Orlando von Einsiedel has long felt comfortable in risky situations. He’s spent his adult life in combat zones and man-made disasters filming documentaries about what people persist through.

So, when it comes time to talk about his baby brother, whose name he’s hardly mentioned in over a decade, it makes sense that he would want to do so out-of-view. He would do it with a camera turned on those who loved Evelyn and understood his pain.

Evelyn, a documentary released on Netflix this week, captures three siblings’ five-week journey across Great Britain – walking the places they spent their childhood with their nature-loving brother.

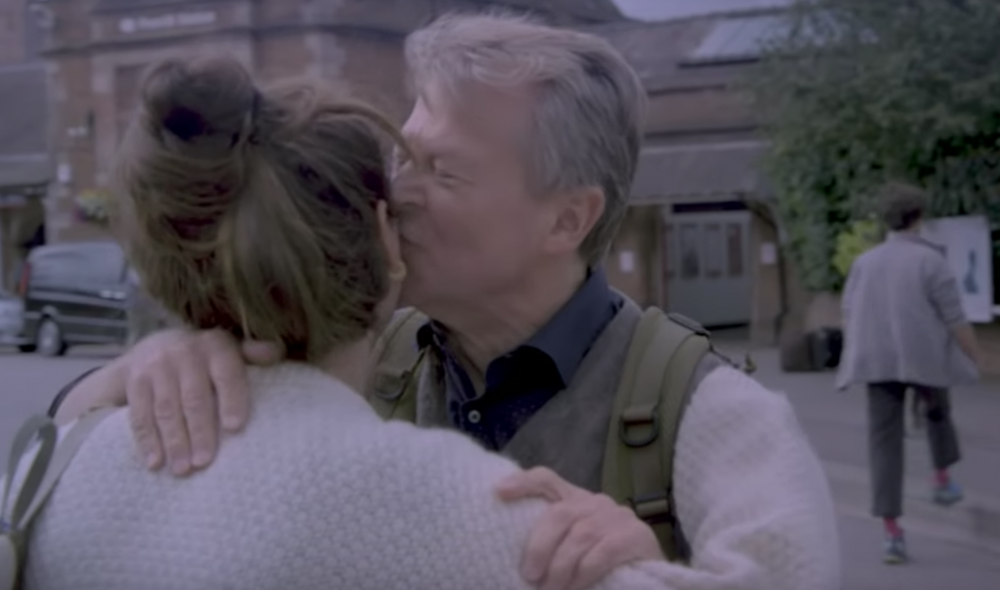

Along the way, Orlando, Gwendolen and Robin are joined by family and friends who attempt to remember Evelyn together for the first time in the thirteen years since Evelyn died by suicide in the family’s backyard.

[Read more: Review: Country music supergroup The Highwomen delight on their epic debut album]

It’s difficult to write a review on Evelyn’s qualities as a film, as a 100-minute feature on grief. Instead, there is simply a genuine experience of being on a walk, with a family that has no idea how to face their pain.

The tension of the siblings becomes our own. With occasional cuts to videos and photos of a young, care-free Evelyn among his family, the stark absence of a fourth sibling among them is impossible to ignore. The memory of Evelyn is constantly with them, and we watch as they try to transform this energy from a burden to a memory.

Evelyn is an honest film. After more than a decade of grief, the family can hardly stand to speak about their brother, and the fact that he ever even existed. It’s still too painful. There’s a desperation for their burden to lighten and the uncertainty of whether or not they’ve achieved healing.

If you’ve dealt with family trauma, you know the difficulty with not knowing how to heal when it’s not just up to you. No one knows how to pick up the pieces.

[Read more: Why we shouldn’t mourn Scarlett Johansson’s career]

Evelyn acknowledges this struggle. Evelyn’s best friend Leon, who joins the siblings for a while, points out how Orlando feels the right to delve into others’ pain while refusing to confront pain himself. Each has a role to play in this journey, and Leon is the catalyst.

Their mother tries to keep her son’s memory alive. Their father wrestles with guilt and takes it out on others. Gwendolen and Robin need to feel like they still have a family. And Orlando, the reason for this journey and this documentary, has to pause and make himself the subject as well as the filmmaker.

The tension is sometimes so high that Robin throwing a pillow at Gwendolen is enough to bring her to tears. Like many adult siblings, they revert to childish attitudes when they’re with each other — something I catch myself doing around my own siblings, although we’re all in our 20s and 30s.

“Just because we’re talking,” Gwendolen says through tears. “It’s not getting less painful or less traumatic.”

But along the way, there is genuine surprise from the family and the audience as they run into passersby who ask about the film, and reveal their own histories in the process. An ice cream salesman who lost his mother to suicide four years ago. A pair of sisters whose father died that day. A veteran who has lost three friends to suicide since returning from combat, who cries with them.

It is clear you can’t heal anything that you can’t confront. Evelyn’s ability to capture the never-ending struggle of grief is heart-piercing. There is no solution to the problem, but after five weeks of backpacking through their brother’s favorite childhood places, the family goes from being unable to say his name to actively asking each other about him.

Was he taller than you? What did Mom say when she told you? Do you remember how obsessed he was with skateboarding? Do you remember when he tried the first time? Did you know it was going to happen again? What are the ten things you would use to describe him?

When their mother unabashedly mentions that one of the first things she thinks about are his loud farts, they all break down in laughter, admitting that was on their own lists as well.

There’s no solution, but there is the relief of finally, after years and years and years, admitting what’s there and what isn’t.