By Alyson Kay

For The Diamondback

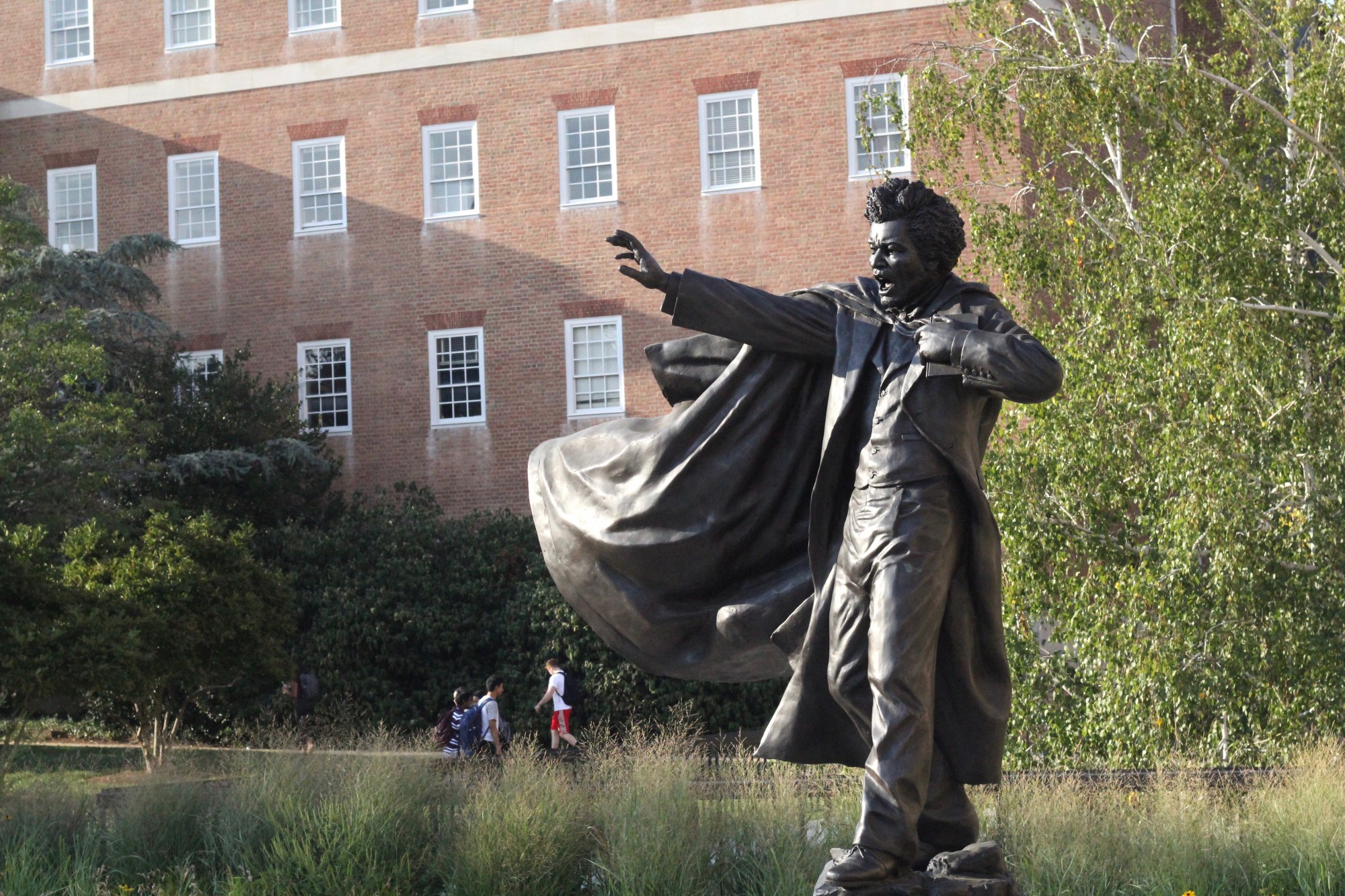

Outside of Hornbake Library, there stands a 7-and-a-half-foot-tall, bronze statue depicting Frederick Douglass mid-speech.

But inside the library, there’s an exhibit that digs into Douglass’ life before he became a famous orator – when he was a slave at Maryland’s Wye House, seven miles outside of Easton.

About 150 people have visited the exhibit since September, according to University archivist Anne Turkos. She said she hopes people come away with “a deeper appreciation of what life was like as a slave at Wye House in particular, and in Maryland and the Mid-Atlantic region in general.”

Through nearly a decade of excavating the Wye House, University of Maryland archaeologists discovered many artifacts, which will be on display in Hornbake Library through July.

The archaeologists sought to find evidence of how slaves influenced Maryland culture.

The artifacts reveal how both slaves and slave owners made food on the Lloyd’s plantation. Two cookbooks show that a mix of African American women and Lloyd women thought out, wrote and cooked the recipes.

There is also a detailed census on display at the exhibit, which was used to record each of the slaves’ names. Though the census is opened to just two pages, it gives a sense of how many people were enslaved on the property.

In 1840, 168 slaves lived on the Wye House Farm. Next to each name, a monetary value is listed.

Doctoral candidate Tracy Jenkins said the Lloyds took two unusual steps in managing their large group of slaves.

“First, the recording of censuses at all, so they could more effectively manage their plantations,” Jenkins said, “and second the inclusion of last names, which might have had to do with managing hundreds of slaves, some of which might have had the same first name.”

The exhibit also features a video interview with one of the descendants of a former Wye House slave. Harriette Lowery is the great-granddaughter of Agnes Demby Green, who is one of the people Douglass mentions in his autobiography when he recalls the brutal conditions on the plantation.

In his book, Douglass writes about a slave named Demby who was killed by an overseer after refusing to get out of a creek after being whipped.

In the video, Lowery talks about how upsetting it is to know that one of her ancestors was murdered at Wye House.

But she also spoke of how the researchers included her and the descendants of the slaves in the research. Lowery said in the interview she was impressed by the “openness” the researchers showed in giving the descendants of people enslaved at Wye House a chance to learn about the history of their ancestors.

University archaeologist Mark Leone said the excavation of the Wye House is not the end of the team’s work. He said they’ll continue to work with African American communities in the area to excavate sites “they consider central to the preservation of their identity.”

“We have finished our work [around Wye House].” Leone said. “Now, we continue to excavate nearby Easton itself.”