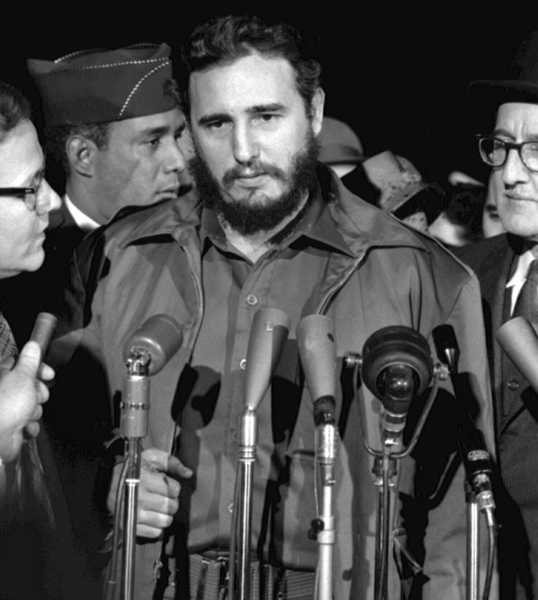

For news publications, the convenient thing about Fidel Castro’s death is that they’ve had the obituary ready for 45 years. Cuba’s fiery revolutionary and survivor of innumerable CIA assassination attempts, has passed away at 90 after a long stretch of declining health.

In the United States, his name is often synonymous with the cauldron of political tensions following the communist revolution. The reality, of course, is more complex. Castro was many things — a political radical, a shrewd image-maker, a power-wrangler — but more importantly, he was a dealer in the currency of hope. After six war-torn years in the mid-1950s, Castro seized power as a socialist, promising to drive out American influences and stamp out corruption while ushering in a new day of Cuban solidarity and unity.

The results of his nearly 50-year rule were ultimately a mixed bag. Castro did indeed turn Cuba from a playground for wealthy Americans into a sovereign nation. Medical care was made freely available to all Cubans. Infant mortality rates plummeted. Excellent education became very attainable — in fact, Cuba exports doctors to the rest of the world. At the infamous Bay of Pigs Invasion, he landed a counterpunch against the international reach of the indomitable United States.

Concurrently, his rule has been rightly condemned for a series of human rights abuses against his own people — extrajudicial execution, a total absence of due process, torture and censorship. The human cost of Castro’s repressive political stranglehold defies statistics. In 1998, Pope John Paul II condemned Castro. It’s perhaps unsurprising, then, that early accounts after his death have pegged the mood in Miami’s Little Havana as celebratory, as Cuban expatriates proclaim “¡Cuba si! ¡Castro no!”.

It is now a time of transition for Cuba. The reestablishment of an economic relationship between Cuba and the United States has implications for millions of poor Cubans who find themselves suddenly brought into the 21st century. Decades of Cuban isolationism, spurred on by Castro’s cries that Cuba “needs nothing” from the United States, have now cracked open. Perhaps el máximo líder — Cuba’s maximum leader — himself had begun to thaw, saying in 2010, “The Cuban model doesn’t work any more — not even for us.”

For many Cubans, the links between the U.S. and their nation are simply too strong to will away with Cold War isolationism. Too many families are split between the two countries and there is too much to be gained from an economic relationship. Castro himself welcomed the thaw in tensions, calling it “a positive move for peace in the region.” Perhaps most importantly, it happened with nary a pistol in sight.

Castro was a revolutionary and a tyrant, a symbol of hope and a symbol of repression. His passing leaves behind a country quick to acknowledge his historical import, but ready to bid farewell and move on from what he represented.

Jack Siglin is a senior physiology and neurobiology major. He can be reached at jsiglindbk@gmail.com.