Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

It seems that in 2018 the news is uniformly depressing, horrifying and above all exhausting, with this week being no exception. While there’s too much at stake to tune all the way out, or for too long, for the sake of one’s sanity it’s important to occasionally focus on some of the good in life.

In that spirit I’d like to use my column this week to reflect on and to some extent defend a genre of music that has recently brought me a lot of happiness, and is a source of calm in an otherwise frantic, crazy world. I speak of none other than lo-fi hip hop.

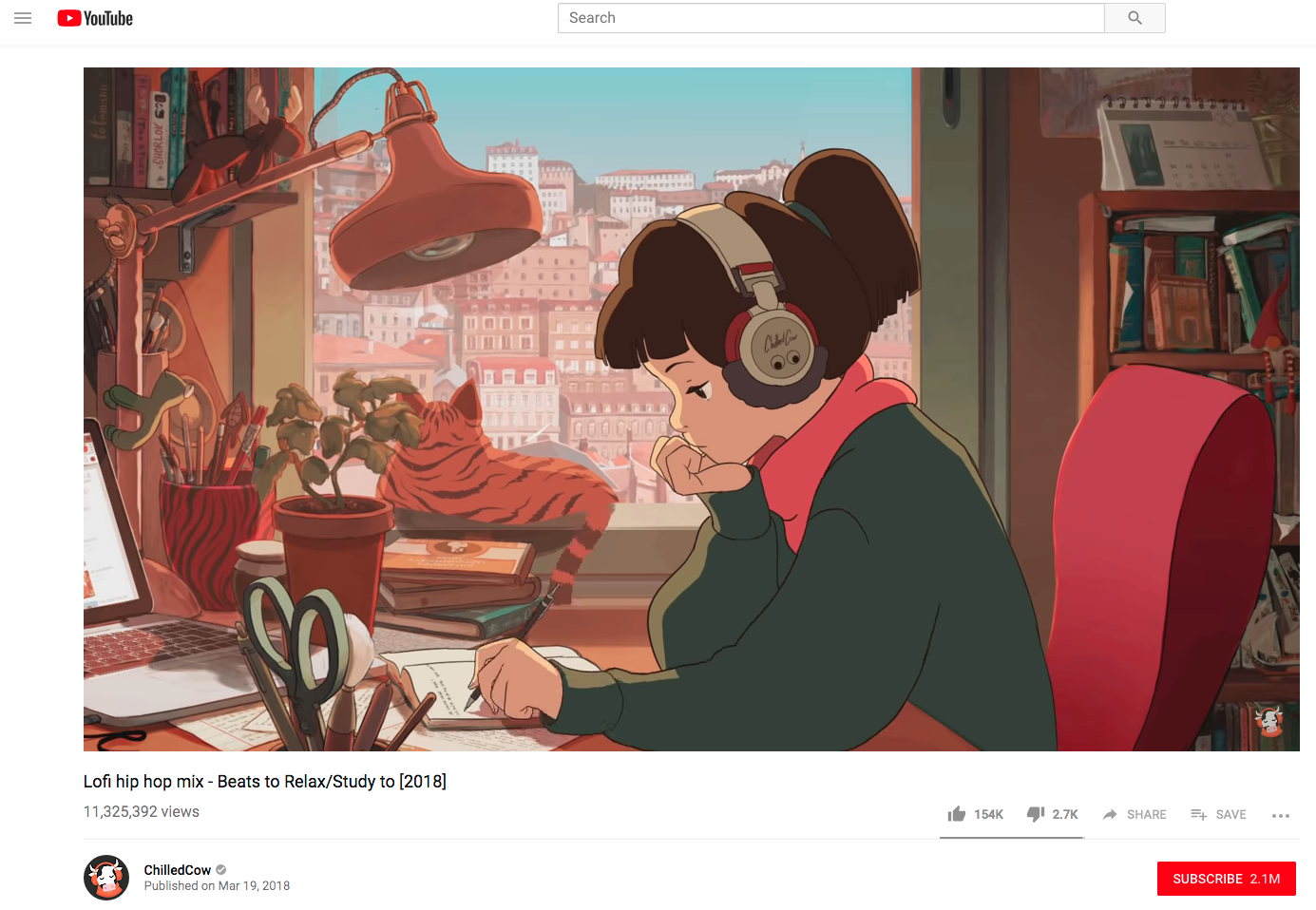

If you spend much time on YouTube, you’ve probably come across one of the numerous 24/7 streams or hours-long compilations that surged in popularity beginning in early 2017. Bearing titles like “Lo-fi hip hop radio 24/7 – chill study/relax/gaming beats,” the videos invariably feature a gif of an anime girl studying, playing video games or the like; they’ve slowly become a meme in their own right [2].

Both the glut of such videos and their meme-ability are functions of the ease with which lo-fi can be produced. For those unfamiliar with the genre, the typical lo-fi tune consists of a loop from a jazz recording — usually piano or guitar — with an added bassline and sampled drum beat. The loop is stripped of low and high frequencies and layered with a sample of vinyl record static, simulating the low-fidelity recordings of the early 20th century (thus, “lo-fi”). This affair is stretched out to two or three minutes, and boom, you have a lo-fi hit.

Given this apparent simplicity, it might come as a surprise how musically effective lo-fi can be. Sure, it isn’t music that anyone will be heading to the club for, but that isn’t what it purports to be — it’s music to study/relax/chill/game to. So what is it about the musical equivalent of a screensaver that’s so compelling?

For one, lo-fi producers have a habit of sampling really good jazz. I listen to a fair amount of classic jazz albums, both for my edification as a jazz major and for pure enjoyment. It’s amusing how often I’ll recognize a melody or fragment of a chorus, not from my classes or time playing, but from a lo-fi tune. Bill Evans, Wes Montgomery, Joe Pass, Stan Getz and Chet Baker are some of the most influential names in jazz, and also probably the biggest contributors to the lo-fi canon.

Because of this association, lo-fi listeners get the harmonically rich, intricate and often quite beautiful melodies, voicings and phrases that jazz has to offer without the engaging element of constant improvisation that makes it difficult for me to listen to jazz while studying or doing something else requiring focus. This backdrop plus hip-hop beats makes for a combination that’s musically enjoyable in its own right.

That said, what makes lo-fi “lo-fi” isn’t the jazz or the hip hop, it’s the facsimile of recording technology from an earlier age, when jazz was the hip hop of the day. And I think it’s that aesthetic that makes lo-fi as compelling as it is. Lo-fi has the peculiar ability to induce a sort of nostalgia for an unspecific earlier time; paradoxically, one that most of its listeners have surely never experienced and to which certain elements of the music are totally alien.

There’s a name for this strange sort of feeling: “anemoia,” defined as “nostalgia for a time you’ve never known.” At the risk of reading into things a bit too profoundly, I suggest perhaps the emergence of lo-fi as a genre is related to the growing anemoia of our cultural consciousness.

From the directionless desire to “Make America Great Again,” to the progressive callbacks to the days of the New Deal or the civil rights movement, to the “moderate” yearning for a time when “politics was civilized,” I think lo-fi taps into the pervasive feeling that any time must have been better than now. Regardless of whether that sentiment is true, lo-fi functions as a valuable sort of musical escapism that the unending stream of horrors that is 2018 necessitates.

Joey Marcellino is a senior jazz saxophone, physics and philosophy major. He can be reached at fmarcel1@terpmail.umd.edu.