College Park is considering transitioning to a voucher program for its 108 public housing units, the city’s housing authority told the city council Tuesday.

Under the city’s current system, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development subsidizes low-income housing and funds operating and maintenance costs.

With a voucher program, landlords would lease directly to residents. While the voucher program offers the city’s housing authority a higher income, city officials fear it’s a move toward privatization.

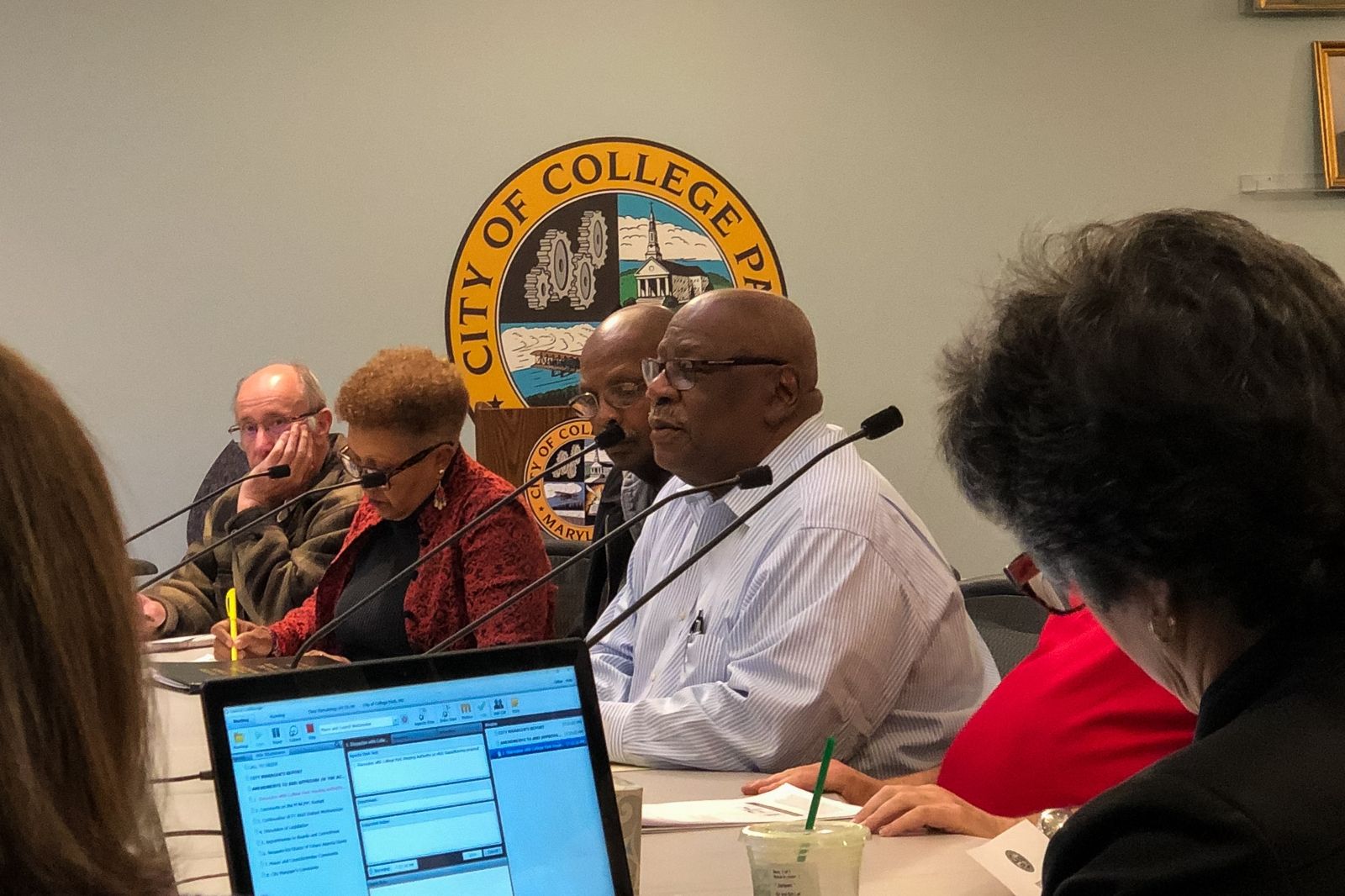

“This would be a big change for our city,” Mayor Patrick Wojahn said.

[Read more: Alloy by Alta brings more housing to College Park — but UMD students worry it’s too pricey]

The proposed changes are a result of a more than $26 billion backlog HUD is facing in operating costs. HUD has set a goal to reposition 105,000 public housing units nationwide to “a more sustainable platform” by Sept. 30.

Despite HUD’s frequent phone calls and efforts to persuade them, the College Park Housing Authority told council members at Tuesday’s work session that they’re wary.

“HUD told us it had to happen immediately, and it turns out that’s not quite the case,” said James Simpson, the housing authority’s executive director. “We’re still going to take our time.”

Under the current system, HUD funds operating and capital cost and pays the difference between actual market rent value and what the low-income resident can pay — which can’t be more than 30 percent of their income.

For the mostly elderly and disabled residents of College Park’s public housing, that’s about $300 a month, Simpson said.

[Read more: New UMD graduate housing could be coming to College Park]

Under a voucher program, landlords would lease directly to low-income residents who receive them and the federal government would similarly pay the difference in rent. The distinction is that residents could seek housing elsewhere.

HUD says transitioning to a voucher program could increase the city’s public housing authority’s income by 75 to 80 percent, which has led other local authorities to jump on the offer, Simpson said. However, the new program has more unknowns than certainties, he said.

One of the biggest unknowns is whether the College Park Housing Authority would continue to be a public entity, or instead become a private or nonprofit organization.

“It’s a different kind of animal completely,” Simpson said, adding that they do not know what impact privatization could have on the housing authority.

Additionally, if the housing authority decides to go with vouchers, it can no longer rely on funding from HUD. Funds would come from nonprofits or the housing authority would need to apply for state grants, Simpson said.

“If HUD pulls out, that’s it. We’re on our own,” he said. “We may be able to keep it up, or we may not. I don’t know if we want to take that chance, but I do know we want to proceed slowly.”

But it’s similarly clear that the current system might not be sustainable.

“If we stayed the way we are, we would continue to receive funds to do repairs,” Simpson said. “How far out that would take us, it’s hard to say.”

In November, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development sent out a letter to public housing authority executive directors outlining the agency’s proposal and reasoning.

“The capital needs of our nation’s public housing inventory has outpaced Federal funding for much of the past decade,” Dominique Blom, the general deputy assistant secretary for the Public and Indian Housing office, wrote in the Nov. 13 statement. “The [PIH] is focusing on repositioning public housing by providing [public housing authorities] with additional flexibilities, allowing communities to develop locally appropriate strategies to preserve affordable housing.”

Many officials, like District 3 Councilman John Rigg, expressed concerns about potential privatization of low-income housing, worrying that it could eventually take the housing program out of the hands of a public entity.

“This is fraught with hazard,” Rigg said. “We have a real asset in our city, and this is an asset that allows us to provide affordable housing for people who are economically vulnerable but are assets to our communities in many, many ways. And to the extent that the voucher program undermines that or privatizes is, that strikes me as very troublesome.”

While the decision is up to the housing authority, council members empathized and offered to write letters, apply for grants and help in any way they could.

“If we can throw our weight behind you, we’re here to do that,” District 2 Councilman P.J. Brennan said.