Nationwide, more college admissions officers than ever are checking applicants’ Facebook pages and reviewing their backgrounds, but officials at this university said they don’t have the time to do so, except in extreme circumstances.

Kaplan Test Prep recently surveyed 381 admissions officers from across the country and found that 29 percent of officers had Googled an applicant, and 31 percent had looked up their Facebook or other social media pages. Of those officers, 30 percent said they had found something that hurt an applicant’s chance of admission.

But at this university — which received 26,247 applications in 2012-13 — admissions officers said they are so caught up in going through applications that they don’t have time they don’t have time to do extensive background checks on each student, said Shannon Gundy, undergraduate admissions director. An initial read of an application takes about seven minutes, she said.

Reviewing Internet profiles isn’t prohibited, Gundy said, but officers won’t research a student unless they feel application information looks falsified or misleading.

“The reality is those things just don’t happen very much,” Gundy said. “We’re not sleuthing; we’re not trying to find dirt on students applying for admission.”

When officials review applications, they consider students’ grades, standardized test scores, letters of recommendation, short answer questions and essays. Sometimes, it’s easy to accept or deny students after a first read, Gundy said.

But some “on the fence” applications will go to an admissions committee of seven to 12 officers for further review, Gundy said. Sometimes, they’ll fact-check students who list unusual awards or those whose grades and extracurricular activities don’t seem to match the awards they said they’ve received. The committee might also look into students who said they spend an extensive amount of time using social media.

“Let’s say a student says to me, ‘I’ve created a website,’” Gundy said. “I see on the front page of their website they’re drinking; they’re using drugs — then yes, that’s going to affect a student’s admission decision.”

Decisions aren’t always limited to what students send to the university, either. An officer might call high school counselors or the students themselves for more information, Gundy said, or outside sources might contact the admissions office with concerns about a particular applicant.

That doesn’t mean the information necessarily will have an effect, Gundy said. For instance, Gundy remembers getting an email from someone concerned about a negative news story about an applicant. But the office had already investigated the incident and decided to offer the student admission, Gundy said.

The most common instance in which admissions officials will conduct additional research is if a student notes that he or she has received some sort of disciplinary infraction. The number of disciplinary infraction notes has more than doubled in recent years — 373 in the 2012-13 admissions cycle, up from 168 in 2009-10.

If a student’s application information is up to university admissions standards but he or she marked “yes” for a violation, officers will send the application to the Office of Student Conduct. There, James Bond, student conduct associate director, and a graduate student assistant will review the violation and clear or reject a student.

“If we can find that information ourselves, then we will,” he said. “Sometimes what we’ll do is, if students are being coy or not completely forthcoming, we’ll do a Google search and see what there is to see.”

Research often involves checking court case records, reading news articles or contacting students individually for more information, Bond said. Facebook and other social media sites usually don’t factor into the review, Bond said, because they don’t always provide accurate information.

“It’s not like we wouldn’t use Facebook, but if I see something on Facebook … We need to ask them directly what happened here; give me your explanation,” Bond said.

Most disciplinary cases, such as minor traffic or alcohol violations, are cleared, Bond said. One applicant was denied in the 2011-12 admissions cycle out of the 324 reviewed and four were denied out of last year’s 373.

Bond said the student conduct office is most concerned with students who lie on their applications. Officials might deny otherwise “perfect” applicants, or they might suspend or expel enrolled students if the office later learns about violations through news reports or by word of mouth.

“[If] we see it wasn’t just an alcohol thing but it was drugs and you attacked the police … we would look into that and say, ‘You lied on your application here,’” he said. “Had they not lied, they would still be in consideration.”

In one incident, Gundy said, university officers learned a student had taken the SAT for another student. Both students had been admitted, but because of that, the admissions office rescinded their offers, she said. The office learned of the incident just a few days before their fall move-in day, which she said was “heartbreaking.”

Not all incidents are reported or discovered. A senior history and journalism major, who asked to remain anonymous because he talked about a disciplinary infraction, said he was caught bringing alcohol to a high school football game and served a five-day suspension. But he didn’t check “yes” on his application to this university because his high school principal said the school didn’t release such information.

Though his suspension remained private, the student said he thought admissions officers had a right to use publicly available information on social media sites to review students’ backgrounds.

“The only thing that’s unacceptable is if they ask you for your private Facebook or Twitter,” he said. “If it’s public and they see something they don’t like … it could be a concern.”

Over the next few months, the admissions office plans to hire a new marketing staff and develop social networking pages to interact with applicants, Gundy said. The office will post information about events and answer questions, but Gundy said it doesn’t want to “intrude” on applicants’ personal lives.

“We recognize that in many cases, this is their means of communicating with their friends and family,” Gundy said. “We want to make sure they’re comfortable with inviting us to come with them in that manner.”

Regardless of how information is used, Gundy recommended students be wary about what they post online.

“Once it’s out, you can delete it, but if someone’s already captured it, it’s still out there,” Gundy said. “Don’t make negative decisions that you can’t fix later on. First of all, don’t do it, but if you’ve done it, don’t publicize it — that’s ridiculous.”

A Maryland Images tour guide shows prospective students around the campus. When considering students for admission, university officials said they look at many factors, but they do not usually have time to monitor students’ online presence.

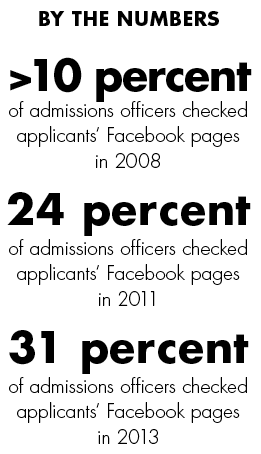

Nationwide, more college admissions officers than ever before said they have used Facebook to review applicants’ backgrounds.