The University of Maryland is a school proud of its diversity.

From admissions presentations to speeches given across the country, officials are quick to note the colorful mosaic that makes up the university’s student population, academic offerings and research efforts.

But those aren’t the only aspects of the school that are diverse — the buildings where the community lives, eats, works and studies are just as individualistic.

There’s Morrill Hall, with its sloped mansard roof, a relic from the university’s early days as an agricultural college in the second half of the 19th century. There’s Carroll Hall, a dorm built to house female students in the 1950’s. There’s Knight Hall, the university’s first LEED certified building.

Maybe it’s the architecture or maybe it’s a lack of air conditioning — these buildings draw strong responses to the students and faculty who walk through their doors each day. Here, we explore the places where we live and learn, for better or for worse.

‘NIGHT AND DAY’

A one-way street and a sidewalk separate Easton Hall from Oakland Hall, but inside, the differences between the dorms couldn’t be more drastic.

Walking into Oakland, students pass through large glass doors into a brightly lit lobby with high ceilings and open lounge areas. Residents live in air-conditioned suite-style rooms, which are connected by a bathroom. Laundry facilities and two study lounges are located on each floor. Completed in 2011, Oakland became the first new dorm almost 30 years.

“It has a lot of advantages to it,” said Mike Glowacki, assistant to the resident life director. “It was designed with today’s students in mind.”

But just a few feet away in Easton, students squeeze into forced triples. Built in 1965, Easton looks and feels every bit as old as it is, some residents said. There is air conditioning, unlike some other dorms on the campus, but older bathrooms, tiled floors, cinder block walls and narrow hallways give Easton a drab feeling, some students said.

“The difference between the two halls is night and day,” said sophomore geographical sciences major Ryan Latgis, who lived in Easton in the spring before moving to Oakland this fall.

It’s a similar situation on South Campus, where pipes line the walls and ceilings of some dorm rooms. In Carroll Hall, the only lounge is located in the basement, and there’s a small study area by the dorm’s entrance.

Students often bunk their beds in Carroll and Wicomico halls — the only way to fit all the furniture in the room, said Rashel Maikhor, a freshman communication major. Maikhor ultimately put her dresser in another student’s corner room because it wouldn’t fit in hers.

And in Carroll, the heat is unbearable for some students. Maya Lieber, a sophomore civil engineering major, was disappointed to find the building had no air conditioning. She found ways to keep cool by purchasing multiple fans and only going back to her room when she needed to sleep.

Maya Lieber

“If I am kept up until 3:45 in the morning because it’s so hot in my room, there is definitely a problem,” said Eitan Lupovitch, a freshman biology major.

Glowacki said the Department of Resident Life is in the process of completing a housing strategic plan, which it expects to finish by the end of the semester.

“Even some of the older buildings that haven’t been renovated recently — they’re in good shape,” Glowacki said. “What we’ve got to do make decisions about what the future of our housing program will be.”

Though some people might complain that buildings such as Wicomico, Caroline and Carroll are smaller and not air conditioned, Glowacki said returning students often choose those buildings because of their location near the center of campus.

“I found the positives and I enjoy it fine,” Lieber said. “I like the location of the dorm, but I find it crazy that I’m paying the same as a student who gets air conditioning.”

Despite some complaints about Easton’s living conditions, Latgis said he found a silver lining in his experience.

“The camaraderie is much better [in Easton],” Latgis said.

And as ambivalent as students feel about living in older buildings, the more historical academic buildings also have their supporters and naysayers.

Economics professor Naveen Sarna said working in Morrill Hall, the oldest academic building on campus and the host of his office, evokes a sense of pride in the school’s long history.

But Sean Combs, a senior sociology major who also works in Morrill, has a different take on the experience.

Combs previously worked in Tydings Hall, moving to Morrill with the behavioral and social sciences college offices while their Tydings space underwent construction. Though neither building possessed the grandeur of the more recently constructed buildings such as Van Munching and Knight halls, drawing comparisons has been inevitable.

“You don’t mind the old buildings until you’ve been to the nice new buildings and seen all the features,” Combs said.

‘IT’S NOT A CHOICE’

But despite the opinions of students, the school is limited in its ability to restore and equalize the campus living, eating and learning spaces. Rather, inequality in facilities is an unfortunate byproduct of being a large school.

And, facilities management officials said, the older buildings that draw the ire of students are not among their favorites, either.

“The building systems and building envelope are not up to energy standards,” said Bill Olen, capital projects director.

Because they aren’t as efficient as newer buildings, the more historic campus facilities consume more time, money and energy, Olen said, and they often need a greater number of repairs throughout the school year. And that’s a burden difficult to shoulder for facilities management officials, who have a backlog of repairs and projects.

There have been some efforts to update older buildings. Chincoteague Hall, for example, underwent extensive renovations from 2009 to 2011 to bring the hall up to code and transform it into an environmentally friendly academic building. The project cost more than $7 million.

Officials have also spent time updating the dorms. Over the past several years, officials have worked to install air conditioning in many of the North Campus high-rise dorms. The project isn’t complete yet, but Elkton Hall is the latest to receive the amenity, with air conditioning available this year.

Bill Olen

Several South Campus dorms — many of the oldest on the campus — still lack air conditioning. Wicomico, Caroline and Carroll halls, which were built in the 1950s, likely won’t see air conditioning or any major renovations soon, Olen said.

Those buildings — which are in close proximity to Prince Frederick Hall, the new dorm currently under construction — are slated to be demolished. The new dorm will have suite-style rooms and spacious lounges similar to those in Oakland Hall. The demolition hasn’t been approved yet, Olen said, which leaves the existing buildings and the students who live in them in a sort of limbo.

“Until the future is understood, we will not spend large dollars on anything but safe occupancy of the buildings,” he said. “Safety is [the] only concern right now.”

There are stark differences between academic buildings, too. Academic and residential facilities projects don’t share funding, Olen said, and academic buildings are as much, if not more so, at the mercy of available school funding.

Some university academic departments and schools have made contributions or raised funds in order to update and renovate their buildings. Private donations helped pay for Knight Hall, home of the journalism college, the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center and the Jeong H. Kim Engineering Building, which explains why some buildings receive attention and others don’t, Olen said.

“It’s not a choice,” he said. “We respond to what’s in the [approved] budget; we’re just the ones that implement it.”

In other cases, the historic value of a building hinders attempts to add amenities such as air conditioning, and often the exterior of the building must be preserved. In addition, the more dated buildings do not have elevators and therefore are not handicap accessible.

As officials prepare to transform Holzapfel Hall into Edward St. John Learning and Teaching Center, Olen said, they are consulting the Maryland Historical Trust to see what changes need to be made to keep the design plans in compliance with preservation guidelines.

DAYS OF GLORY

It’s rare to find a student who hasn’t set foot in the campus dining halls and even rarer to find one who doesn’t have an opinion on the food served.

It’s not only location that matters, but what is at that location. While Dining Services officials say the North and South Campus dining halls are equal in food and service quality, students say the dining experience is markedly different, leaving some lusting for the greener grass on the other side of the campus.

“People just get tired of their own diner eventually,” said Jonathan Hao, a sophomore computer science major who lives on South Campus.

The North Campus Diner seems to run faster, Hao said, but he prefers the South Campus Dining Hall because he can see his food being made.

The North and South Campus dining halls were both once on the cutting edge of design and food service. After a renovation in the 1980s, the North Campus Dining hall, then known as the Ellicott Diner, received national recognition from food service publications for its innovative style evoking a traditional ’50s diner, while the South Campus Dining Hall was crafted to make students feel like they were eating in an Italian kitchen.

But gone are the days of glory — the look and feel of the South Campus Dining Hall is still stuck in 1989, the year of its last renovation, and it leaves both the atmosphere and student appetites hungering for more, said Richard Stevens Jr., a junior sociology major.

“With the diners, sometimes the atmosphere can feel a bit drab, and that can definitely affect your appetite,” he said.

But even back in the day, when the halls were new, students were still dissatisfied with the food provided and the overall experience. One student told Diamondback reporters in 1989 the fresh design didn’t make up for the watery soda, and another said the renovated interior would be almost a disservice to the dining experience, as it would draw long, frustrating lines.

Richard Stevens Jr.

Today, the newest dining hall complicates the student dining experience: 251 North, the all-you-can-eat dining hall, which opened in September 2011. It features gourmet food and a more open, social dining experience, said Dining Services spokesman Bart Hipple.

It’s also become a source of tension.

Once a week, North Campus residents get to experience 251 North. The space is open and cheerful, and for some students, the pastas, pizzas, burgers and more are the highlight of the week.

“Expectations are a little higher, so you feel like the food tastes a bit better [at 251 North],” Stevens said.

The dining plan for South Campus residents, however, allows for just four meals at 251 North per semester.

“Four [times a semester] is almost enough, but not quite,” Hao said. “Maybe once every two weeks would be good.”

The granite counter tops and gourmet food at 251 are undoubtedly welcoming and impressive, Hipple said, but what he notes about serving students is they only see the present and future of the diners, because they were not there to experience the past.

“As we build things, we learn,” Hipple said. Future renovations are in the plans, but when these will occur has yet to be determined.

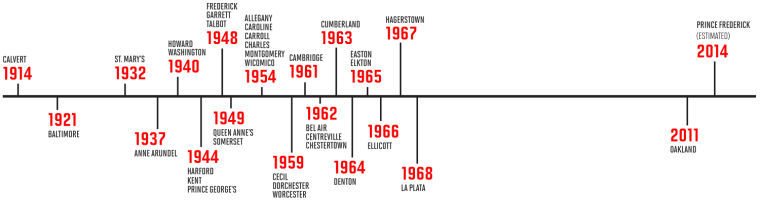

Campus dorms

Senior staff writers Laura Blasey, Jenny Hottle and Lauren Kirkwood; staff writers Matt Bylis, Holly Cuozzo, Madeleine List and Dustin Levy; and photo editor James Levin contributed to this report.

Carroll, Caroline, Wicomico, Montgomery, Allegany and Charles halls all opened in 1954.

This timeline shows when the university constructed dorms. Students are scheduled to begin moving into Prince Frederick Hall, the university’s newest dorm, in fall 2014.