Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

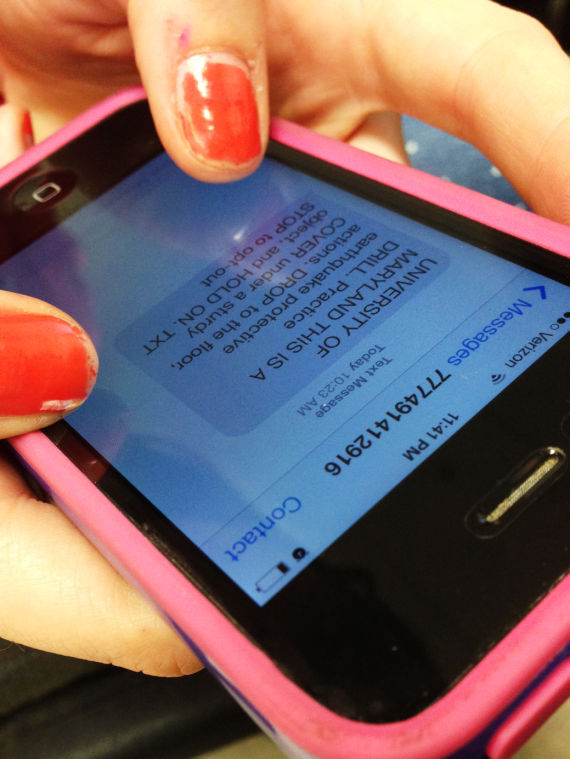

My email is clogged with alerts from the University of Maryland Police, and I know I’m not the only one. The messages range from notification of off-campus robberies to indecent exposures to “all clears.” While the high frequency of notices keeps students aware of their surroundings, the sheer amount of police alerts and their vague language have devalued the seriousness of crime in College Park.

Don’t get me wrong: Police transparency and crime awareness are crucial components for creating a well-informed and safe campus community. But the alerts have become excessive, with content that is a consistent script of vagueness — reporting an “all clear” because the subject has “left” or “fled” the scene of the crime — and has deviated from its mission to inform students, instead becoming fodder for countless jokes.

The driving force behind the constant police alerts is the Clery Act, a federal policy enacted in 1990. It requires colleges and universities to “issue a timely warning for any Clery Act crime that represents an ongoing threat to the safety of students or employees.” So when students get an alert about larceny-theft or an off-campus armed carjacking, it’s because the police are required to report them.

However, if a crime happens in Old Town, everyone gets the alert no matter if they’re a freshman living all the way on North Campus or a commuter student at home. One way the university could thin out the mass amount of notices is to only notify the area that’s impacted. I don’t really need to know if there was an armed off-campus carjacking at Adelphi Road, but the students in that area do.

According to the Department of Education, universities have the “flexibility to alert only the segment of the population that [the university] determines to be at risk.” So, if an event occurs at the Atlantic Building, University Police only have to notify students in and around that area. This selective notification might be a more efficient and effective way to gather information and create awareness around the area of the crime.

More importantly, it could decrease the campuswide reaction to area-specific crime. It’s the constant flow of alerts to all students that creates a culture of indifference about crime and police. People either don’t take them seriously, or they play up crime in College Park to be horrendous.

Other universities only send out crime alerts after the crime has happened and purposely don’t send out update alerts. At the University of Wisconsin, “Crime Warnings” only go out after a crime happens because the police “don’t want to send so many communications that people get annoyed and stop reading the emails.” This university could easily follow that method and only send crime alerts.

The police also need to strive for more clarity in their alerts. Is an area really “all clear” if a suspect has fled? The vague language in their notices is the stuff of memes. It’s important the details of the crime and suspect are released to the public. However, how beneficial are “all clear” alerts if the definition of an “all clear” scenario is murky at best? A simple fix lies in the intentionality of the language University Police use, as well as in using discretion in what updates are necessary.

Alerts from University Police are, obviously, important. But if the police really want students to change the near-comical reactions the alerts garner, they need to change the way they operate and notify students in a more specific manner.

Maya Rosenberg is a sophomore journalism and public policy major. She can be reached at maya.b.rosenberg@gmail.com.