Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

The idea of a Green New Deal has spread with astounding strength recently, given that the policy platform looks dramatically different depending on whom you ask. Drawing inspiration from former President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal — which addressed poverty and poor infrastructure in the wake of the Great Depression — a Green New Deal aims to address the intergenerational challenge of climate change and the enormous growth of wealth inequality.

While Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass.) have introduced a Green New Deal resolution in the House and the Senate, respectively, the documents essentially declare their intentions instead of moving to achieve anything. It’s a start and better than nothing, but it only lays out broad policy goals; more specific details are necessary. To start, in order to facilitate a transition away from fossil fuels, the Green New Deal must include a provision moving toward fare-free public transit.

While it sounds radical and downright unaffordable, it’s been done in several cities around the world with success. Estonia’s capital, Tallinn, is a city of well over 400,000 inhabitants and has had free public transit for locals since 2013. Chapel Hill, North Carolina has had free bus transportation since 2002 and in doing so, has increased their annual ridership from 3 million to nearly 7 million. Many smaller jurisdictions, including 56 small cities across Europe have implemented fare-free public transportation programs.

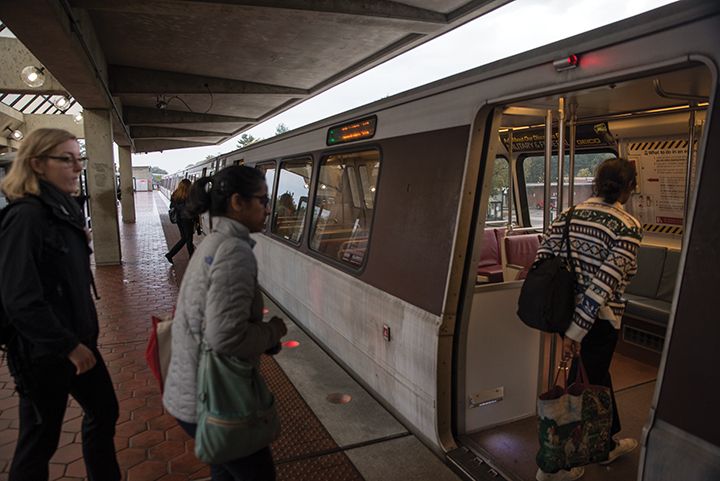

Anyone who has ridden the Metro knows that fares can be exorbitant, and the infrastructure hasn’t been well cared for. Ridership has been declining, track work seems to be never-ending and late-night service was cut a few years ago — with little chance of restoration, given the Federal Transit administration’s warning that it would cause WMATA financial hardship. Some might say that going fare-free would be the straw that broke the Metro’s back.

But cities that have experimented with going fare-free have found that many operational costs, such as fare vending machines, are associated with fare collection and preventing fare evasion. Without fares, these costs go away. In Tallinn, policymakers found that revenue from fare collection represented only a third of the transportation operational budget to begin with.

However, it’s not enough just to heavily incentivize the use of public transit. In order to pay for accessible public transport, policymakers need to actively disincentivize the use of cars with expanded gas taxes and tolls, as they disproportionately harm our environment and effectively threaten the future of our existence.

Furthermore, fare enforcement has proven to be a problematic process that disproportionately targets people of color. In Washington, D.C., 91 percent of summons for Metro fare evasion were issued to black residents between January 2016 and February 2018, and violations can be punishable by a fine of $300 and/or 10 days in jail. A recent push to decriminalize fare evasion in the District was vetoed by Mayor Bowser and derided by WMATA but passed nonetheless due to the Council’s override of the mayor’s veto. Without fares, there’s no need to punish those who can’t afford public transit.

Fare-free public transit is the kind of public investment that would radically shift our nation toward carbon neutrality, making it a perfect addition to the Green New Deal. An article arguing for free public transportation in Jacobin astutely observed that “we don’t put coins in street lamps or pay by the minute in public parks.” Why shouldn’t public transit be a part of that same package of public goods?

Emily Maurer is a junior environmental policy major. She can be reached at emrosma@gmail.com.