Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

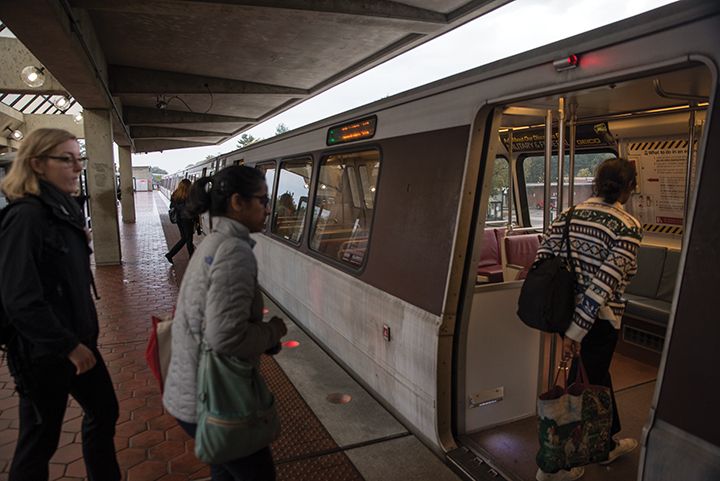

On Sept. 23, climate activists descended on Washington, D.C.’s main intersections as a part of Shut Down D.C., a movement to shut down the nation’s capital and demand that legislators take action on climate change. Dozens of protestors were arrested in the demonstration, drawing criticism from all sides, much of which showed concern for how low-wage workers would be disproportionately hurt over the protest’s intended targets, Washington elites. Amid the debate, D.C. Homeland Security was one of many organizations that took to social media to urge commuters to opt for public transportation to avoid the disturbance on the streets. This seems like a valid suggestion — until one factors in the disparities in Metro access for lower-income communities that have plagued D.C. for years.

I’m not here to bash the demonstration. I’m here to say that in addition to heating up the debate on climate justice, Shut Down D.C. also created an opportunity to discuss how Metro consistently fails the low-wage workers everyone seemed so concerned about when protestors blocked the streets. Regardless of your opinion on Shut Down D.C., if you really care about working class people, it’s imperative to acknowledge the constant struggles they face getting to and from work, rather than focusing on a single protest intended to cause disruption.

A lot has been written over the years about how Metro access disproportionately favors whiter, wealthier workers. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the number of African American workers in “rail-accessible” neighborhoods declined from around 33 percent to 24 percent from 2006 to 2008 and 2011 to 2013, while the percentage of white workers in neighborhoods such as these increased from around 50 percent to 56 percent. It also found that rail-accessible neighborhoods have a higher proportion of high-income workers.

This reveals a gap in Metro access that is harmful to lower-income communities because it’s harder for residents to get to work. Metro riders living in cities such as Gaithersburg and Reston who commute to the area around the White House can do so in less than an hour, whereas workers living just seven miles away in Anacostia or on the edges of Prince George’s County face commutes lasting well over an hour. For example, the southern tip of D.C., east of the Anacostia, not only holds a high concentration of commuters who take public transit, but it also is a predominantly black area where a large percentage of households earn less than $35,000 a year. Public transit remains far less accessible to lower-income people and people of color on a daily basis, hindering their daily commutes far more than one climate strike.

The long commutes low-income people face as a result of poor public transit access is just one consequence of this lack of services. Metro hours during the week, especially at night, also put low-wage workers at a disadvantage. In February, Metro scrapped a proposal to add late-night weekday hours. The trains currently stop running at 11:30. When paired with spotty transit access in low-income neighborhoods, these hours inconvenience night workers — who tend to earn less than their white-collar counterparts. As of March, Metro has pledged $1 million to subsidizing taxis and ride-sharing services for the workers that the service cuts affect. But, as many have pointed out, a $3 subsidy barely helps workers who commute between downtown D.C. and underserved suburban areas. Furthermore, this subsidy reveals an inherent lack of commitment to low-income communities and workers because it doesn’t include a real extension of services on Metro’s behalf, a point Metro’s union, ATU Local 689, made.

Clearly, both sides are right in pointing out how Shut Down D.C. disproportionately disrupted the commutes of low-income workers whose bosses may be less forgiving. Whether you believe the disruption was justified or not is up to you. However, the forces pushing workers from transit to cars originates from an institutional lack of concern that translates into fewer services for low-income communities — and that can’t go ignored. Until this disparity is addressed, anyone claiming to show concern for these workers’ commutes for one day out of the year should challenge themselves to examine the deeper daily disruptions at play.

Caterina Ieronimo is a sophomore government and politics major. She can be reached at ieronimocaterina@gmail.com.