By Teresa Johnson

For The Diamondback

At the University of Maryland’s fifth Parren J. Mitchell Symposium, students, faculty and local community members learned about social justice issues within racial wealth inequality.

The day-long event, which took place in Stamp Student Union, was part of a series to honor Parren Mitchell, the first black student to take graduate classes at this university. Mitchell received his master’s degree in sociology in 1952 and went on to become Maryland’s first black representative.

The theme of this year’s symposium was racial wealth and equality, said Joey Brown, the event’s organizer and member of the Critical Race Initiative, an on-campus group that seeks to understand inequality in society. Previous symposiums have included topics on racism, health and the media, he said.

[Read more: UMD’s Center for Diversity and Inclusion hosts summit on issues facing college campuses]

The aim of the symposium is to focus on “students who self-identify or are perceived to be in different racial ethnic groups,” and “facilitate education, engagement and encouragement,” Brown said.

“We live in a time where how aware people are of the economic differences between the well-off and the less fortunate have become magnified,” Brown said. “People are just having a hard time in general, and I think this will relate with students … who are coming to school in a capacity to try and enhance their ability to compete in the job market.”

Maria Chen, a junior physiology and neurobiology major, heard about the event from her honors seminar professor. She said she liked how the symposium related to what she is learning about in class, and specifically about “the black, white wealth and achievement gaps and how [both] correlate to impact each other.”

[Read more: Amid uptick in UMD hate bias incidents, officials open campus diversity survey]

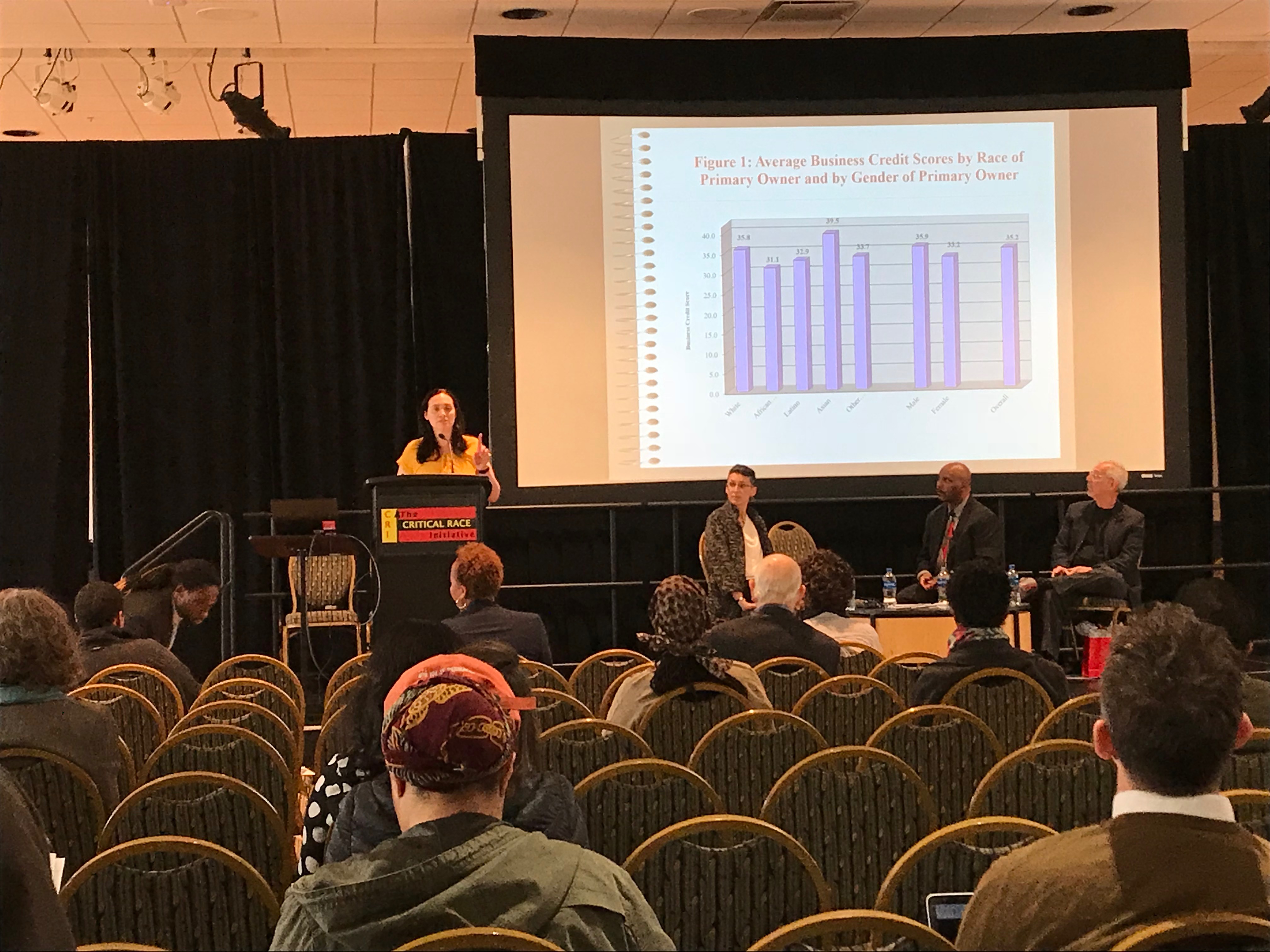

One panel addressed racial and gender differences of wealth inequality and the effect wealth has on minorities.

Panelist Loren Henderson, a sociology professor at this university discussed how credit scores in businesses are inherently biased against minority groups such as blacks and Hispanics.

“The determination of credit for new businesses is not colorblind,” Henderson said. “Perhaps even more disheartening is the idea that even with the same credit scores as whites and men, people of color and women receive significantly less in credit lines.”

In another session, panel speakers covered wealth-building and investing in local communities. The final session sought to find policy solutions to mitigate the racial wealth inequality gap.

“To close the [racial wealth] gap, it has to be through the use of national policies that directly attack the differential, rather than saying black folks have to change their habits,” said panelist William Darity, a public policy and African and African-American studies professor at Duke University.

Ashlyn Bell, a public policy graduate student, came to the symposium because she is interested in how housing policy is tied to wealth.

Bell said she wanted to hear “what we can do to try to close [the racial wealth gap] and steps we can take to educate ourselves.”