By Paige Munshell

Every boy who has waited in line to see Jurassic Park, who has pored through Nineteen Eighty-Four, who has spurned a girl for being a “fake fan,” has one person to thank for the world of science fiction.

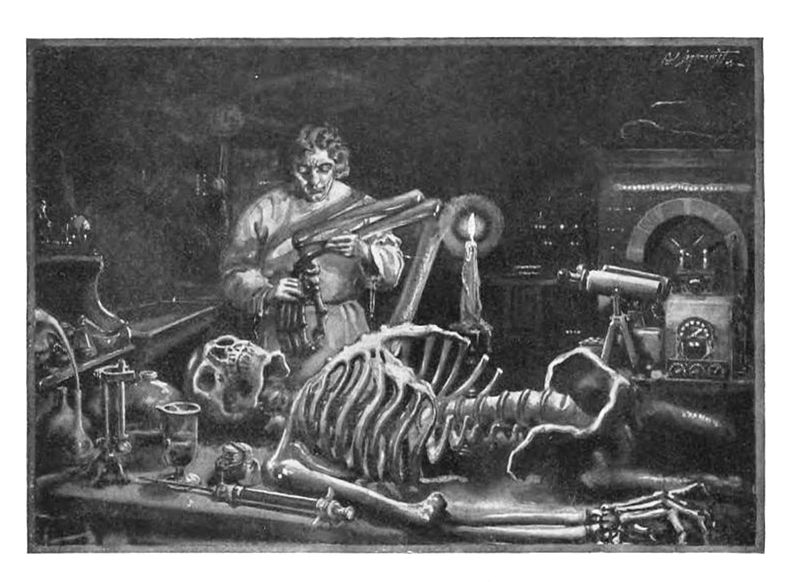

Mary Shelley, daughter of famed feminist philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, is often called the inventor of the genre; Shelley had her debut novel Frankenstein published in 1818, when she was 20 years old.

Now, 200 years later, universities everywhere are recognizing the bicentennial of the publishing. At the heart of Frankenstein‘s monster is a teenage girl without a formal education writing ghost stories to pass the time.

Shelley’s work exhibits the spirit and abilities of young women to influence the world. Every word of the science fiction genre bears Shelley’s influence and the characteristics she brought to life alongside her monster.

Before Jules Verne depicted the frigid, terrifying seascape of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea, Shelley sent Dr. Frankenstein to pursue his creation across the ice and snow, consumed with horror at what he had created.

Before Steven Spielberg asked scientists to “stop to think if they should” in Jurassic Park, Shelley gave us a man so consumed by a passion for science that he lost sight of humanity.

And before Daniel Keyes wrote of devastating loss in Flowers for Algernon, Shelley captured the brilliant and tragic loneliness that accompanies the search for intelligence and human connection.

All of this and more was not in spite of her years as a teenager, but enhanced by them. Shelley experienced a life filled with chaos from the very beginning. While still in her teens, she fell in love with — and later ran away to wed — the already-married poet Percy Shelley.

When she began writing Frankenstein at age 18, she had already lost one child, and would go on to lose two more before being widowed at the age of 24.

Fighting with friends over the ownership of her late husband’s preserved heart (yes, you read that right), Shelley lived out the pain and absurdities of grief that passion and human love create, the elements that embody her work.

Themes of guilt, betrayal, loneliness and self-loathing are central to her seminal gothic novel and have since become trademarks of science fiction. Beyond the most obvious mixture of technology and fantasy, Shelley’s work makes readers ponder deeper questions of humanity.

Shelley’s emotional tale — just a couple hundred pages long — is still reaching audiences in new ways. Children flood the streets at Halloween each year dressed as “Frankenstein,” while their bookish classmates remind them it’s actually “Frankenstein’s Monster” they’ve dressed as.

Adaptation after adaptation hits theaters, drawing crowds with the now-classic depiction of Dr. Frankenstein’s cry, “It’s alive!” and the terrifying groan of a green-skinned monster with bolts in his neck.

Even though these versions have strayed from Shelley’s romantic horror, literature’s original goth girl would love the terror her story continues to provoke.