for some students.

“The bottom line is that efforts to hide behind free speech and protect people’s privacy clouds transparency,” Ray said.

“They have to battle perception”

The Collins family has also forged a bond with the family of Heather Heyer, the counter protester who was struck and killed by a car at a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017.

The two couples met for lunch in Alexandria, Virginia, over the summer, said Susan Bro, Heyer’s mother.

“We talked about our children. We talked about our heartbreak as mothers. We talked about our job, we talked about before all this happened,” Bro said.

To a certain extent, Bro feels linked to the Collins by the anguish of losing a child. But she said that her family’s experiences, and those of the Collins, have been different.

It was heart wrenching for her to realize, she said, that her daughter’s legacy felt easier to fight for, just because she was white.

“I can present Heather and … show her in a swimsuit sometimes, and they have to constantly keep him in uniform and refer to him as 2nd Lt. Richard Collins, and never let him be referred to any other way,” Bro said. “It was just a very sad contrast to me, how they have to battle perception.”

And, on top of that, the trial for her daughter’s killer has already come and gone, even though Heyer died months after Collins. James Fields Jr. was sentenced to life in prison for killing Heyer and wounding numerous others when he rammed his car into the crowd of counter-protesters at the rally. Fields pled guilty to 29 federal hate crime charges, a plea deal in exchange for prosecutors dropping a charge that could have led to the death penalty.

“I promised them that I would keep their son’s name floating to the surface,” Bro said. “So from time to time when I’m interviewed, I will note that he has not received justice and Heather did.”

The Collins family declined to be interviewed until the conclusion of the trial, which will start Monday and is set to extend through Dec. 19.

Fields’ trial was an emotional battle, Bro said, but she’s hopeful the legal process will bring peace to the Collins family.

“It took me about three weeks to get to a point where I could breathe again,” she said. “Sometimes just sitting and staring at the walls, because that’s about all you have emotional strength for at that point.”

At the University of Maryland

When student activists at the University of Maryland heard that Dawn Collins had been visiting the Montgomery Hall bus stop to keep it clean, they jumped into action.

“She shouldn’t have to return to the site of her son’s [killing] to make sure that it is kept in decent condition,” said Chandra Reyna, a doctoral student in the Critical Race Initiative, a program within this university’s sociology department focused on studying racial inequality.

Reyna, along with a handful of volunteers from the CRI and the university’s NAACP chapter, donned gloves and wiped the panes of glass on the bus shelter. They scrubbed the small metal seat and picked up litter on the ground alongside Ms. Collins.

Among them was Elonna Jones, this university’s NAACP president.

“It looked so much better after we were done. It was clean. It was neat,” Jones said. “And it wasn’t even something that I think most people realized — that it needed that little extra care.”

That bus stop has become something of a flashpoint for Maryland students in the years since then. For some, it’s a physical representation of a lagging administration out of touch with the needs of students of color.

After Collins’s death, the concern that he could have just as easily been any member of this university’s black community left students unsettled, Jones said.

“People come to not feel supported after that happened,” she said.

In the wake of Collins’s death on the campus, this university awarded him an honorary degree. The university has also held memorials for Collins, university spokespeople said, including shortly after his death and on the one-year anniversary of his killing.

“The university continues to think of the Collins family during this difficult time,” a spokesperson wrote in an email Friday.

But Ray said, at least to the Collins Foundation, memorializing Richard Collins is about far more than that one place. One idea that the foundation has considered, Ray said, has been to work toward establishing a center in Richard’s honor, perhaps tied to Bowie State, that would study hate and bias on campus and beyond.

To Ray, the center would be “a place for students to come together to actually do the work that is important to try to make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

Bringing together Bowie State, a historically black college, and Maryland, could strengthen the fight against hate, Ray said.

“That doesn’t mean just putting up a placard and saying, ‘Oh, we remember this space,’” he said. “It’s actually creating a space like a center or an institute where people can engage in innovative type of work that brings both campuses together.”