Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

I truly hate that my views on freedom of speech place me on the right wing. On nearly every other issue, I swing further left than a right-handed batter trying to pull the ball (as my woebegone conservative friends will tell you). But with free speech, whether evidence of some dormant libertarian streak or a side effect of my journalism education, I flip.

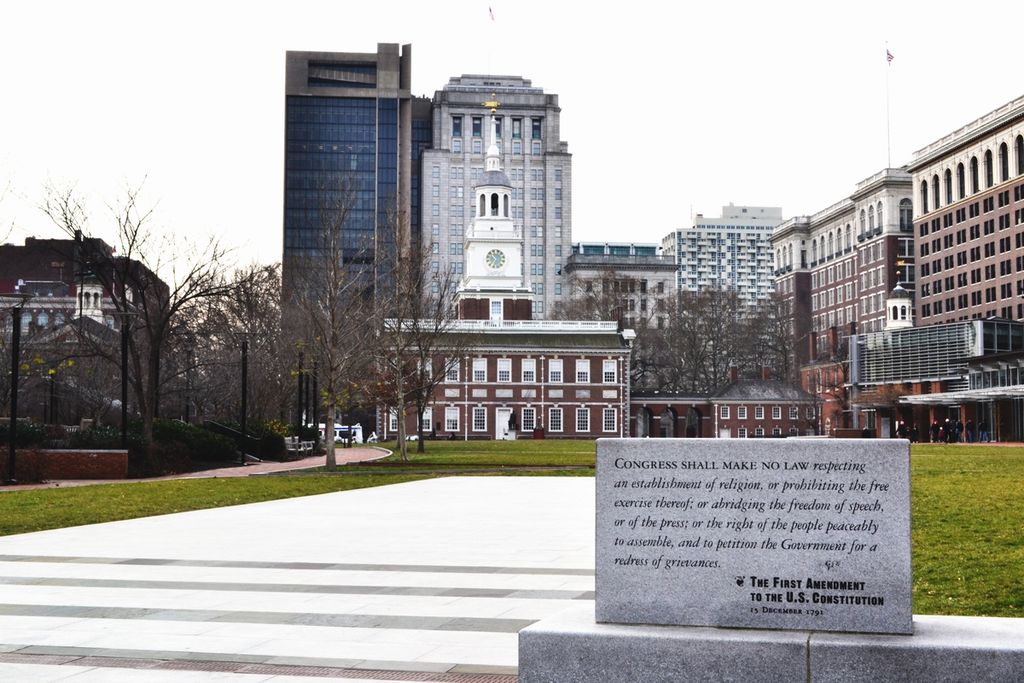

Indeed, the press and the right wing are strange bedfellows. While President Trump and his fans hurl insults at the news media, and the news media hurl hard-hitting journalism back, the two both depend on a hard-line interpretation of the First Amendment. I believe that blanket freedom of speech is the single greatest accomplishment of post-Enlightenment human thought. The idea that a person, no matter his or her station, can say whatever he or she wants without fear of government reprisal is beautiful — and of paramount importance.

So, when I saw a column by my Diamondback colleague Moshe Klein titled “Colleges should only prevent speech that makes students feel unsafe,” I nearly choked on my iced coffee.

Colleges should almost never prevent speech, even if it does make students feel unsafe. Constitutionally speaking, this is nearly absolute. However, in a debate with so much confusion, it is important not to sully our discourse by resorting to ultimatums.

First of all, we must inspect whom the First Amendment’s prohibition applies to: “Congress,” and by established extension, any organ of federal, state or local government, including this university. Second, we must establish what it protects. Barring a stunning change in precedent, it protects all speech, written and verbal, with the exception of libel, slander, fighting words, obscenity, child pornography, perjury, blackmail, incitement, copyright infringement, criminal solicitation, true threats and perhaps treason, according to a list compiled by the Newseum. Precedent also dictates the First Amendment covers speech uttered by all people in the United States, citizen or not.

Thus, when Klein asks, in his opening paragraph, “Where does free speech end and offensive rhetoric begin?,” he introduces a false syllogism. Offensive rhetoric is constitutionally protected free speech. Free speech ends far past it.

At the midpoint, where speech is simultaneously offensive and legally protected, some of the far right’s seedier factions begin spewing disgusting slurs, vulgarities and offenses. At this point, you no longer want to defend the speech, as you see the pain it brings to those groups and individuals it targets.

This is because it is here where moral speech deviates from legally protected speech. People should not say things that make the people around them feel unsafe. They should not hurl racist, sexist, homophobic, transphobic, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic or any other demographically pointed insult at one another.

Morally, these things are wrong. Full stop wrong. But in a purely legal sense, they are permissible. And when weighing what is more important — an unfettered ability to voice opinions or a place where speech is limited yet conversations less destructive — I will side with pure free speech each time. This freedom is too important to regulate beyond the bare minimum, even if entrusted to the most considerate government. The road to fascism is paved with good intentions.

The left, at this juncture, becomes far more dangerous to free speech and press than the media-bashing right ever does. Liberals seem to suggest small speech regulations here and there, to curtail expression that is most likely repugnant. Bans on slurs in sports teams’ names, perhaps, or prohibitions against currently protected hate speech in certain venues.

Some look at countries like France — which banned news outlets from reporting the details of hacked documents related to then-presidential candidate Emmanuel Macron — and wonder whether a similar stopper could have been placed on American media regarding Hillary Clinton’s emails. Because the left can use Trump’s anti-media rhetoric as a foil, it can obscure some of its ideas as sensible, when in fact they undermine press freedom far more perniciously than a GIF of the president clocking CNN.

Yet while the left is too quick to weigh abridging freedoms, the right is too quick to claim their rights are being violated. This is especially evident in the college speaker debate Klein focuses on. Let’s take it back to the college level and be very clear about what does and does not violate the First Amendment rights of, say, a controversial speaker.

A public or private university itself not inviting or disinviting a speaker does not violate that speaker’s free speech. The speaker has a right to speech, not a platform.

A private university banning a club from hosting a speaker does not violate that speaker’s free speech. Private schools are not extensions of Congress.

A public university banning a club from hosting a speaker doesn’t violate that speaker’s rights, either — in reality, it violates the hosting club’s First Amendment protections. See points one and two for why.

Student demonstrators protesting or disrupting an impromptu or club- or university-hosted speech does not violate anyone’s free speech. Those protesters are not extensions of Congress, either.

In his column, Klein argues that a university ought to screen speakers, though he commendably cautions that the policies not go too far. He says it’s important to ensure people feel safe when speakers appear.

I am not in the demographic that is likely to face harassment and speakers who tacitly threaten me, so far be it for me to tell anyone what should or shouldn’t offend. But, as painful as it is to say, being offended — even feeling unsafe — doesn’t hold legal water.

I’m not some brash conservative asshole calling protesters snowflakes without strong character or arguing that offensive speakers contribute to a marketplace of ideas on the campus. That is, frankly, placating bullshit promulgated by university administrations to mask the fact that their hands are tied by constitutional law and wealthy conservative donors. Your feelings are valid, you’re not a snowflake and I don’t think Ann Coulter or Milo Yiannopoulos have much to add to our marketplace of ideas anyhow.

But that’s not what matters.

To avoid a fascist dictator stronger than Donald Trump fancies himself in dreamland, these nutjobs must be allowed to spew their hate. Their freedom to do so outweighs any other concern.

Evan Berkowitz is a senior journalism and art history major. He is the Diamondback’s design editor. He can be reached at evanjberkowitz@gmail.com.