A society may well be remembered by how it paints, sculpts and photographs its leaders. When the sands of time erase every last wit of civilization, the shattered visage of Ozymandias will still survey the rolling dunes.

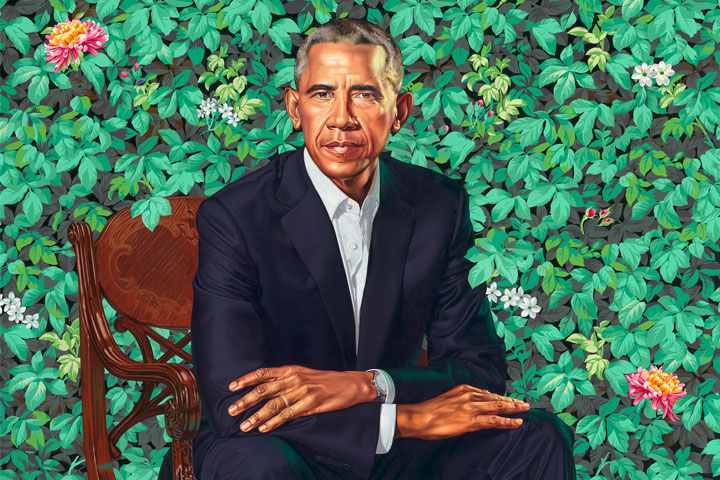

Similarly, one supposes, when climate change brings the banks of the Potomac up Meridian Hill Park, Kehinde Wiley’s newly unveiled portrait of former President Barack Obama will be toted out of the floodplain.

Understandably, then, much has been written about Wiley’s work, as well as Amy Sherald’s portrait of former first lady Michelle Obama, since the National Portrait Gallery unveiled them Monday.

Holland Cotter, the Pulitzer Prize-winning New York Times art critic, wrote in an uninspired and predictable review that beside other recent entrants to “America’s Presidents,” this “present debut is strikingly different.”

He presents a passing nod to Obama’s seat in the Wiley work, comparing it to Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington. “But,” he writes, “art historical references stop there.”

Across the board, critics, commenters and tweeters for — and against — the portrait have pontificated on one aspect in particular: Obama-in-the-Garden is a work singularly without precedent in presidential portraiture.

Indeed, a portrait without precedent parallels the presidency it portrays. Rightly so, the work is historic and unique as the first of a black president and first lady, painted for the first time by black artists to boot. And there is a whole lot of artistic innovation in the works.

But entirely without reference or precursor? Not quite.

Beyond the intrinsic role of history and art history on all new work, there is a key precedent in presidential portraiture to Obama-in-the-Garden, and it hangs just a few walls away in that cavernous gallery in Washington, D.C.

Elaine de Kooning’s 1963 portrait of John F. Kennedy. (Elaine de Kooning/Image courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery)

As 1962 waned and ’63 crept up gingerly behind it, painter Elaine de Kooning traveled to temperate Palm Beach, Florida, to paint President John F. Kennedy.

A prominent Abstract Expressionist and the wife of an equally prominent one, de Kooning won the Truman Library commission, so she wrote for ArtNews in 1964, in part because of her frenetic style that usually required just one sitting.

Kennedy threw a rod into her process, a man “always in action at rest,” she wrote. Instead, she worked from sketches, and the portrait consumed her for a year as she created 23 paintings of the first Catholic president until his 1963 assassination abruptly halted her output.

The result was something unlike any presidential portrait before.

“We’re talking here about two artists who do not approach portraiture in an academic, traditional way, but who are invested in approaching it with a fresh look,” Taína Caragol, the curator who worked with Obama and Wiley, said Tuesday.

Both artists were “pushing the boundaries of contemporary portraiture … in their particular time,” Chief Curator Brandon Brame Fortune agreed. “De Kooning was doing portraits that were considered to be really out there: They were gestural, they were colorful, they were large. And, of course, Kehinde Wiley is also.”

(In fairness, Cotter does mention the famous de Kooning work in his review, as a welcomed respite from the dreariness he sees in the “America’s Presidents” exhibition. But he doesn’t compare Wiley’s work to de Kooning, going so far as to write that it lacks “tonal echoes of past portraits.”)

The similarities between the two works are striking but unobtrusive. Both presidents pose casually, leaning in, looking at us. Both feature presidents who broke molds, although subject comparison in portraiture is a long fruitless exercise.

Both backgrounds are flat and abstracted through layers upon layers of interacting color, and, most obviously, both are green.

In de Kooning’s, broad brushstrokes of emerald cascade over patches of yellow as areas of forest green, sky blue, orange and mauve define Kennedy’s edges. Behind it all is the white of canvas.

Wiley’s is more polished but similarly abstracted. His leaves, upon close looking, appear stenciled, not rendered. They layer up from a background of pure black to brown, grey and olive roughage then sage, mint and teal leaves with lime-green and cream at the fore. Obama neither penetrates nor is covered by the greenery, instead interacting paradoxically behind and before the leafy wallpaper, a trope in Wiley’s other work.

“The setting in Kehinde Wiley’s painting, that beautiful foliage and symbolic flowers, is meant to reference what the artist does best but to give a very rich and contemporary look to the painting,” Fortune said. “And Elaine de Kooning is of course reflecting the green and the vibrancy that she found in Florida.”

The question then turns, as it so often does, to why. Why do curators, critics and Wiley alike insist the work exists in a vacuum, even with such a clear example that proves it doesn’t?

For one, the work is very new. It’s hard to effectively draw lines between works so quickly, and harder still to do so without minimizing the newer artist’s creativity, genius and merit — never the intention herein.

But there is something more pernicious at work.

The work is considered independent of canon for the same persistent reason that artists of color are too often excluded from the annals of American art and pigeonholed among themselves.

Sometimes, this lets us elevate the marginalized artist’s voice independent of a stifling white art history. But in scenarios where works interact cross-culturally, as they now do in “America’s Presidents” for the first time, this separation can be distractingly othering.

Luckily, the issue is forced. Obama was president, and his portrait will hang in Washington, D.C. ’til the end of our republic — even if critics are initially reluctant to view it how they should.

Thoughtful discussion of Wiley’s place in the pantheon of presidential portraitists will follow in time.

Obama-in-the-Garden becomes part of how we paint our leaders, a pursuit we still haven’t perfected as America enters its fourth ordinal century.

And it doesn’t get any more canonical than that.