Before Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, there was Hal Ashby. Ashby was an Oscar-winning director and editor who played a huge role in the “New Hollywood” films of the 1970s, including Being There, Shampoo and Harold and Maude. And you’ve probably never heard of him.

Amy Scott’s Hal is an honest portrait of the talented director. She succeeds in telling the story of one of Hollywood’s most mysterious greats and serves his career a bit of necessary justice.

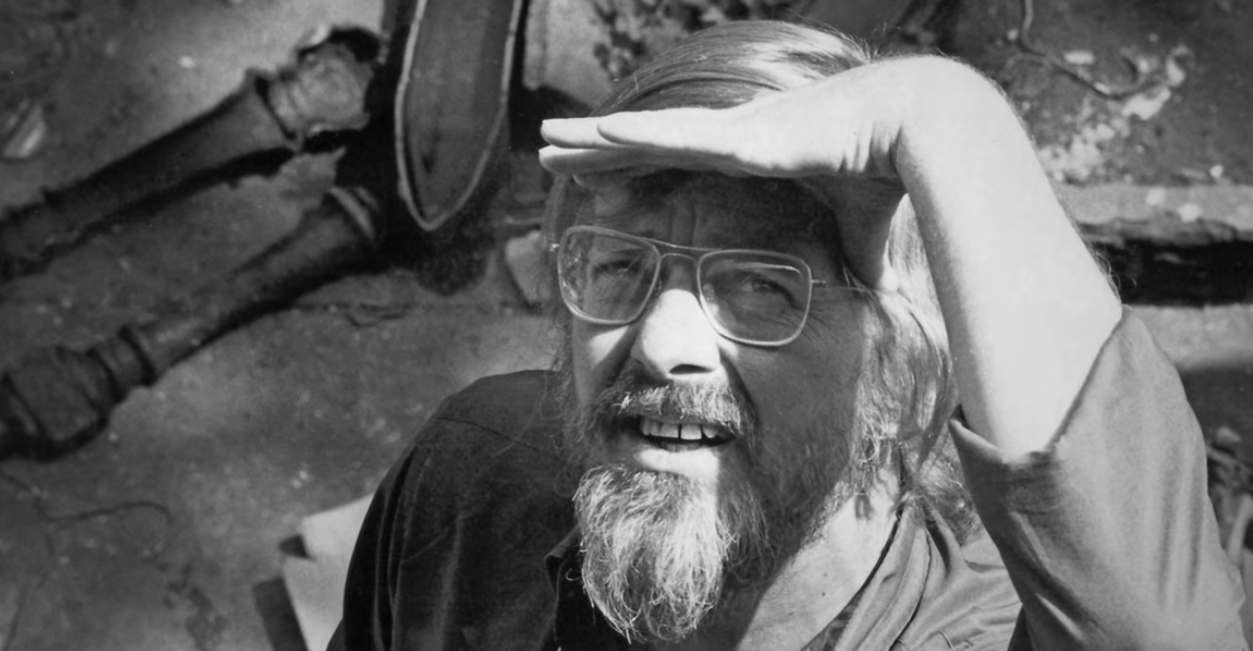

Hal follows the transformation of Ashby’s image from a clean-cut Hollywood hopeful to a shaggy, rugged and unapologetic artist — Ashby’s life was basically one big Hollywood cliché. Ashby’s incredibly rough childhood ended when he became a divorced father before the age of 19. But despite adversity, Ashby went on to work his way up through Hollywood with talent and a bit of luck. He found great success as an editor and director thanks to his gift of expertly portraying experiences of the human condition. His talents were unparalleled for his time.

[Read more: Review: ‘Filmworker’ is a celebration of unsung heroes]

But struggles from Ashby’s past followed him. Despite his brilliance, his genuine films were eventually forced to surrender to the flashy, action-packed products of Hollywood’s new wave of flicks, such as Jaws and Star Wars. After his career declined throughout the 1980s, he died from pancreatic cancer at 59 years old.

Scott does an expert job portraying Ashby’s goodwill through archival footage, personal letters and audio recordings. She depicts his submergence into the hippie subculture of the 1970s as a new Hollywood loomed, pressuring him to do the opposite. It is even possible to argue that Ashby was ahead of his time in his views of equality and social justice — his film The Landlord was considered fairly innovative in American film for its portrayal of race.

Ashby’s distaste for authority and stubbornness forced him into many conflicts with Hollywood higher-ups who oversaw his work. His nearly obsessive need to effect change and provide justice in his films clashed with a business that was beginning to focus more on financial, rather than artistic, value.

[Read more: Review: HBO’s Elvis documentary avoided tough topics and told a tired tale]

People in Hollywood often characterized Ashby as unemployable — or even, toward the end of his career, insane. The newer Hollywood disapproved of his unorthodox concepts and inappropriate language, which is implied to be partially responsible for his career’s decline from brilliance in the 1970s to mediocrity in the following decade. Hal acts as a defense of the director, as Scott depicts the movement against Ashby as a scheme.

Besides creating a biography of Hal Ashby’s life, Scott uses her work as an opportunity to criticize the Hollywood of Ashby’s time as well as the Hollywood of today. The honest stories of the human condition that Ashby fought to create remain a hard sell to today’s Hollywood executives.

Still, Scott does not shy away from portraying the dark, sad side of her subject. She features clips from interviews with a variety of family members and colleagues, all of whom provide different insights into Ashby. His excessive drug use, even by the standards of the ’70s and ’80s, is featured. His womanizing tendencies and failures as a parent are also followed through his five marriages but could have been explored further.

Despite his downfalls, sympathy for Ashby still feels necessary.

Hal is real and transformative, as it truly delivers a 1970s aura through small production details, from the clicking of a typewriter to the bubbly font that’s used throughout the work. It also evokes curiosity for those who were born decades after the rise and fall of his career. Hal is a satisfying narrative and successfully serves the justice it was intended to.

3/4 shells.