Testudo the Terrapin has taken on many forms over the years: Bronzed on his proud perch in front of McKeldin Library, rallying crowds at Byrd Stadium and emblazoned on the shirts of many a Maryland fan.

But a slew of artists, sponsors and university staff are bringing a new form of the beloved mascot – 50 4-foot-5-inch fiberglass forms of a muscled, hands-on-hips grinning Testudo, planned to storm the campus and state in the spring.

The Fear the Turtle Sculpture Project, in the works for the past year under the direction of the University Marketing and Communications office, is set to become the university’s first-ever public art project, in commemoration of the university’s 150th anniversary. Staff at the office have commissioned a local artist to sculpt the Testudos, which will eventually be placed into the hands of fifty local artists who will decorate the sculptures over the winter, said Terry Flannery, assistant vice president for university marketing and communications.

As the snow melts in March, the Testudos will be brought back to the campus completely individualized. The sculptures, which were designed by Steven Weitzman of Weitzman Studios in nearby Brentwood, will be unveiled at Maryland Day April 29 and will be placed on the campus and across the state.

Artists are now submitting designs detailing how they would like their Testudo to look, and Flannery said great license has been given to artists for their ideas, including additions to the sculpture.

“Artists are invited to attach anything to it that reinforces the creative design,” Flannery said. “It’s really open to interpretation and creativity so I can’t wait to see what people come up with.”

The 50 winning designs are to be selected by committee, which includes College of Arts and Humanities Dean James F. Harris and university President Dan Mote’s wife, Patsy. Artists are free to submit design proposals framing Testudo any way they like, as long as they are family-friendly, but committee and staff members hope the designs will help celebrate the anniversary or the campus in some way, Flannery said.

Flannery said the university hopes a number of students will be participating in project designs, and her staff has reached out to a number of student groups and organizations.

“We are really excited that this gives people an opportunity to celebrate their Terrapin pride in an artistic way,” Flannery said. “Students are a really important part of that. I can’t wait to see what kinds of designs they put forward.”

The university is currently searching for sponsors for the project, with 20 identified so far. A sponsorship costs $4,000, which Flannery said covers $3,000 in production costs, plus a $1,000 compensation paid to the artist to cover time and material expenses. Flannery said artists will be matched with sponsors and the two parties can choose to work together on selecting the direction of the design.

Sponsors may also donate a premium of $7,500 in order to secure a purchase of the sculpture. Pieces not sponsored for the premium will be auctioned in September.

“Any money that we raise past the initial cost will go to scholarships,” Flannery said. Although organizers are first trying to ensure the project pay for itself, she said.

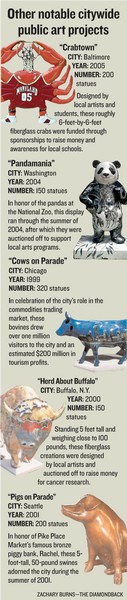

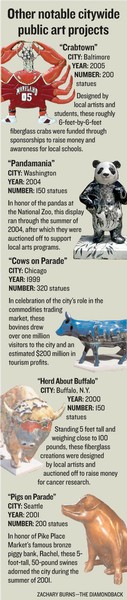

The sculptures come on the heels of other major public art projects in nearby Washington and Baltimore – giant fiberglass pandas and crabs, respectively, have sprung up in those cities the past two summers – that have been successfully used to raise thousands of dollars for various causes. One of the first American cities to fund a similar public art project was Chicago, which giant cows invaded in 1999.

Eric Friedman, who handled logistics for the crab sculpture project in Baltimore, the city’s second, said the sculptures “created a more vibrant street life,” and many people made it a mission to photograph themselves with all of the nearly 200 crab sculptures there.

The sculptures, left unguarded and out in the open, were not completely safe, Friedman said. A few sculptures had been tipped over and split open at the seam but were repaired.

Rachel Dickerson, a manager of public art in Washington and who worked on the panda project there, said one panda was stolen and later recovered, and vandalism occurred on other statues.

“Ears were broken off of them,” she said. “There were some markings, but since we had a polyurethane coating, it was easily wiped off.”

Flanagan acknowledged Testudo is not free of similar threats.

Contact reporter Kevin Litten at litten@dbk.umd.edu.

Fifty of these full size Testudo will be constructed by Weitzman Studios, Inc. over the next few months.