After passing a special training program, University of Maryland Police officers are prepared to combat heroin and other opioid overdoses.

The training teaches officers to administer Narcan — a drug that competes for the same receptor in the body that opiates attach to, reversing the effect of an overdose, said Capt. Ken Ecker, emergency manager for University Police.

When opiates such as heroin enter the body they attach to receptors in the brain, providing a calming effect and reduced breathing rate, Ecker said. During an overdose, however, breathing slows drastically and bodily functions begin to shut down — almost causing a victim to go into a coma, Ecker said.

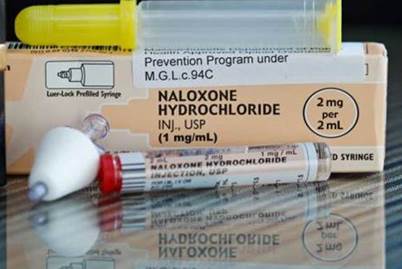

The Food and Drug Administration approved the nasal spray version of Naloxone hydrochloride, or Narcan, in November 2015, according to an FDA news release.

“Narcan removes opiates from receptors, allowing organs to start working again,” Ecker said.

Though opiate overdoses are not a problem on the campus, heroin and opiate-related deaths have risen annually since 2011 in the state of Maryland, Ecker said. Taking note of this upward trend, University Police Chief David Mitchell initiated Narcan training as a preemptive step, ensuring his officers are ready in the event of an emergency.

In Maryland, heroin-related deaths rose from 238 in 2010 to 748 in 2015, according to the state’s Department of Health and Hygiene. From 2014 to 2015 alone, heroin deaths jumped by 170.

“Chief Mitchell decided that basically, if there’s something out there that can better prepare our officers to help the community in case something like [a heroin overdose] happens … there’s no reason that we shouldn’t carry it,” Ecker said.

The trainings are a joint effort between University Police and the University Health Center, Ecker said.

In fall 2015, Ecker, along with five other officers, were trained by the Prince George’s County Health Department to become certified instructors of the drug’s administration, said police spokeswoman Sgt. Rosanne Hoaas. Ecker then trained some of the staff, pharmacists and doctors at the health center so they would also be prepared to answer questions about the drug.

“If a student, parent, faculty or staff were to ask either an officer or somebody within the health center staff questions about Narcan and either what it does or how to administer it, we would all be saying the same identical thing,” Ecker said.

Forty-one officers were trained to administer Narcan on Sept. 16, and other officers will be trained throughout the semester, Ecker added. The majority are patrol officers, who would likely be first on the scene in the event of an opiate overdose.

“[The training] is basically just another element added to our first-responder training, which we learned in the academy and are constantly retrained on,” said officer Brian Naecker, who completed the training earlier this semester. “[The Narcan] now is another tool we can use as a first-responder.”

Naecker also said that for himself and many other patrol officers, this was their first time learning about opiate overdoses in a training-type setting. Participants were taught about the signs and symptoms of an opiate overdose, as well as how to properly respond and administer Narcan, he said.

Narcan, which is injected nasally, is an effective treatment for both pharmaceutical and synthetic opiates, Ecker said. It’s safe enough to give to both pregnant women and children, and has no adverse effects — even if there are no opiates in the body, he added.

In the past, officers were only certified to provide CPR for an overdosing individual while waiting for Emergency Medical Services to arrive, Ecker said. However, now that officers are able to carry and utilize Narcan, University Police are equipped to take more effective action.

Although the health center also keeps Narcan on hand, they have never had to use it, health center director David McBride wrote in an email. An opiate overdose typically causes a person to “drop” wherever they used the drug, making immediate on-site care a critical step to saving a victim’s life.

“The UMPD are in the field responding to incidents,” McBride wrote. “It is unlikely that a person would walk into the [health center] with an overdose.”