Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

Screenshots of a temporary eviction notice from the Department of Resident Life went viral in the University of Maryland Twitter community late last week. The letter notified student Faye Barrett that, because she had been voluntarily admitted to a hospital for experiencing a panic attack and taking a high dose of a prescribed muscle relaxer early Thursday morning, she was not allowed to return to her South Campus Commons apartment until she was cleared by a health center psychiatrist and a Resident Life case manager.

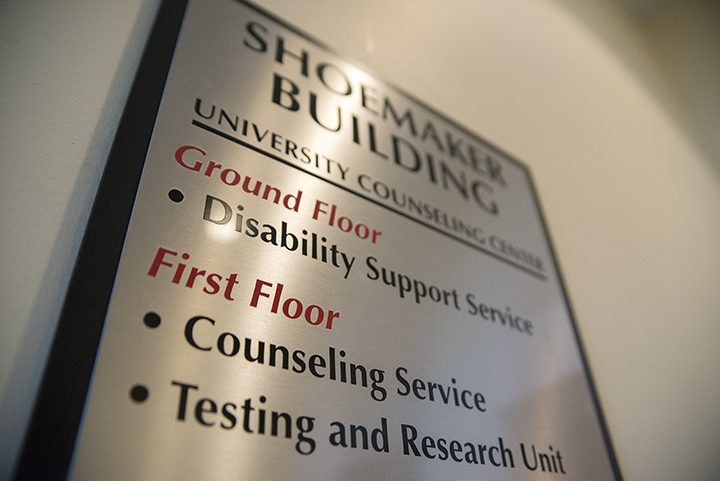

After examining this story, combined with the recent campus discussion about the Counseling Center and the “30 Days Too Late” campaign, it is blatantly clear that this university’s policies and procedures for dealing with these issues exacerbate and enforce a dangerous binary in how we view mental illness.

[Read more: UMD’s Department of Resident Life must show more empathy toward students’ mental health]

People with mental illness face strong dichotomous judgment regarding the perceived severity of their illness. On one hand, people’s struggles are often ignored, minimized and deemed not serious enough to deserve real treatment and action. This happens frequently when someone is not on medication or has not been hospitalized, as their struggles are not outwardly visible to other people. On the other hand, the perceived “true” presence of mental illness is extremely stigmatized, causing the person who has it to be denigrated and sometimes even criminalized. Those who are perceived to truly have a mental illness are feared and shunned, regardless of whether they actually pose a threat.

As the “30 Days Too Late” campaign has noted, wait periods for university counseling can be up to 30 days, unless “[students] are experiencing a mental health crisis.” The director of this university’s Counseling Center wrote that “the Counseling Center provides same-day emergency appointments with a counselor to address the crisis and discuss the best approach for treatment.”

Although same-day crisis counseling is essential, providing either immediate or very delayed care is not in students’ best interest. Neither is the protocol — which Resident Life is forming a committee to re-evaluate — of keeping on-campus housing away from students who have been hospitalized for mental health reasons. Both policies accept the false binary that a person is either entirely healthy or physically threatening. This attitude worsens stigmatization, makes students feel unsafe and lessens the support for students to get help.

[Read more: UMD students deserve timely access to mental health resources]

Being either perfectly healthy or a danger to those around you doesn’t describe the full reality of mental health. This university should not act as such. It’s safe to say that a majority of people who struggle with mental illness are in the middle portion that falls between these two extremes, and the university must recognize that. Not providing help and attention for the majority of people on our campus who need it not only harms the students but also the university itself.

Accepting this false binary is in no one’s best interest. The university needs to take a serious look at how they respond to mental health in our community and implement policies that help and support students who seek help, not punish them for it.

Michela Dwyer is a sophomore English and philosophy major. She can be reached at mgdwyer3@gmail.com.