By Nathaniel Harold

For The Diamondback

The University Health Center sent an email earlier this month informing the campus about the Zika virus. In Maryland, there have been at least 85 identified infections, the email said, all of which were contracted during travel.

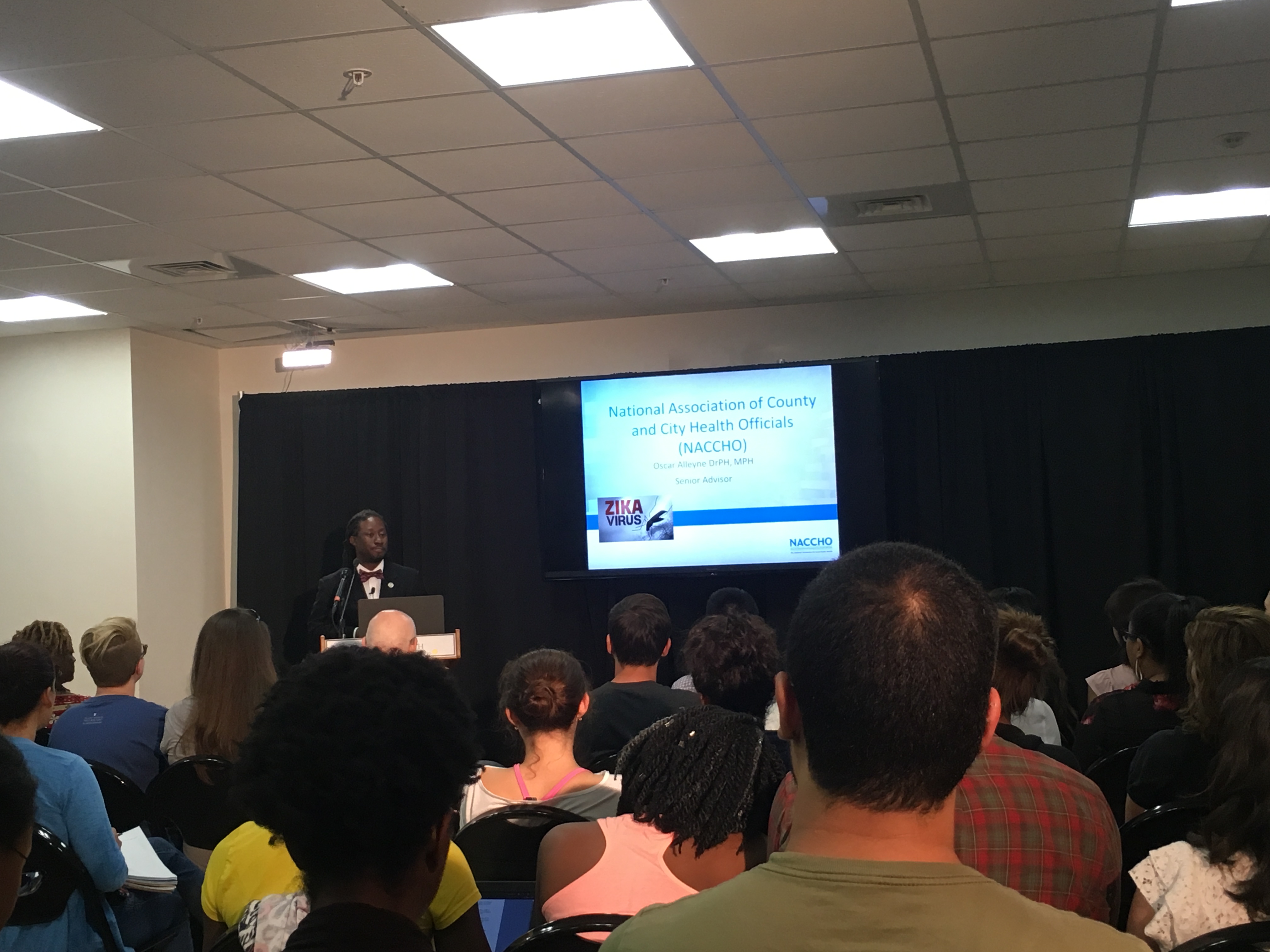

On Thursday, Oscar Alleyne, the senior advisor of the Public Health Program for the National Association of County and City Health Officials, spoke to a group of more than 80 students and faculty about how he and other health officials have worked to combat the virus.

“Dr. Alleyne is not only a dynamic person who can bring that real-life experience to our school, but he is also a role model for many African-American and minority students,” said epidemiology and biostatistics professor Olivia Carter-Pokras, who also serves as associate dean for diversity and inclusion in the public health school’s epidemiology and biostatistics department.

Alleyne stressed the importance of communication among public health officials.

His speech, titled “Responding To Zika: An Epidemiologist’s Perspective,” focused on his work as a public health official attempting to fight the Zika virus.

Alleyne said disease epidemics occurring outside the U.S., such as Zika, are exacerbated as the world becomes increasingly interconnected.

“Global health risks are continuing to rise,” Alleyne said. “The impacts of things that happen on one side of the hemisphere impact us here in our daily lives.”

He also discussed how poor communication and leadership skills among public health officials have made it difficult to effectively combat Zika and similar diseases.

While the responsibilities of handling disease epidemics usually fall on local health departments, they are often not equipped – in terms of both funding and personnel – to handle health issues of that magnitude.

Alleyne said increased cooperation between local, state and federal health agencies is necessary to improve these conditions.

Local health departments must train epidemiologists to have leadership, management and media relations skills, he said, and not just allow them to works as scientists.

“It isn’t the absence of microcephaly [epidemiologists should be concerned with], it’s what we are doing on a day-to-day basis to address the health and protect the health of those whom we serve,” he said.

The lecture, which was held in the Friedgen Family Student Lounge in the public health school, was a part of the Public Health Grand Rounds series.

“As you know, the Zika epidemic is of great public health import both domestically and globally,” said Typhanye Dyer, an epidemiology and biostatistics professor. “As such, we have a lot of questions from students about burgeoning or emerging epidemics in this country.”

Steven Sheridan, a graduate student studying public health, said it was helpful to see how theories learned in class can be applied to the real world.

“In order for epidemiology and public health to work,” Sheridan said, “we need to be able to communicate the findings that we make as well as collaborate on the local, state and federal levels.”