Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

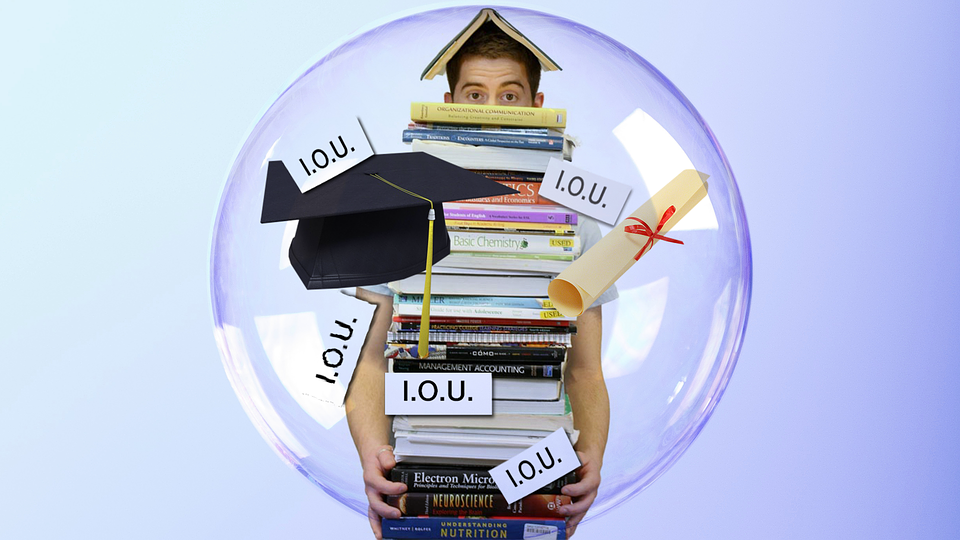

Student debt today is a bit like Simon and Garfunkel albums in the ‘70s: If you went to college, you probably have some, or did at one point. They might as well give it to you at orientation along with those free condoms resident assistants are always trying to give you.

Democratic presidential candidate and amateur racial identity theorist Sen. Elizabeth Warren has had enough. On Monday — Vladimir Lenin’s 149th birthday — she revealed her vision of what is to be done about America’s $1.5 trillion of student debt.

Warren’s plan is a start, but it doesn’t go far enough. Tuition-free college was bold when Bernie Sanders borrowed it from Ralph Nader in 2016, and Hillary Clinton adapted it from Sanders (making it a good, but boring, idea). But Warren doesn’t just want free college. Her plan would also cancel up to $50,000 of existing student debt for those with a household income under $100,000 and “substantial” amounts of debt for those with household incomes in the $100,000 to $250,000 range.

This is all great. However, the trouble is that wealth — and debt — accumulate. Anyone who has paid back a student loan is still poorer than they should be by precisely the amount they repaid. A new graduate who owes $40,000 in debt payments is $40,000 poorer than they should be, but so is someone who graduated 20 years ago and fully paid off $40,000 of loans. In the latter case, the $40,000 decrease in net wealth is the absence of $40,000 that someone earned but didn’t retain. But the effect in both cases is a $40,000 reduction in net wealth due to student loan payments.

Yet Warren’s plan treats the two cases differently. The new graduate gets their $40,000 debt erased like it’s a Midwestern state on Robby Mook’s checklist, while the person who graduated 20 years ago paid their debt gets no compensation at all.

There is no principled justification for this difference. There may be political reasons, of course. Canceling all student debt and paying back past debt will be more expensive — in terms of governmental expenditure, at least — than only canceling outstanding debt. But there’s no point in pre-emptive compromise. As a country, we need nothing less than full loan reversal: cancellation of outstanding debt and repayment of debt payments that have already been made.

How did we get here? College was once basically finishing school for snobs — a special place for wealthy men whose idea of a good time was getting stupidly drunk and pretending to be a philosopher. Since the GI Bill, this idea has changed in America. As college transformed from liberal education to advanced job training, prices soared and loans necessarily increased. Boomers built a wall around employment and made their kids pay for it.

This transformation is bad. Colleges advertise job placement rates even as administrators wax poetic about the “transformative power of education” and other liberal arts-esque phrases that don’t mean anything now, if they ever did. The American university system is half-career program and half-aspirational liberal arts program, so it’s expensive — yet intended for the many. Even at the University of Maryland, general education requirements retain the breadth of the liberal arts era but throw in mind-numbing career advancement classes like “Professional Writing” and “Oral Communication.”

It’s not exactly a dumpster fire. The American university system is more like a Snapchat redesign: The pieces don’t go together, nothing’s where you expect, but we keep using it because quitting would just mean being left out. Financing higher education is the most pressing problem, but in a sense, it’s the easiest to solve: Tax the rich, reverse the debt and pay for tuition going forward. Peeling apart career building from self-improvement is a harder task.

John-Paul Teti is a senior computer science major. He can be reached at jp@jpteti.com.