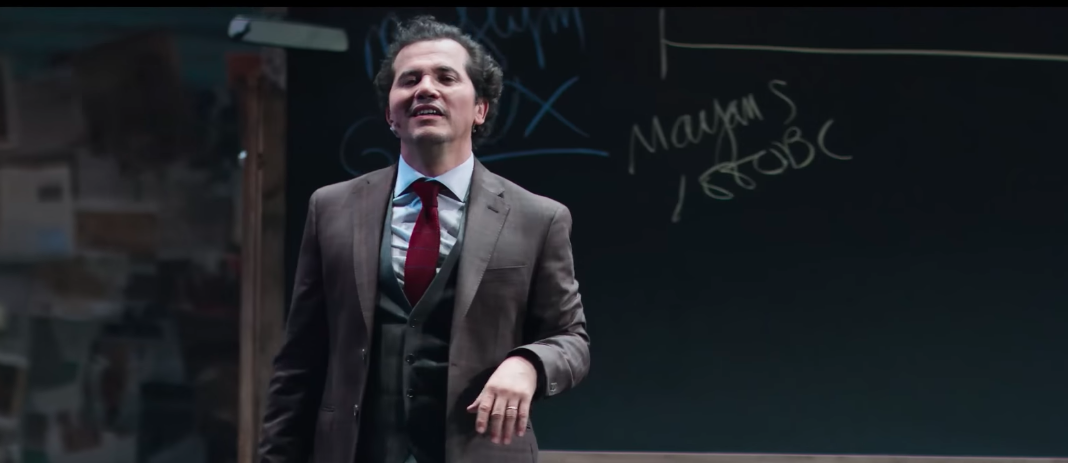

John Leguizamo’s Latin History for Morons is, in every sense of the word, a triumph. The one-man Broadway show presents Leguizamo’s desperate attempt to learn 3,000 years of Latin history and find role models to instill confidence in his bullied son.

Leguizamo’s frustration is visceral, because no matter how successful he is in telling the story of Latin history to the audience, he falters every time he describes being confronted by a white person who wants him to prove his worth. The significance of what he’s saying to us is so clear, yet it’s so difficult for him to prove to a white world that his people and his ancestors are worth something.

The show relieves tension with the tragic, too-true humor that comes from Leguizamo not knowing how to express himself. He wants to be angry at the state of his people but he’s held back by insecurities. Leguizamo is very self-aware, so that his humor allows him to survive, but his comedy is only a thin cloak hiding his fear that he has failed as a father, as a man and as a Latino.

The show is a 90-minute one-act set in a frantic classroom that becomes more and more disorganized as Leguizamo tries to piece together systematically-forgotten Latin history. His physical comedy helps express his desperate need to prove himself, but the show is underscored by his cheap impressions of (to just name a few) Muslims, Indians, gay men and disabled people, as well as some self-admitted sexism (I, for one, could do with less comedians that apparently hate their wives).

Leguizamo paints a united culture of the Native Americans in North, Central and South America with a blended heritage. He recounts the traditions of the “gentle” Taínos and their rape and slaughter; the great Aztec and Inca empires and their destruction; the civil rights activists, war heroes, judges, artists and creators of culture; and the modern hate crimes, incarceration, immigration policies and bullying. He searches for a way to recreate their dignity. They may have died, but he is still here. Latin people are still here.

While Leguizamo names his goal as giving his son Latin heroes to look up to, it is not hidden from the audience that what he truly needs is to feel validated in his own identity. The classroom setting inverts stereotypes that Leguizamo is otherwise threatened by — he uses a mix of Spanish and English slang to deliver eloquent speeches and mixes Latin dancing and exaggerations of Latin stereotypes to repaint these characteristics as positive.

Audience participation also makes this show unique. It breaches from a long tradition of “The Great White Way,” with audience members calling out in Spanish and English and responding verbally to Leguizamo’s dismay at his heritage being forgotten and that he himself has been “whitewashed.” At one point, he physically rips through his son’s eighth grade history textbook: “not one fucking sentence, not one fucking chapter, not a goddamn mention, as if we’ve been absent all these fucking centuries.”

Leguizamo shares his fear of his past, and his frustration that if he dare be angry, he’ll be dismissed as “ghetto.” He recounts his pleading with his son, “Promise me, man, promise me you’re never gonna lose your shit, especially in an argument, my man. Especially if you’re a person of color, because then nobody hears the content of what you’re trying to say.”

Throughout the show, Leguizamo expresses his feeling that he failed his son — that he did everything to succeed, and it did nothing to stop his son from being mocked for his race. The audience gets to see him break through with humor when he addresses racism with his “ghetto rage,” finally allowing himself to be angry for his people’s erasure, incarceration and illegality in a country they created. And ultimately, the audience sees him find peace and learn from his son that there is a hero in himself.

Leguizamo’s show presents the difficulty in finding dignity when it’s been stripped from you. It is a show that crosses boundaries in the world of Broadway plays, although its sharp racial humor and commentary balances a fine line with racism. Fraught with energy and pain, the show ends with hope that Latin history can be uncovered.

If these 3,000 years of history were in our textbooks, Leguizamo asks, “can you imagine how America would see us? More importantly, can you imagine how we would see ourselves?”