It started with a stroke of luck, and now a university athlete is returning to his roots to help women in Kenya.

In 2009, Kikanae Punyua, now a junior at this university, was offered an opportunity: He and one other male student in his Kenyan high school were selected to spend a year in the U.S. as part of an American Field Service exchange program. At 17 years old, Punyua left his hometown of Ntulele, a small village west of Nairobi, to spend his junior year at Wilde Lake High School in Columbia.

When his visa expired, he went back to Kenya, only to return to the U.S. when Glenelg Country School, a private school in Ellicott City, offered him a scholarship for his senior year. Punyua thrived as a distance runner and earned a track scholarship at this university.

Punyua lives almost 8,000 miles away from his biological family, but he hasn’t forgotten where he comes from. The economics major established the Osiligi Foundation in 2011 to improve the lives of women in the Maasai tribe, who often face genital mutilation and struggle for the right to an education.

“I have two younger sisters, and I really didn’t want them to go through it,” he said. “I felt I had to step up and do something.”

So he brought up the idea to his father, an elder in his Maasai clan, and asked for support. It would be hard to change the tradition, Punyua’s father told him. But his father raised money through Osiligi and bargained with the other village elders, offering to build a clinic in Ntulele if the villagers stopped the practice of genital mutilation. Punyua expects the facility to be completed in summer 2014.

It was a concrete example of his work paying off, but Punyua said he wanted a more reliable way of sustaining the clinic than just a donation-dependent charity. This summer, he founded Rafiki Beads, a business that sells beaded jewelry made by five women in Ntulele. Bracelets, necklaces, earrings and keychains are made in Kenya and sold in the U.S., with the profit going back to the women and to the foundation.

The workers have minimal skill sets, Punyua said. Even in an area modernizing as rapidly as Kenya, he said, most women are illiterate and unable to change the lives laid out for them.

They might be lacking in other areas of expertise, but the women of Ntulele are masters with beads, Punyua said. Rafiki Beads runs under the motto that “beauty empowers,” and Punyua considers his products “socially conscious jewelry.” Accessories are intricately designed, and beads ranging across the color spectrum tend to be no larger than pen tips. Other items, such as the company’s Mzuri earrings, are made from patterned wood.

“It’s very important for women to have a voice in society, too,” Punyua said. “I feel like if you empower women, you empower a whole society. That’s what we’re trying to do.”

Alex Willett, Punyua’s business partner and roommate, handles the technical aspects of the business. A junior economics major with an interest in graphic design, Willett handles Rafiki Beads’ website’s layout and daily operations. He works to create an image for the company and further brand awareness.

Willett contacted Punyua about launching the website when he realized if he really wanted the world to be a better place, he would have to take action. He pointed to a scene in Hotel Rwanda in which a journalist tells the main character that people in the West would see video footage of brutality in Rwanda, call it awful and then go back to eating dinner.

“That really struck a chord in me, and I felt that I really had to do something,” Willett said. “I can’t just promote world peace — I can’t promote helping out others — without actually doing something myself.”

Punyua and Willett said they sold about 130 pieces of jewelry in their first month, with prices ranging from $5 for keychains to $20 for necklaces. Moving forward, they plan to design a signature bracelet that could appeal to men and women. When Punyua returns to Kenya this winter, he said he wants to photograph the women who design the jewelry and put them on the website so customers can know who made the pieces.

“We’re not only selling our product, but we’re selling a story,” Punyua said. “You’re not only buying a product, but you’re changing someone else’s life.”

Punyua’s establishment of a social enterprise comes as no surprise to Whitty Bass, Punyua’s track coach at Wilde Lake. Bass and his family have hosted Punyua since 2009, and Bass said he’s witnessed Punyua’s deep family roots and determination to make a difference.

On Punyua’s first day with the Wilde Lake cross country team, Bass instructed him to run with the freshmen. He had never seriously played a sport before, and Bass wanted to ease him into the physical stress of distance running. After 35 minutes, the younger athletes started trickling back from the run, but Punyua was nowhere to be found.

“What do you mean you haven’t seen him?” Bass asked.

Punyua had run eight miles stride-for-stride with the varsity team, in sneakers Bass described as “blue canvas boat shoes with hardly any sole.” For the next two weeks, Bass made him take ice baths to bring down the swelling. But by the end of the season, he was the top runner on the team.

Punyua’s competitive nature as a runner is not the only quality that will contribute to Rafiki Beads’ success, Bass said. Punyua is deeply considerate and warmhearted, he said, perhaps a result of his upbringing as one of 11 children in a grass hut without electricity or running water.

“He’s an extraordinary man,” Bass said. “Everybody instantly takes to his gentleness, his kindness. We just found him a joy to be with.”

When Punyua was young, few Ntulele girls went to school. Some were married off in their teens and had children before the age of 20. Most of these women could not read. But things are changing in Ntulele, and in Kenya in general, Punyua said. Most girls in the village attend school, he said — a trend toward an increasingly educated population throughout the country.

After graduation, Punyua plans to run his business full time. At 21 years old, he’s focused on growing his company to a nationally recognized level with the hope of bringing about equality for women living thousands of miles away.

“We’re all here for a purpose, and I feel my purpose is to help as many people as I can,” Punyua said. “Rafiki Beads is not just a product, it’s part of who I am.”

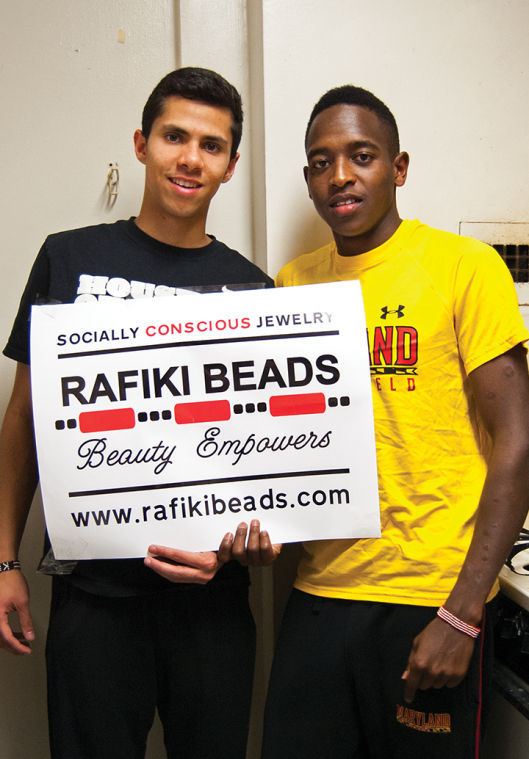

Kikanae Punyua and Alex Willett started the Rafiki Beads business to build a clinic in Kikanae’s home village in Kenya and help women there get an education.

Kikanae Punyua and Alex Willett started the Rafiki Beads business to build a clinic in Kikanae’s home village in Kenya and help women there get an education.