University professor Thomas C. Schelling was sound asleep early yesterday morning when his phone rang.

By the time he hung up from the call, Schelling, 84, knew that a lifetime of work had paid off in one of the biggest ways possible. He had become the third faculty member in university history to be awarded a Nobel Prize.

Just hours later, the economics and public policy professor emeritus stood at a campus news conference where his 2005 Nobel Prize in Economics was officially announced.

“If I’m looking too pleased, I can’t help it,” Schelling said to a crowd of colleagues, university administrators, family and press gathered on the campus yesterday.

The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded the prize to Schelling for his work with game theory, a method to analyze human behavior that predicts the reactions of individuals, corporations or nations based on the actions of others in competitive situations.

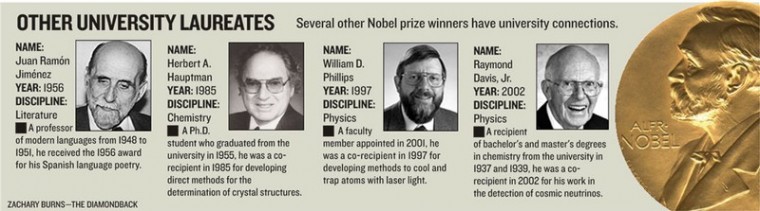

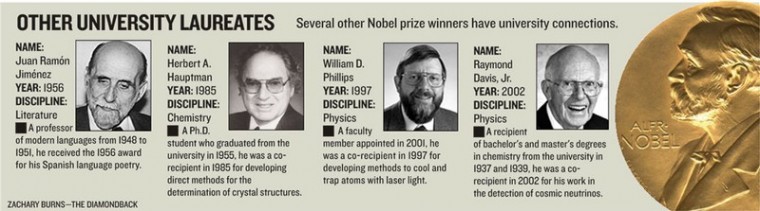

University officials said Nobel prizes, also given to Professors William Phillips for Physics in 1997 and Juan Ramon Jimenez for Literature in 1956, help the university attract top-notch faculty and bolster the university’s reputation.

“People want to be where they can surround themselves with colleagues of comparable ability,” Provost Bill Destler said. “This recognition attracts both great faculty and great students.”

Schelling’s work, along with that of co-prize winner Robert J. Aumann of Hebrew University in Jerusalem, helped to establish the dominant approach to understanding international cooperation and conflict concerning nuclear proliferation and arms control. His most famous book, The Strategy of Conflict, applied game theory to the threat of nuclear war.

Schelling will receive the award at ceremonies in Stockholm, Sweden, in December. He and Aumann will share the award of approximately $1.3 million, but Schelling said “it’s too early to have any budget plans.”

During a standing ovation at the news conference in the Samuel Riggs IV Alumni Center, Schelling shared a smile with his wife, Alice, before humbly motioning for the audience to be seated.

Commenting on his career and fielding questions from reporters representing an array of media outlets, Schelling said he and Aumann have never worked with each other but are friends.

“It’s a honor to be associated with him,” Schelling said of Aumann. “He’s a ‘real’ game theorist, which I am not. I’m what I would call a ‘consumer of game theory.’ I can use it. It helps me think.”

Schelling, who has been at the university for 15 years, has expertise in foreign affairs, national security, and nuclear strategy and arms control.

The economics prize is not one of the original five awards devised in 1895 as part of Alfred Nobel’s will, but was established in 1968 by the Bank of Sweden to honor the Swedish inventor.

Schelling worked at Yale and Harvard universities before joining the faculty at this university in 1990. He said he was offered “a larger salary and smaller teaching load,” and that the university’s proximity to Washington and the small and personal public policy school made it more appealing.

“In terms of working with stimulating colleagues,” Schelling said, “I’ve enjoyed Maryland as much as I did Harvard.”

While teaching at this university, Schelling worked with undergraduates in the Honors Program. He no longer teaches, but is currently researching nuclear weapons and global warming and climate issues.

“One of the nicest things about tenure at the university is that you can work on whatever you want,” he said.

Schelling’s work has reached far beyond his research at universities. One of the professor’s articles provided inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s seminal Cold War-era film Dr. Strangelove.

“Kubrick spent a long afternoon in my office … and then a long evening at my house,” Schelling said in a memo to students and faculty of the School of Public Policy before a September campus screening of the 1964 movie.

“During that Cold War period, he was definitely one of the leading thinkers on nuclear war,” said Tim Gulden, a postdoctorate research fellow who works closely with Schelling in the School of Public Policy, where Schelling taught a class as recently as this past spring.

When he is not busy dealing with the logic of nuclear war and opening new fields of economic research, Schelling takes time to work out frequently at the Campus Recreation Center, Gulden said.

Schelling is also a family man. He is married to Alice Coleman Schelling and has four sons: Andrew, Thomas, Daniel and Robert.

Gulden, whose office is a few doors down from Schelling’s in Van Munching Hall, has built his research career around the ideas and fields Schelling was instrumental in creating and expanding.

“Although his personal manner is informal, one is inclined to call him Dr. Schelling,” Gulden said. “I’ve tried to call him Tom, but I can’t do it. But he’s not intimidating. He’s really extremely gracious and eloquent.”

He said the chance to work with Schelling was one of the main reasons he came to the university.

“Tom’s an incredibly thoughtful, almost shy, deliberate person,” College of Behavioral and Social Sciences Dean Edward Montgomery said. “He doesn’t say much in meetings, but when he does, it’s dead to the point. This brings with it – particularly when you think as well as he does – great power.”

Montgomery said Schelling’s most important contribution to economic and public policy is his style of thinking and teaching.

“Tom has an ability to make us think about what could be deemed intractable, difficult, complex problems in a simple, but logical way. Whether it’s things like strategic arms control, global warming, or even how you communicate with your kids, he asks: What’s the common thread?” he said. “I think he deserved the award five years ago.”

Contact reporters Kevin Rector and Connor Sheets at newsdesk@dbk.umd.edu.

University of Maryland economist Thomas Schelling has won the 2005 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics for his work in game theory analysis.