By Julia Reed

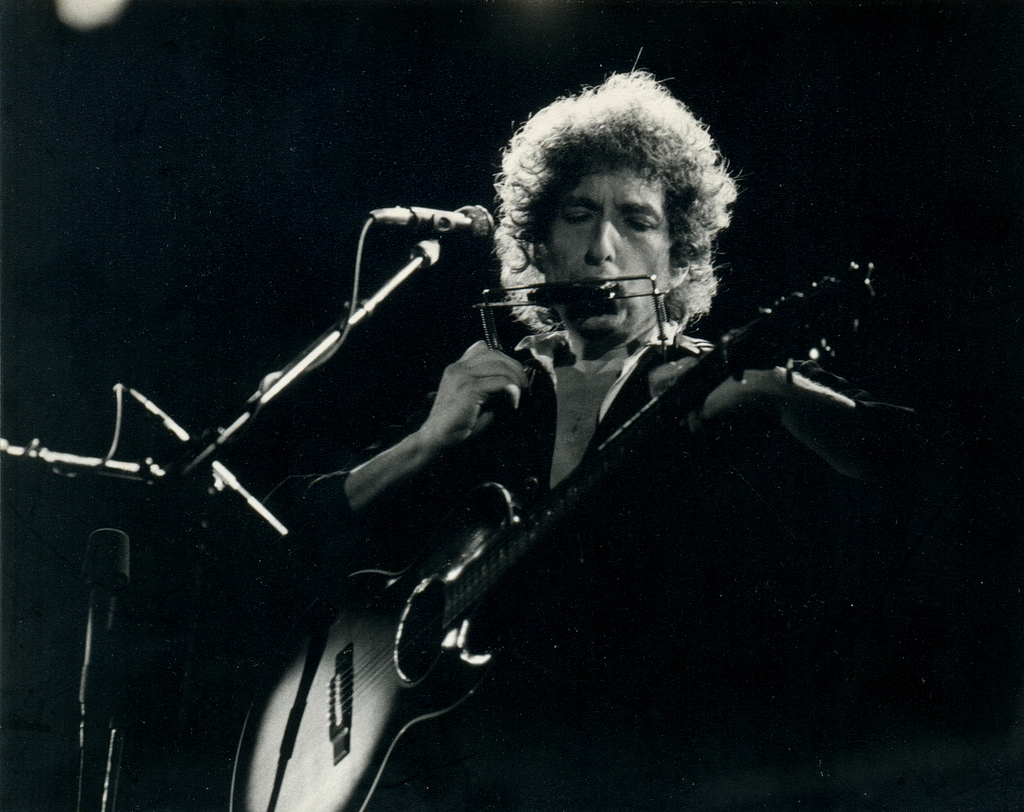

In the summer of 2013, I dragged a lawn chair outside Merriweather Post Pavilion in response to one of history’s most famous requests:

“Come gather ’round people. Whereever you roam,” singer-songwriter Bob Dylan sang.

My father refused to buy tickets, claiming we would essentially get the same experience by sitting along the perimeters of the outdoor venue. So, without a ticket, I sat outside and waited to hear a man weathered by age play “Forever Young.”

To this day I still don’t know if he actually did play it. The only song I could understand was “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall” which sounded more like “A haaaaaar rainagonnafaa.” He was 72 then, what did I expect?

“Ah, but I was so much older then, I’m younger than that now.”

It’s hard to believe that a 23-year-old Bob Dylan sang that lyric in 1964. Now 75 years old, he has been awarded the Nobel Prize in literature. Dylan is the first musician to win the award.

The Swedish Academy awarded Dylan the prize “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.”

Dylan’s influence is unparalleled by any American artist of his time — a time when the music landscape was flooded with British musicians. To the protest movement, he had a level of credibility unmatched by any Brit. His songs were rooted in American soil.

He was a poet-historian hybrid of the ’60s. Many of his songs were news articles set to a rhythm; songs such as “Hurricane” or “The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll” that detailed cases of injustice, used quotes, characters and analysis. He was the songwriter of U.S. history.

For every dated song, Dylan wrote a timeless one. “The Times They Are A-Changin'” captured the sentiment of an era and simultaneously remains ageless to this day. Cases such as Rubin “Hurricane” Carter or Hattie Carroll may be in America’s past, but the times will always be changing and new ideas will always challenge society to swim or sink like a stone. The song, full of verses that withstand expiration, will always be relevant because “the present now will later be past” is an infinite reality.

There is no doubting Dylan’s historical significance, but the Swedish Academy’s decision has received some pushback since its announcement Oct. 13.

Perhaps it is Dylan’s abundance of music that gives the skeptics ammunition. How can this twangy Dr. Seuss win the Nobel Prize in Literature with lines like, “A fish that walks and a dog that talks”?

Even I question why Dylan’s “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” is seven minutes long when three minutes would have been sufficient. Instrumentally the song repeats the same thing nine times, yet the story pulls you through. I feel like it’s some weird alternative Canterbury Tales prologue. With the ragman, the senator, Mona, the preacher, the rainman, even Shakespeare. At the end of each stanza he asks, “Oh Mama, can this really be the end?” and it’s not the end. I don’t understand everything Dylan writes, but I could easily say the same thing about John Steinbeck, also a Nobel Prize winner.

Jokes aside, Dylan is the Faulkner of folk. He spares not a single detail, rhyme or inflection in his songwriting. A magnificent 11 minutes and 21 seconds long, “Desolation Row” is an example of the songwriter’s unconventional style. This song, difficult as any Advanced Placement English passage to decipher, is just one reason Dylan is eligible to win the Nobel Prize in Literature as a musician.

Should more musicians be considered for the award? Perhaps. The line that separates musicians from writers is typically gray. Dylan is different. He is, without a doubt, more of a writer than musician. His skill with the harmonica has more to do with timing than technique. The harmonica breaks are always timed perfectly and follow stanzas that warrant reflection.

“Yes, and how many years can a mountain exist

Before it’s washed to the sea?

Yes, and how many years can some people exist

Before they’re allowed to be free?

Yes, and how many times can a man turn his head

And pretend that he just doesn’t see?

The answer, my friend, is blowin’ in the wind

The answer is blowin’ in the wind”

It’s as if the harmonica’s purpose is to allow a moment to ponder the series of rhetorical questions. “Blowin’ In The Wind” was an iconic protest anthem during the Civil Rights Movement, a movement Dylan was part of until he backed away from politics, feeling that his preaching had become phony. Dylan’s opinions on politics waned down since then. His response to winning the Nobel Prize in Literature follows this trend — it’s minimal.

Dylan may never say how he truly feels about winning the award. Perhaps he believes folk isn’t literature at all. But folk is for the people. It’s a genre of music, where words are more important than chords and meaning trumps technique. Not every musician is a writer, but not every musician is Dylan.

“Well, I try my best

To be just like I am

But everybody wants you

To be just like them”

Dylan is how he is, and how he is deserves the Nobel Prize in Literature.