ELKTON Every day university freshman Charlotte Sanford-Crane’s little brother, Isaac, 10, combs through stacks of hay looking for fresh brown eggs. He sifts carefully through the various chicken coops on his parents’ 13.5-acre farm in Elkton – a small, modest “hobby farm” as described by their mother, Liza.

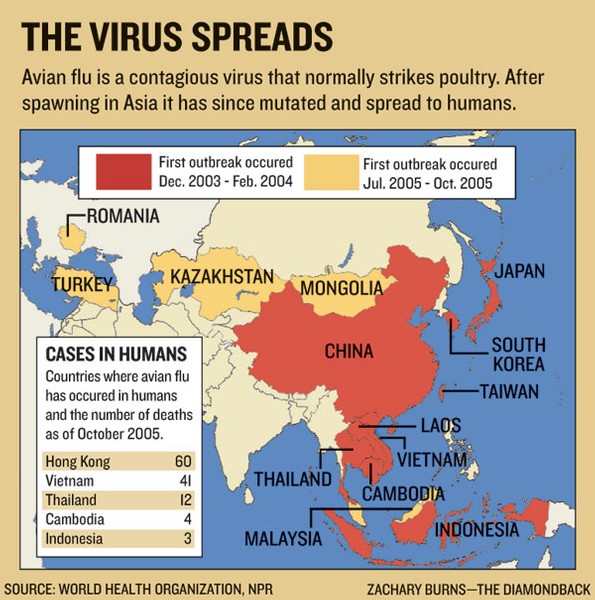

A couple dozen chickens, a few turkeys, a flock of geese, some peacocks and three emus – all potentially susceptible to a new strain of avian flu that is popping up across Asia and Eastern Europe.

While the threat of avian flu remains on the other side of the globe, its impact has reached the university community.

From a student’s small family farm to a poultry farmer’s 80,000-strong flock to one university researcher who potentially has the resources to get to the bottom of all this – avian flu has made its significance known in Maryland.

Despite the deadly virus’ potential, the Sanford-Cranes aren’t too worried. They buy their chickens from Murray McMurray Hatcheries which vaccinates against certain diseases. Liza Sanford-Crane’s only slight concern was for wild geese that mingle with her flock in their backyard pond.

Her concerns are not unfounded given that the virus originally showed up in Europe because of migratory patterns of wild birds that contracted the H5N1 strain from poultry in southeast Asia, said Daniel Perez, a university researcher. Perez, who oversees a $5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, studies how the virus spreads and potential cures.

For Perez, the grant his team received nine months ago now has greater meaning. The desire to obtain Perez’s expertise has spiked in recent weeks, with major media such as CNN, C-SPAN and Univision (Perez is bilingual) leaving messages on his campus phone.

“I haven’t been able to call all of them back,” he said Saturday.

In his lab, Perez and colleagues manipulate genes in ducks, chickens and quail infected by a milder avian influenza strain, which still allows him to study the habits of the virus. Perez’s lab is working with companies like Synbiotics to find ways to diagnose bird flu. They are also looking for the best ways to vaccinate against infection.

“The idea is very simple,” Perez said. “If you can prevent [the virus] in one species, you can prevent it in humans.”

For humans, the avian strain’s ability to recombine its genetic makeup with that of a human influenza strain could lead to a pandemic.

On the Sanford-Crane farm, the family’s immediate concern is to ensure Charlotte’s beloved peacocks, Isaac’s egg-layers, and the family’s hobby farm can stay intact.

In nearby Queen Anne’s County, however, a different mood dominates the massive poultry farm operation of Jennifer Rhodes, a coordinator for the Maryland Cooperative Extension, an organization run partly through the university’s College of Agriculture and Natural Resources that provides information to local farmers. Her 80,000 chickens are kept on lockdown and are subject to weekly check-ups from parent companies that purchase the birds.

“[The chicken business] makes my mortgage payments … It could be very devastating,” said Rhodes.

Rhodes involvement with the Maryland Cooperative Extension marks active steps taken on the part of the farming community to keep its constituents informed about the virus. A website full of resources and even demonstrations on the proper techniques to dispose of diseased birds are among some of the services that the group provides to local farmers.

Unlike the informal trips through the Sanford-Crane farm, even members of the media are kept far from Rhodes’ poultry houses for fear of infection.

An infection found in the flock could mean an immediate quarantine of the entire farm, the slaughter of all poultry and eventual composting of the birds, said Dr. Nick Zimmerman, an associate professor in the Animal and Avian Sciences department.

For farmers like Rhodes, the implications of such a wipeout could mean a massive loss of income.

“You can bet everyone who grows chickens out in Eastern Shore is afraid from a business standpoint,” Zimmerman said.

Right now, the counterparts of Maryland farmers in Romania, Greece and elsewhere are struggling with euthanizing large flocks and keeping a cautious eye on the potential human toll of the virus.

Fortunately for Americans, the Atlantic Ocean serves as a large buffer – a barrier of protection that can only be overcome by human or feathered carrier.

Meanwhile, as scientists and farmers hope that day never comes, in Elkton young Isaac will continue to forage for eggs not knowing that the diseases’ arrival to the states remains a point of contention.

“It’s the 1 million dollar question,” Perez said. “It may happen today or never happen.”

Contact reporters Tom Howell and Will Skowronski at howelldbk@gmail.com.

A closeup view of the H5NI strain of the avian or “bird flu” virus.