The story of race in this country — and at this university — is neither pretty nor neat.

Since 1856, this university has played host to some of this country’s most groundbreaking strides in overcoming racial divides in sports. Terrapins football player Darryl Hill, for instance, broke the ACC’s color barrier in 1963. And a few years later, in March 1966, Texas Western University fielded the NCAA’s first all-black basketball lineup as it beat Kentucky in a national title game at Cole Field House.

But there have been ugly moments, too. And Saturday afternoon, when the Terps take on Syracuse, the university will pay tribute to a 76-year-old act of racism: the benching of black Syracuse football player Wilmeth Sidat-Singh in 1937.

“This posthumous tribute will not right the wrong of 76 years ago,” university President Wallace Loh said. “But it is an opportunity to learn from our history and reaffirm the commitment of our generation to racial equality and human dignity.”

STAR OF THE SHOW

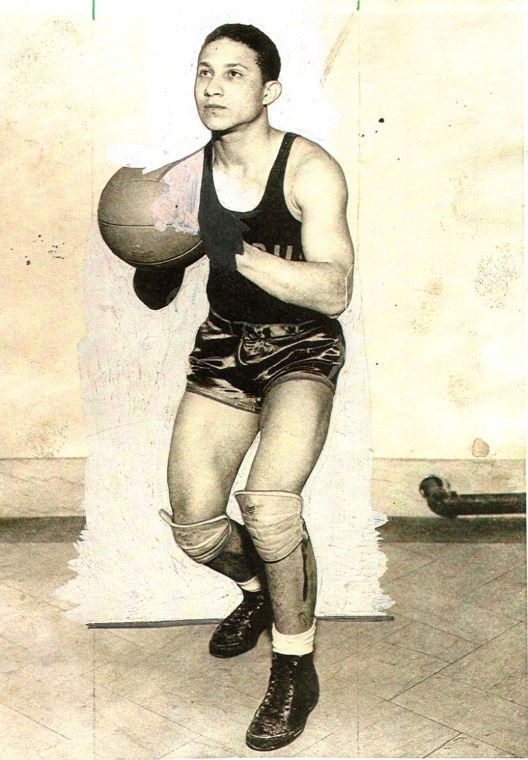

It was 1937, and Sidat-Singh was one of the brightest stars in college sports. He came to Syracuse University on a basketball scholarship, and his talent was so highly regarded that Syracuse’s basketball team would eventually retire his No. 19 uniform. He also joined the football team as a halfback, a sort of hybrid between the modern quarterback and running back — a position that required tremendous explosion and vision. Sidat-Singh had both.

Sidat-Singh 1

Under the direction of coach Ossie Solem, the Orangemen had started the 1937 football season 3-0. Sidat-Singh was gaining popularity as one of the best “Hindu” athletes in the world, and sportswriter Grantland Rice dubbed him “the Syracuse walking dream” in a poem.

Sidat-Singh and the Orangemen were set to face the Terrapins at Memorial Stadium in Baltimore on Oct. 23, 1937. The Terps were off to a 3-1 start under coach Frank Dobson, and undefeated Syracuse was coming off a critical win against Cornell. The stage was set for an important game.

Then came the newspaper report.

“THEY CALL HIM A HINDU”

Sam Lacy, a sportswriter at the traditionally black Washington Tribune newspaper, got the scoop. Lacy’s story ran just before the game under the headline, “NEGRO TO PLAY U. OF MARYLAND,” its subheading: “THEY CALL HIM A HINDU.”

The story of the remarkable football player from Syracuse was different from the one his rivals and allies spoke of — Wilmeth Sidat-Singh wasn’t “Hindu” or even of Indian descent (the moniker “Hindu” was also used to refer to race at the time). He was an American black man.

Sidat-Singh 2

He was born Wilmeth Webb in Washington in 1918. When his father died of a stroke in 1925, his mother, Pauline Miner, married an Indian doctor named Samuel Sidat-Singh. Wilmeth’s stepfather adopted him and shared his surname, transforming Webb into Sidat-Singh. And when the family moved to New York, the black kid from Washington became the Hindu from New York.

Kumea Shorter-Gooden is not only this university’s chief diversity officer but also a relative of Sidat-Singh through marriage. No one knows for sure if Wilmeth Sidat-Singh felt a connection to the Hindu faith or the Indian nationality, but Shorter-Gooden said the assumption that he was Hindu simplified Sidat-Singh’s athletic career.

“He knew that being black was less palatable than being Indian,” Shorter-Gooden said.

Sidat-Singh pullquote 1

Sidat-Singh starred for Syracuse in both basketball and football, but the school’s northern location didn’t shield him from the full force of racism. He had to live off the campus, away from the rest of his teammates and in a “bad part of town,” said Dave McKenna, a longtime Washington journalist who has penned features on Sidat-Singh for The Washington City Paper and Deadspin.

“They did not treat him well at all,” said Lyn Henley, a cousin of Sidat-Singh.

Henley never met Sidat-Singh, but he developed an interest in the athlete’s story after his father told him about their relative in the 1960s.

While other races and ethnic groups still faced discrimination, Shorter-Gooden said their plight wasn’t as entrenched in American society as that of black Americans, a population tied to generations of slavery and racial conflict. For those of Indian descent, it was more difficult to find a justification for marginalization.

“That’s very much part of the U.S.’ racial history,” she said.

In Sidat-Singh’s case, it would keep him off the Baltimore field.

SIDELINED

After learning Sidat-Singh’s background, university administrators acted swiftly to prevent him from playing in the Saturday game. The Terrapins threatened to cancel the game if the Orangemen’s black star took the field. A Hindu wouldn’t have been such a problem, officials decided, but an ordinary black man would not be allowed on the field.

Syracuse obliged, and Sidat-Singh sat. As he watched from the sideline, the Orangemen were blanked, 13-0, in the team’s first loss of the 1937 season.

Henley’s father and a group of friends and family showed up at the game expecting to see Sidat-Singh on the field, going head-to-head with the Terps. What they found was their friend and relative kneeling on the sideline, a towel over his head as a pounding rain came down on him for hours.

“What does that do to your head, to be treated that way?” McKenna said. “On paper, that’s just about as brutal as it can get — that kind of segregation.”

Dobson, then the Terrapins’ coach, first denied any involvement in Sidat-Singh’s exclusion.

“I know nothing of any reported agreement to keep Sidat-Singh out of the game,” he told The Baltimore Afro-American after the game. “I had my hands too full looking after my own team to be bothered by what the other team was doing.”

University officials initially sought to blame Syracuse for the decision to pull Sidat-Singh out of the game. The Afro-American reported that officials at this university held Solem, the Syracuse coach, responsible for the decision, but Solem denied he had made that call. There is no evidence to suggest that Syracuse pushed particularly hard to keep Sidat-Singh on the field.

“Why, the dirty so-and-so’s, [the Terrapins] know good and well that they were responsible,” Solem said to The Afro-American. “They can’t dump the matter into my lap like that!”

Geary Eppley, this university’s athletic director at the time, eventually took responsibility for the agreement that kept Sidat-Singh on the sidelines, the paper reported.

A similar exclusion occurred in this state several years earlier, when Navy’s football team forced Ohio State tackle Bill Bell to sit out a game in Baltimore in 1930 because he was black. When Navy visited Columbus the next season, Bell was a force in a dominating victory, according to The Afro-American.

The same would apply to Sidat-Singh. The next season, the Terps visited the Orangemen in Syracuse. Sidat-Singh, by then a senior, played, and Syracuse waxed the Terrapins, 53-0. For Sidat-Singh and the Orangemen, it was their most lopsided victory of the season.

THE AIRMAN

Sidat-Singh 3

After his time at Syracuse ended, Sidat-Singh spent several years playing minor-league professional basketball and football up and down the East Coast. Major-league professional football — now the NFL — wasn’t open for black players.

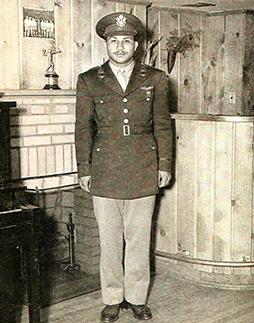

Sidat-Singh’s athletic career ended in 1942, when duty called and he enlisted in the military. Sidat-Singh joined the 332nd Fighter Group, the segregated Air Force unit that was later dubbed the Tuskegee Airmen.

The next year, Sidat-Singh was on a training flight over Lake Huron when his plane crashed into the lake.

Sidat-Singh was 25 years old when a diver found his body miles away from the base where he was training. He had tried to parachute to safety but didn’t make it.

Sidat-Singh’s end kept with a life trajectory that reads like tragic fiction: a dead parent at a young age, brutal discrimination and an untimely death.

Sidat-Singh pullquote 2

“It’s poignant. It’d be hard to write a more kind of tragic, quick ending to such a quick story,” Shorter-Gooden said. “He never had a chance to realize his full potential.”

Sidat-Singh’s life story took on a mythical quality for some.

“Will has had a hard game and he is resting — just as he always did before the second half,” prominent sportswriter Grantland Rice wrote in The Afro-American after his death. But no one would see the rest of Sidat-Singh’s game.

BLIND EYES ON A BLACK EYE

McKenna, the reporter who has been “obsessed” with this story for years, has become an authoritative expert on Sidat-Singh’s life and plight at this university. He said the story is one of the most fascinating in Washington sports history, but racial disparities from the area at the time have kept it from being widely told. McKenna himself only stumbled on it while perusing archived Washington Post editorial letters on other subjects.

“This guy’s life is unreal. He’s got a Hollywood life; he’s a superstar athlete, he dies a patriot’s death, he’s from Washington, D.C., he’s got this bizarro incident in Maryland,” McKenna said. “I’m going, ‘Why don’t we know this?’ It was because he was from [the black] half of town.”

The knowledge gap has bothered Lyn Henley, a cousin of Sidat-Singh’s who never met him but has told his story for years.

“They had the first African-American player [in the ACC] and they were kind of puffing out their chest,” he said. “But I’m thinking, ‘But you still have not acknowledged at all what happened all those years ago with my cousin.’”

Even Shorter-Gooden, a distant relative and the person in charge of promoting diversity on this campus, didn’t know about it until a year ago, when McKenna’s 2008 Washington City Paper article came to her attention.

She sent the piece to university Athletic Director Kevin Anderson, who she said told her: “We must do something.”

And so it will be. Saturday’s meeting marks Syracuse’s first game against the Terrapins in this state since 1991, and the athletic department plans to formally recognize both the player and the incident for the first time.

Shorter-Gooden said about 20 family members will watch the Terps take on the Orange from a suite in Tyser Tower. During the first quarter break, relatives will be invited onto the field, and the public address announcer will say a few words about Sidat-Singh.

Darryl Hill will also be present, calling attention to a positive part in the university’s racial relations history at the same time it recognizes a decidedly negative one. The Terrapins’ and the Orange’s current athletic directors will join him, athletic department officials said.

“After visiting with Kumea Shorter-Gooden and reading Mr. Sidat-Singh’s story, we felt compelled to recognize him for his significant accomplishments and contributions,” Anderson said in a statement provided by the athletic department. “We look forward to welcoming his family and friends to Saturday’s game against Syracuse for an on-field ceremony.”

Saturday’s ceremony, university officials and family members have said, is a step toward healing a deep, discriminatory wound.

“It’s a relief,” Henley said. “I feel like it’s a weight off of my shoulders.”

Sidat-Singh pullquote 3

Many of the campus’ current senior officials — from Loh to Provost Mary Ann Rankin to Anderson to Shorter-Gooden — only arrived here within the last few years. When she brought Sidat-Singh’s story to her colleagues, Shorter-Gooden said they were receptive and decisive — convinced something had to be done, whether previous administrations engaged it or not.

“It didn’t take much,” she said. “A lot has changed, and I’m in this role where I’m able to facilitate something that, for whatever reason, hasn’t happened before.”

When Henley and other family members take to the Byrd Stadium turf for Saturday’s ceremony, thousands of football fans will hear the same story Henley has told relatives at family reunions for years. It will be a deeply emotional moment for a man who has spent much of his adult life trying to spread word about his cousin and tears up even talking about Sidat-Singh over the phone.

“I retell his story so no one will forget. This completes the story,” he said. “I never thought — I never, ever thought — that I would live to see this happen.”

Sidat-Singh in his military uniform.

Sidat-Singh playing basketball