“I said I didn’t feel nothing, baby, but I lied/ I almost cut a piece of myself for your life.”

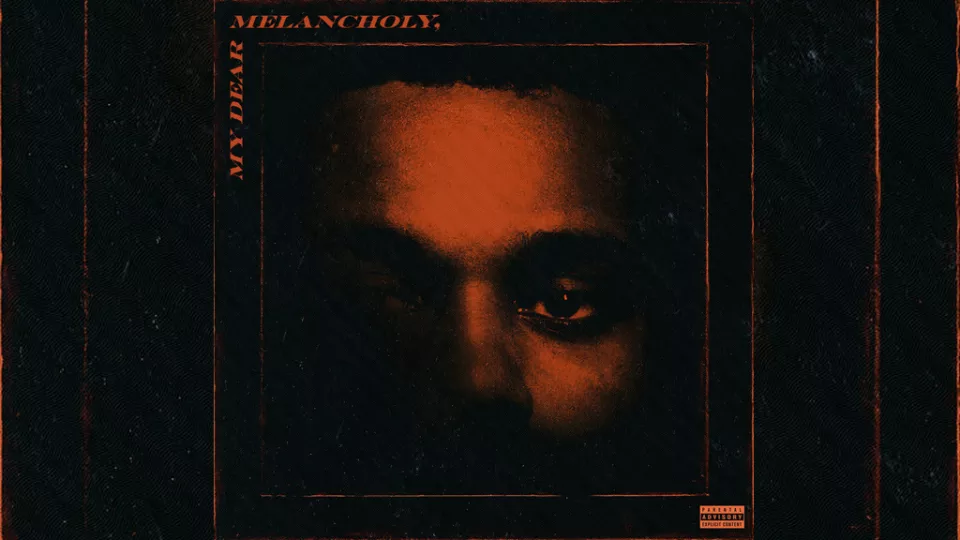

Last summer, Selena Gomez received a new kidney from her best friend, as a result of lupus complications. If fate would have it, her donor could have been her ex-boyfriend The Weeknd, the Toronto singer implies on his latest project, My Dear Melancholy,.

The line, from the EP’s opener “Call Out My Name,” is an impassioned cry that finds the singer returning to his uber-confessional, troubled roots. It’s a perfect showcase of exposition (verse 1), rising action (pre-chorus: “I put you on top, I put you on top/ I claimed you so proud and openly) and climax (the chorus).

In six songs, the 28-year-old magnifies the tumult of heartbreak, a beautiful nightmare with always-meticulous and intimate songwriting and dizzy, wispy production, atypical of his earlier albums — such as Trilogy and Kissland.

“Try Me” is coy and hypnotic, with the singer on the rebound, hungry for getting that old thing back, even though who he sings of has moved on: “Can you try me? try me?/ Once you put your pride aside, You can notify me.” His approach is hard to resist; he knows what he’s doing. At the end, he repeatedly asks “Don’t you miss me baby?”

But he returns much more humbly. “Wasted Times” is a softer track, where he confronts a rare state of mind: remorse, and acknowledges her significance to him. He ends the song with more repetition: “I don’t wanna wake up if you ain’t laying next to me.” Skrillex helps with the production, and there are gentler elements of electronic music, as on the pair of Gesaffelstein features he produced (“Hurt You” and “I Was Never There”).

The former moves on to perhaps the most difficult part of breakups — coping. With his flawless-as-ever falsetto, he equips a cadence similar to the Black Panther soundtrack’s “Pray For Me.” If you listen closely enough, you can also here remnants of the instrumentation of “Starboy.”

“I Was Never There” again closes with repetition. This time, “It’s all because of you.” There are stages to his torture: anger, denial, blame, jealousy (on “Wasted Times”: “And what they got that I ain’t got?/ ‘Cause I got a lot (I got a lot)/ Don’t make me run up on ’em, got me blowin’ up their spot”).

It is only at the end of the project that he begins to venture toward acceptance, a hard pill to swallow. “I got two red pills to take the blues away,” is the chorus of “Privilege,” referencing The Matrix, in which blue pills represent ignorance, and the red one reality. This could be taken literally or figuratively. So while he has not fully recovered, at the very least, he’s reached some quiet after the storm.