Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Last week, I discussed the issues presented by problematic media and the circumstances under which its consumption is morally acceptable. I used what I called the “private consumption principle.” It’s fine to read a morally dubious book or watch a morally dubious movie as long as you: obtain it in a way that doesn’t benefit anyone awful, consume it in private so as not to broadcast immoral messages to receptive audiences, and regard it with enough skepticism that you aren’t persuaded by the problematic components.

But, of course, we don’t always consume media in this way, nor should we. This week I’ll more closely examine cases not covered by the private consumption principle, starting with cases of media created by problematic people.

It should come as no surprise that it is morally wrong to obtain media from problematic creators in a way that benefits them. To illustrate: Many women have accused R. Kelly of abusing them. If you buy an R. Kelly album, you’ll give him more money, which he very well might spend abusing women. Ergo, don’t buy R. Kelly albums.

There are, however, plenty of ways to obtain media that don’t benefit the creator. Books can be checked out from the library, not all movies/TV shows pay their actors royalties, and Spotify’s payouts are so small as to be morally negligible. (Of course, one can always steal/pirate such things, but the moral implications of stealing from bad people is a question for another column.) So suppose one obtains media from a problematic creator without directly benefiting them. Can one do with said media what one likes?

Not necessarily. Consumption of media can benefit the creator even if obtaining the media did not. After all, when you broadcast an artist’s work, you increase their cultural capital, notoriety and relevance — their “clout,” so to speak. In the wrong hands, this kind of power is much more dangerous than money, so it’s wrong to lend it to those who would abuse it. For this reason, broadcasting media from a problematic creator in a way that extends their cultural capital is also morally wrong.

But what about creators who can no longer leverage their notoriety for evil, such as those who are deceased? As they say — or, at any rate, should say — dead men have no clout. These cases require further examination. I submit the relevant criterion is whether the artwork transcends the creator: if the most salient, interesting or notable characteristics of the artwork have to do with the work itself rather than its creator. If it does, then broadcasting the work without caveat is morally acceptable. If not, doing so might be taken as endorsement or normalization of the creator’s behavior. I’ll illustrate with two examples.

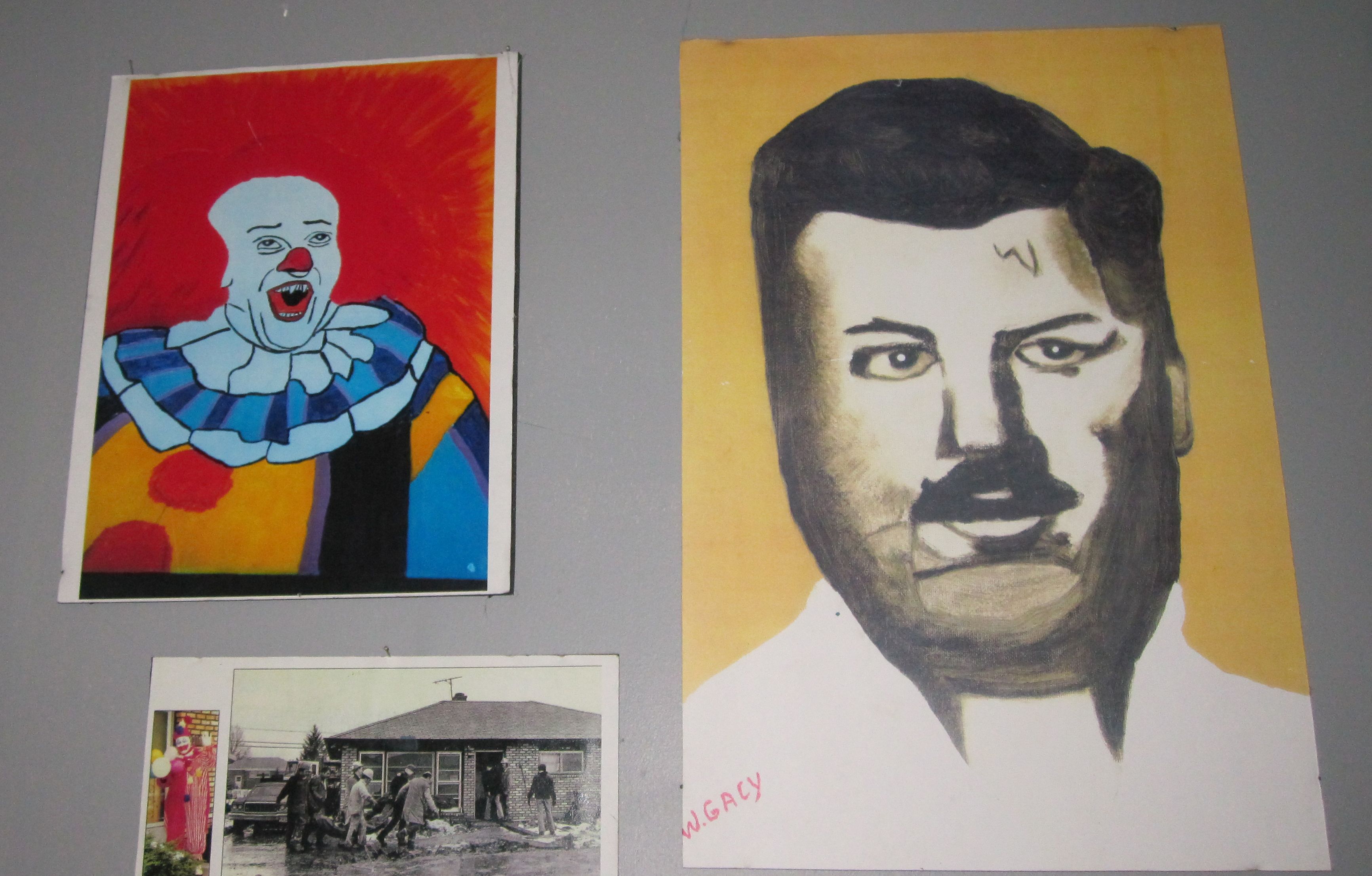

On one extreme, consider the series of stunningly mediocre artworks created by serial killer John Wayne Gacy. As artworks, they’re totally unremarkable, except for the fact that they were created by a serial killer. The artworks totally fail to transcend their creator, so exhibiting the work of John Wayne Gacy without extensive discussion of his horribly immoral actions is morally wrong.

On the other extreme, consider the works of Ludwig van Beethoven. To my knowledge, he did nothing particularly heinous by the norms of his day, but by the 21st-century standards, he was almost surely a virulent sexist and racist. Still, the most salient thing about Beethoven’s works isn’t that they were composed by a (probably) bigoted 18th-century German man, it’s that they are astoundingly beautiful pieces of music. They transcend their creator, so performances of Beethoven’s music don’t require footnotes about his bigotry.

Between these extremes is the enormous gray area of works by mildly problematic people who’ve created pretty good art. Such cases are often quite complex but can be addressed through the same line of reasoning. That said, one can always play it safe by including caveats about the problematic actions of a creator when broadcasting their work even if it might not be strictly morally necessary.

There are two caveats. First, the issue of problematic creators applies only to art. The moral value of claims about the world, like scientific theories or philosophical frameworks, lies entirely in their truth or falsity and has nothing whatsoever to do with their creators. Evolution is no less true because Darwin might have beeb racist.

Second, none of the arguments I’ve made so far have invoked the utilitarian position: That the aesthetic value of an artwork might outweigh the harm done by its creator. I happen to think this is very often true, but my arguments hold even if you don’t think the ends ever justify the means when it comes to problematic creators.

Joey Marcellino is a junior jazz saxophone, physics and philosophy major. He can be reached at fmarcel1@terpmail.umd.edu.