The story of WMUC is one of resistance, resilience and revolution.

World War II, Vietnam and Apollo 1; Louis Armstrong, Fats Domino and The Beatles — a microcosm of modern American history. And the university’s student-run radio station has been around to see it all.

In honor of the station’s 65th year under its present call letters, university archivists are assembling an exhibit on the station’s history. The exhibit, titled “Saving College Radio: WMUC Past, Present and Future,” will open in September in Hornbake Library’s Maryland Room and run through July 2014.

For project leader Laura Schnitker, it’s a look into the past of the college radio station she’s come to love, both as an ethnomusicologist and as a station volunteer for the past eight years.

“I like the spirit of college radio. I like to hear stories about especially undergrad students who come to the university and maybe feel like they don’t quite fit in for whatever reason,” she said. “And they find WMUC is a very supportive community, and they feel comfortable there and are able to find their own voice.”

To the students who have come and gone over WMUC’s airwaves, the station means everything. It’s not only been a second home but launched the careers of the likes of news anchor Connie Chung, sports journalist Bonnie Bernstein and conservative pundit Mark Davis.

“There are a lot of people who really benefited from the radio station and will continue to support it for the rest of their lives,” said Steve Rudenstein, who worked for WMUC Sports between 2001 and 2005.

But for all the station has done for the students who embraced it, its existence is in jeopardy. The past decade has not been kind to WMUC, between funding crises and the controversial expansion of a larger Baltimore station in 2006 that threatened to take over WMUC’s 88.1 FM signal.

The exhibit, Schnitker said, aims to fulfill two goals. First, to pay tribute to the station’s legacy in music, sports and news. And second, to draw attention to the station as something worth saving for future students.

In a dusty room in Hornbake Library, manila folders are laid out on a table. Schnitker has filled them with photos, fliers and newspaper clippings she’s been collecting with the help of her student assistants over the past seven months.

There are homemade fliers from the ’90s and yearbooks from the ’50s. There’s a T-shirt and a promotional Frisbee — even a press pass from the ’70s. And that’s not including the station’s collection of 1,500 audio reels that Schnitker and an assistant spent months digitizing.

One station alumnus scoured auction websites so he could purchase and donate the exact model of the recorder he would have used in the ’70s.

Every new piece discovered or donated by an alumnus fills a hole in the broader picture of a station’s rich, eclectic and scattered history.

“It’s a hidden gem on campus,” said alumnus CJ Holley, who worked for WMUC Sports until 2005.

The station sits on the third floor of the South Campus Dining Hall, across from The Diamondback’s newsroom, full of couches bleeding stuffing and piles of old equipment in comfortable chaos. Paint on the walls is peeling, and corners are dusty.

“The place looks almost identical to the way it did back in the ’80s,” said Arthur Harrison, another alumnus who has spent time at the station intermittently since the ’70s.

But its battered appearance is part of its appeal. It’s clear that WMUC is one of the oldest college radio stations in the country and one of the few to boast a free-form format — DJs can broadcast as they wish.

It all began in 1937, when CBS donated radio equipment in an attempt to turn the university into a talent pool. That donation paved the way for students to set up The Old Line Network, the first incarnation of a student radio station, in 1943. But campus radio had a rocky start fraught with financial and logistical troubles.

The Old Line Network, which broadcast daily, was short-lived. The student staff traded their broadcasting equipment for guns and military uniforms and shipped out to fight in World War II. With no one to run the station, it disbanded.

Students worked to raise more than $1,000 to re-establish the campus radio station during the 1947-48 school year. They took on the letters WMUC in 1948 when the FCC gave students’ first choice of call letters, WUOM, to the University of Michigan.

WMUC’s first foray in radio didn’t last long, either — it shut down after only three days of broadcast because of poor transmission, and students weren’t able to revive it until 1949.

The station moved many times over the years, occupying buildings that have since been demolished. At one point, in about 1951, DJs were broadcasting out of a basement bathroom in Calvert Hall, which was an all-male residence hall at the time, and female students had to find ways to slip into the building undetected.

WMUC didn’t take up residence in its current location, tucked away above the South Campus Dining Hall, until 1974.

“What surprised me was how many different characters the station has embodied over the years, depending on the types of students who worked there,” Schnitker said.

Broadcasting six days a week, the students of the ’50s placed a heavy emphasis on live broadcasts, from sporting events to concerts. And in the ’60s, students who ran the station were set on professional careers. Broadcasts were held to high standards and students sold ad space to local businesses to bring in revenue.

They also recorded several high-profile interviews, including with astronaut Gus Grissom, who died in the Apollo 1 tragedy in 1967; Chubby Checker; Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons; Fats Domino; and Bill Cosby. Station DJs also set the world record for collegiate disc jockeying in 1975 after staying on air for 101 hours.

Schnitker said a station alumnus recently sent her an audio recording of a 1964 interview with The Beatles after its show at the Washington Coliseum, the band’s first show in the United States. Four station DJs convinced John Lennon to read several WMUC promotional spots, which played for years afterwards. Those promos were some of the last The Beatles ever did; the band’s manager asked them to stop reading promos shortly after.

WMUC was always a progressive and unique place, alumni said, but in the ’70s, it began to embrace a more diverse crowd. Anne Edwards, a noted figure in TV journalism and 1972 graduate, became the first female station manager in 1971, and “Yesternow,” the first program geared toward black students, premiered in 1972.

That decade was also when Davis, a conservative radio talk show host and columnist in Texas, got his start. Between 1975 and 1979, Davis was a reporter for WMUC News, where he was a firsthand witness to the 1978 state governor election, in which Harry Hughes unexpectedly defeated Blair Lee in the Democratic primary.

“I was halfway through my journalism degree, thinking for all the world that my career would be print-related,” Davis said. “There was one thing that happened that was a big part of the state’s history, and I got to see it firsthand, and it made the journalism bug bite in me the way it never had before covering things in print.”

Davis also remembers how difficult it was for the station to obtain an FM license. For five years, the station bid for a license, and the FCC rejected it twice before granting the students a license to broadcast on 88.1 FM.

The ’80s ushered in a different era. With an FM license also came a group of students with a fresh outlook, one The Washington Post at the time said gave “listeners and disc jockeys a chance to revel in the thoroughly bizarre.”

“They were interested in music that wasn’t being played on other commercial stations, nothing in the Top 40,” Schnitker said. “These were students that, sort of because of their eccentric musical tastes, thought they were outsiders to the mainstream.”

Harrison, a student in the ’70s, returned to the station frequently in the ’80s as an electronic musician. He would make his way to the third-floor station and sit with friends and acquaintances, playing an eerie-sounding electronic instrument called the theremin and listening to live performances in the station’s main room.

“Along with the chaos of the station comes an inherent freedom,” he said. “Radio was one of the few mediums by which you could reach the public.”

Into the ’90s, WMUC continued to play fringe artists, including a live performance from then-up-and-coming singer-songwriter Elliott Smith , who remains a cult icon.

There is some dispute about whether the Smith session took place in 1996 or 1997, but student-DJs made national headlines in 2011 when they unearthed the missing recording — eight years after Smith’s death — and a never-before-broadcast song. The ’90s also saw the launch of Third Rail Radio, the live-act show that’s been broadcasting since 1997.

Josh Madden, assistant director of undergraduate programs in the journalism college, said he has fond memories of working at the station with Holley, now an ESPN.com editor, and Rudenstein, now director of major gifts and athletic fundraising at Rider University, in the early 2000s. Madden broadcast for WMUC Sports between 2002 and 2005, when WMUC Sports was beginning to stream online.

“There was always a rush when you’re at a game,” Madden said. “Myself as well as my peers always had the mentality that we would be watching the game anyway, so broadcasting the game and giving our own opinions and thoughts and analysis was something we all really treasured.”

WMUC had agreements with several university sports teams, and student journalists traveled with the teams to games across the country.

“We went on some great trips,” said Rudenstein, who added WMUC influenced his decision to enroll at the university. “I remember going to Jacksonville [Fla.] to the Gator Bowl my junior year, and my senior year, Maryland was in the NIT final four, and we went up to Madison Square Garden.”

The AM stream died out in 1999, but it was soon replaced with what alumni said was the biggest change to the station since it received an FM license: WMUC Digital, an online station, premiered in 2008.

Keeping it alive hasn’t been easy.

“I’ve seen the station go through cycles of being almost in a state of neglect and coming back to life by students who come in and see it as something worth investing their time in,” Schnitker said.

One of the worst crises was a serious funding withdrawal two years ago. The station’s Student Government Association funding was cut in half, so WMUC was looking at shutting down, Schnitker said.

Senior international business major and former business manager Phil Mulliken described a power struggle and a tense atmosphere between old and new staff that also threatened the station.

“The old station staff and the new station staff were fragmented; they didn’t really trust each other very much,” Mulliken said. “Nobody really had perspective of the station as a whole.”

With a concerted effort, WMUC regained its footing. There were donations and events to get the station exposure, including an agreement with the Washington Nationals in which a portion of the ticket proceeds went to the station. Even Rivers Cuomo, the lead singer of alt rock band Weezer, tweeted his support for the station.

“It’s been a couple years, and we’re still struggling,” said station manager Lealin Queen, a senior English major. “Money’s always an issue. It’s almost expected that we’re going to come into some hard times.”

But WMUC has always persevered. Even when the station is strapped for cash, the community behind it refuses to let it die.

“We’re one of the only free-form college stations left … continuing that tradition is just a really big thing for us,” Mulliken said. “There’s a lot of history here, and I think it needs to be preserved.”

Station supporters are confident the debut of the new exhibit will signal a new chapter for WMUC and college radio. With the old recordings and vintage scripts comes a new hope that WMUC will indeed be able to continue writing its history for much more than 70 years.

“So far, the Nazis are the only thing that has kept WMUC from broadcasting,” Queen said.

Schnitker said that in addition to the exhibit, archivists hope to hold a benefit concert and symposium on college radio. The station also has plans to host a concert with other local college radio stations and spread the WMUC name.

“Even though it’s very different, and everyone is of a very different generation, the job is exactly the same: to provide a place for people who are 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 to come in and have the bug bite,” Davis said. “To actually do it so you can close your eyes and imagine yourself doing it for money, doing it for a living.”

Students Pat Callahan and Herb Brubaker work on a WMUC broadcast in 1955.

A student DJ at work at WMUC in 2003.

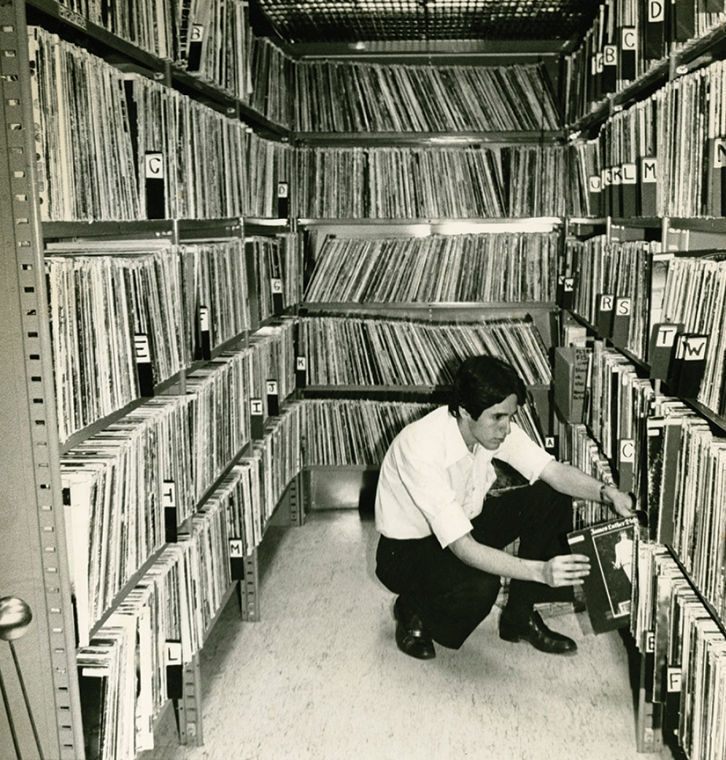

A student browses WMUC’s record library in 1979.