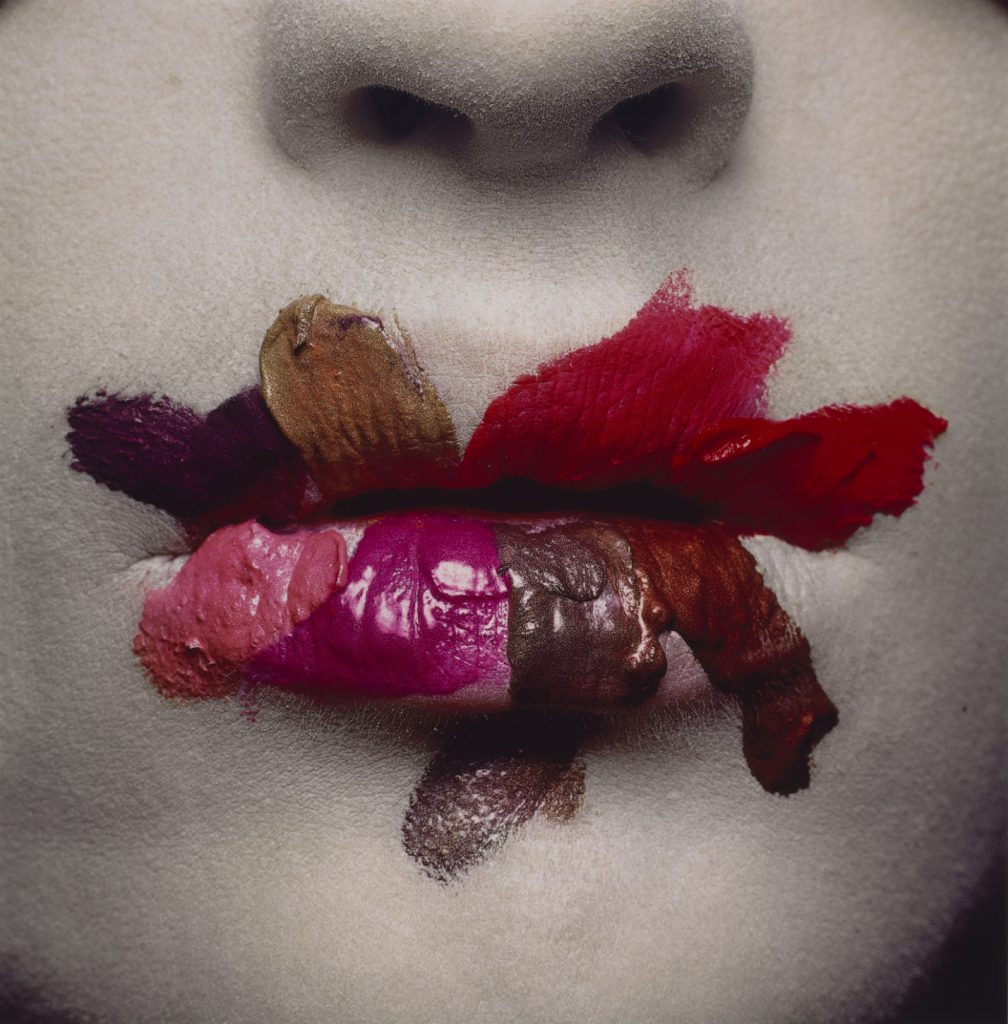

Irving Penn lipstick

At a press preview Thursday, Smithsonian American Art Museum Director Elizabeth Broun recalled an odd gift exchange with legendary fashion photographer Irving Penn, the subject of a marquee show that opened Friday at the museum.

“One time I gave him a book by Vladimir Nabokov that was a favorite,” Broun said. “And he said, ‘Oh yeah, I photographed him. I never really read his books. You know, I photograph all these literary figures; I never read their stuff.’”

“He said, ‘I want to just encounter them as people and do the photograph without bringing the book experience to it.’”

And encounter them he did. The Nabokov portrait in the catalog, which Penn sent Broun as a gift following their conversation, shows the famed writer not among the trifles of his craft (pens, pencils and other ephemera), but running semi-focused through a field of butterflies, a nod to Nabokov’s other calling: lepidoptery.

This exchange, exemplary of Penn’s fantastic career in art and photography — which spanned decades at Vogue and encounters with dozens of influential culture movers and shakers — typifies how Broun and exhibition curator Merry Foresta described the irreverent “Mr. Penn.”

“He believed strongly in his own vision,” Broun said. “He knew what he thought.”

And he knew what he wanted to capture.

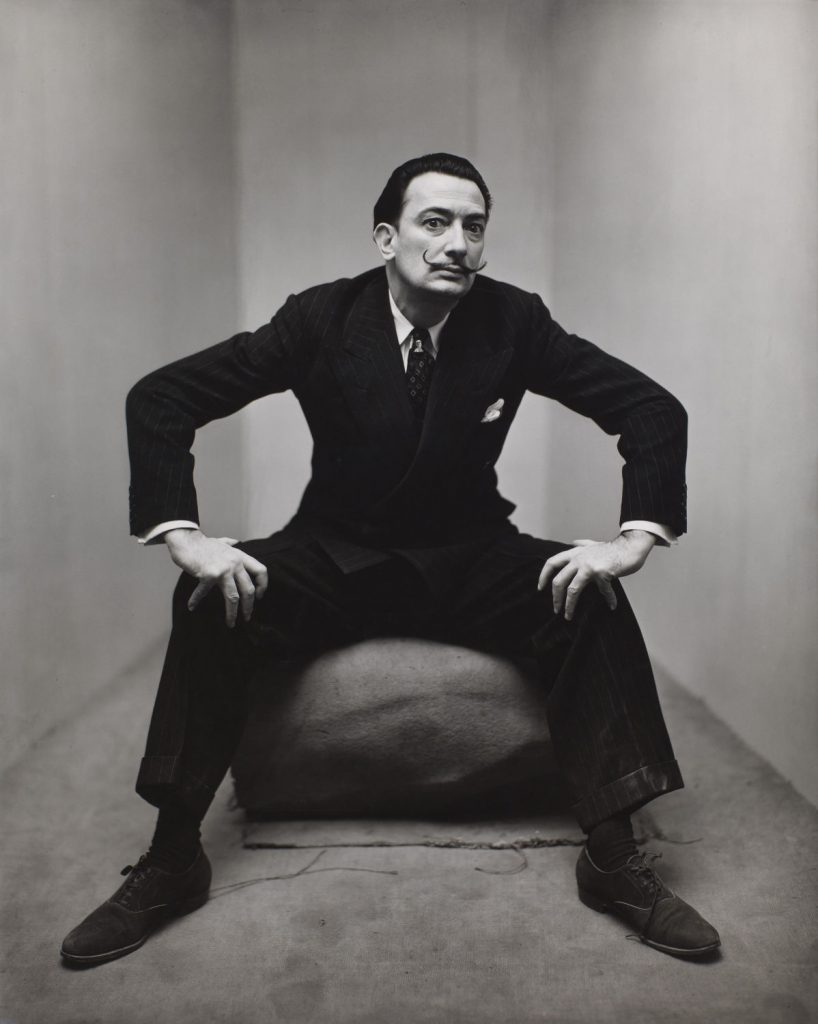

Irving Penn Dali

From his iconic portrait of Spanish surrealist Salvador Dalí to his early image of a young black boy in the 1940s South, from the adoring pictures of his gorgeous wife (Lisa Fonssagrives, often called “the first supermodel”) to his photo of a pensive Langston Hughes, Penn was a consummate aesthete.

His unequaled eye for beauty and art came from early encounters with beauty and the beautiful, an area of Penn’s life explored in depth for the first time by this must-see exhibition.

“These were images that no one had seen very many of,” Foresta said. “These were images … that held the seeds to understanding the Penn we all thought that we knew.”

“They tell a story of a young man who went to art and technical school,” she continued. “And who he encountered there was a teacher named Alexey Brodovitch. … And not only was he a teacher, but he also happened to be the art director for Harper’s Bazaar.”

Penn became an assistant to the master designer and photographer.

“And at Harper’s Bazaar in the late 1930s, there is almost a revolution in publishing going on,” Foresta said. “[Brodovitch] redesigned the pages, he made images look better than they’d ever looked before. He brought in new writers to add literature to the pages, and more importantly, he introduced a whole portfolio of European refugee artists” — Dalí and Joan Miró among them.

“And who was on hand to greet these artists?” Foresta asked. “Young Irving Penn. And who was there to open the envelopes that were full of their drawings? Young Irving Penn.”

“This is really Penn’s education,” Foresta said. “He begins his art education in the offices of Harper’s Bazaar.”

These early experiences heavily informed the art-historical lens with which Penn approached subjects throughout his illustrious career. It informed more than how he saw his subjects — whether a cut of beef captured in impossible perfection or the great writer Truman Capote at two points in his life, decades apart. It informed how Penn saw himself.

Because Penn was not, at least to himself, a photographer.

“In his mind, he was first and foremost an artist,” Broun said. “He’s often credited with sort of making photography a fine art. And he did do that, but that’s because, in his mind, it wasn’t like they were two different things.”

“He was an artist,” she said. “And he thought like an artist. And … it was in his soul to be thought of as an artist.”

As an artist, he wanted to be among the scene.

“Something amazing happens,” Foresta recounted. “Here he is, he’s assistant to Alexey Brodovitch at Harper’s Bazaar. He’s in New York; he’s in the mix.

“What does he do? … He announces that he’s leaving his job and he’s going to Mexico to paint. Pretty ballsy activity for a young man with a good job at the end of the depression.”

In Mexico City, in his travels through the American South, in his voyage to Europe at the close of World War II, he creates stunning images of humanity — images that force a welcome reevaluation of the Penn “we all thought we knew.”

“When we consider all of his different work, there is a real sense of art being woven,” Foresta said. “A consciousness of art and its antecedents and what it means to be an artist.”

This consciousness is enhanced by his early work, but confirmed and elevated by the acknowledged Penn.

“It’s certainly true through much of the work he did as a still-life photographer … that he did as a portraitist; that he did as a fashion photographer,” Foresta said.

Irving Penn fruit

There’s the cheeky stack of cubed frozen foods, striking in its color and form but made lively by its playful subject matter. There’s the signature image of a bumblebee on Marilyn Monroe-esque lips, as off-putting as it is beautiful.

His work brushing L’Oreal cosmetics perfectly yet haphazardly onto models’ faces is luxuriant and profane, as jarring as it is entrancing.

The works, Foresta said, showcase “beauty in the extreme.”

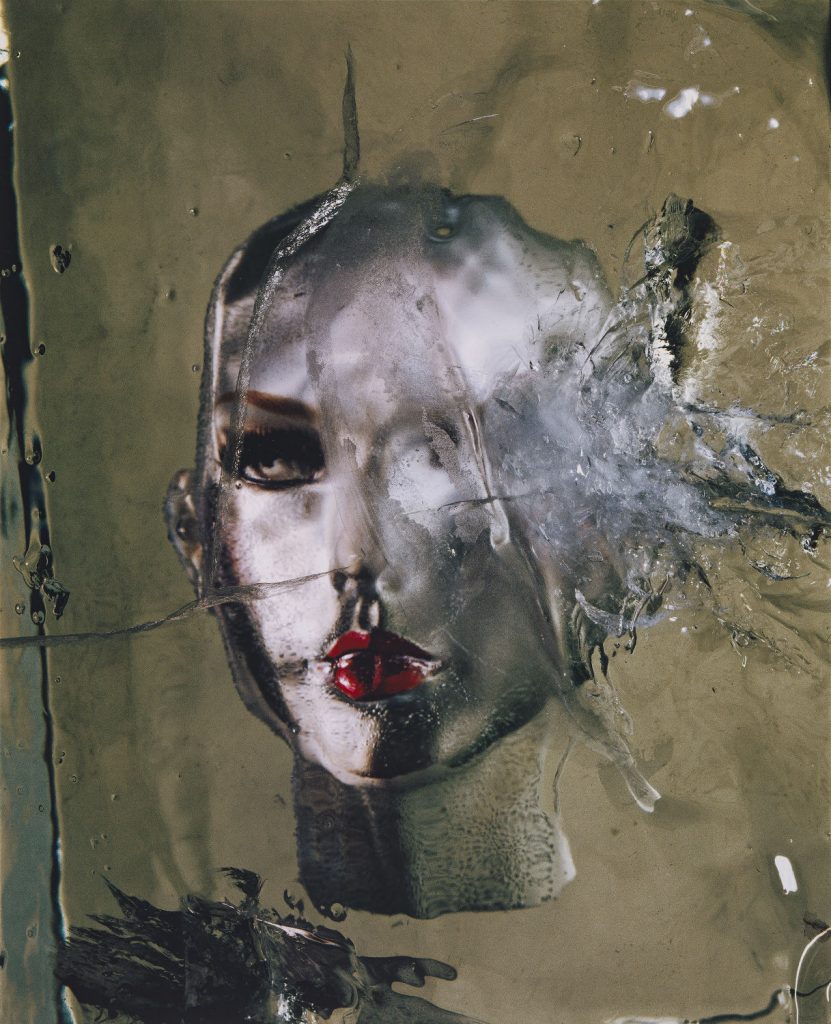

Irving Penn model

“We have a … photograph made probably for an article at Vogue about how ice water will tighten the skin and cool your face before you put makeup on,” Foresta said, referencing the verdant, arresting image that begins the 146-work show.

“And how does Penn photograph it? He takes a plaster mannequin, has it made up exquisitely, and he freezes it into a block of ice and hits it with a hammer,” Foresta said. “And that’s the photograph we have: striking, powerful images, at a time when magazines were needing to rely on striking, powerful images to attract their readership.

“We have that idea of Penn that begins early and stays throughout,” Foresta said.

The Penn on view is the Penn you knew (or at least should’ve known). But it is expanded, built upon and explored in a way only such a grand monograph show as this can. As the title suggests, the show goes “beyond” in many satisfying ways, all the while maintaining a solid grounding in the man himself.

“We want you to see the full Penn,” Broun said. “He was more interesting, more complicated, more curious, more experimental, more surrealist — and he had so many arrows in his quiver.

“This whole thing is pretty dynamite. And we want you to see it all.”

“Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty” runs through March 20 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which is nearest to the Gallery Place/Chinatown Metro station.

CORRECTION: Due to an editing error, a previous version of this story incorrectly attributed Elizabeth Broun’s quote “We want you to see the full Penn” to Merry Foresta. The story has been updated to reflect this correction.

Penn’s 1986 work brushing L’Oreal cosmetics perfectly yet haphazardly onto a model’s face is luxuriant and profane: as jarring as it is entrancing.

Penn’s 1947 portrait puts surrealist artist Salvador Dalí in a corner, a common Penn trope.

Penn’s cheeky stack of cubed frozen foods in this 1984 print of a 1977 work is striking for its color and form but made lively by its playful subject matter.

In the show’s introductory work, Penn illustrates a story about ice water’s benefits to skin by freezing a made-up mannequin in ice and hitting it with a hammer.