D’Qwell Jackson likes to spend most of his free time lounging on the couch with his girlfriend, watching movie rentals. On Sunday nights, she usually makes him watch Desperate Housewives instead of football.

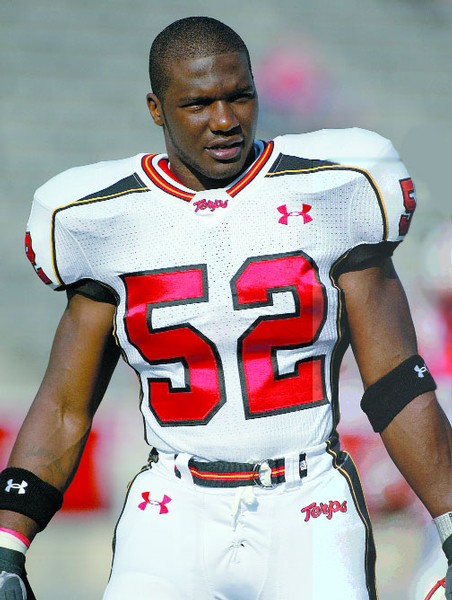

But when the switch is turned on, the Terrapin linebacker perks up, begins yelling at his players and demands victory. At this point, he is no longer the quiet, laid-back young man his friends and family know – he’s transformed into what his uncle calls the “Qwell-a-monster.”

In this case it’s just a typical video game football match-up between Jackson and one of his South Campus Commons roommates, but that’s no reason for his intensity to subside.

“Oh, it’s the same,” he said. “It’s football, so it’s competition. You get those juices flowing.”

The senior says he likes to control a linebacker at all times when playing college or professional football simulations, but on Saturdays, he seems to have an impact on every player on the field.

For Jackson’s teammates, it’s hard to explicitly say why they elected him a captain as a junior and why all but two of them voted him to the same status this season. It just seemed so simple.

“He’s a leader,” fellow captain Jo Jo Walker says.

“He’s the most reliable guy we have,” defensive tackle Conrad Bolston adds. “I wouldn’t understand anybody not voting for him.”

Backup middle linebacker Wesley Jefferson said he even holds Jackson to the same standard as he does the Terp coaches.

But Jackson only visibly demands attention when he’s between the lines. Once he steps off the practice field and is approached by reporters, his voice lowers to a whisper and his words would hardly seem worthy of sparking a locker room full of players to a frenzy.

“It’s not what he says – he’s a quiet guy – it’s more what he does on the field,” Bolston says. “You can see the effort he plays with and you can see his passion for the game. Guys are just drawn to that. You’ve got to have that respect for people to listen to you to be a leader.”

And that respect can be traced back to the time when Jackson began learning the game of football in his uncle’s backyard at the age of six.

Jackson was primarily raised by his uncle, Charles Dixon, and his grandmother. His parents are a subject he doesn’t like to discuss.

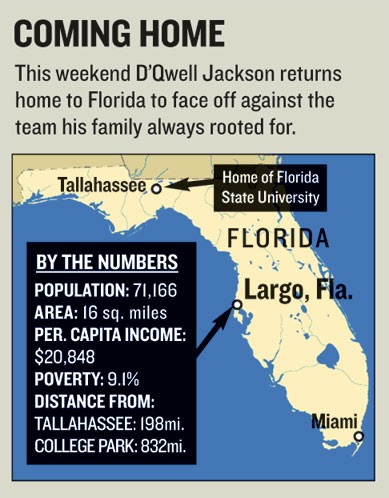

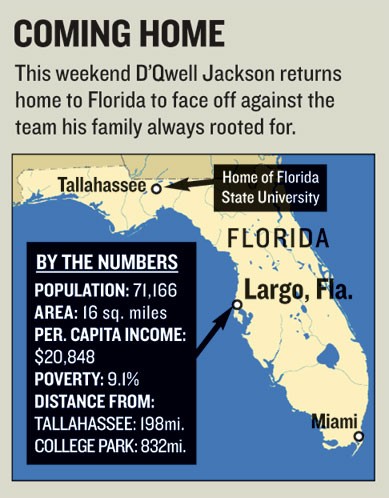

Dixon admits the family grew up in a poor community in Largo, Fla., and a lifestyle plagued by guns and drugs lurked just around the corner. Life on the streets tempted Dixon, and after spending four years in the Marines as a young adult, he wasn’t going to allow Jackson to encounter the same obstacles.

So the former high school football star began training the specimen, which has become D’Qwell Jackson, for two hours every day. Tomorrow, the monster returns to his home state for a final game against the Florida State team he followed as a youngster.

The reluctant leader

It became clear Jackson had been drawn to football when he went in the yard and practiced by himself after Dixon’s initial lessons.

Jackson’s interception of Virginia Tech quarterback Marcus Vick’s pass Oct. 20 seems like a routine task compared to some of the drills Dixon put the linebacker-in-training through.

When Jackson was just seven years old, Dixon said he would stand 10 yards away and fire a football at the youngster’s chest. There were only two options – catch it or crumble to the ground in pain.

“He taught me how to be a man,” Jackson says. “He taught me everything I need to know about football.”

And in Dixon’s mind, that was the ticket out of a less-than-ideal environment.

“I told him football would take him everywhere he’d need to go,” the 38-year-old says.

Dixon also realized ingraining Jackson with a leadership role would help keep the adolescent away from the trouble he encountered.

“If you’re a leader, you do not want to have people seeing you do things that are stupid,” Dixon says. “That’s what I learned when I became a leader.”

Dixon said Jackson has been motivating his teammates since youth football, but the vocal aspect wasn’t always present.

Jackson transferred from Largo High School to Seminole High school before his sophomore year, and after a disappointing loss early that season, Jackson remained on the field to wallow in disappointment. He complained to Dixon that his teammates seemed like they “didn’t want to play.”

At that point, Dixon – a much more vocal person by nature – taught Jackson sometimes it wouldn’t be enough to just go out and play at the highest level. It was going to take more than just Jackson’s actions to inspire the team.

With that in mind, Jackson led Seminole to a 23-4 record during his last two years, including an undefeated regular season in 2000.

When Jackson felt the Terps weren’t playing up to their potential after three games this season, he let loose in the locker room Sept. 24 at Wake Forest.

Jackson broke out of his quiet pregame focus and began a boisterous rant that culminated in his leaving a fist-sized dent in a white board. Of course, the defense couldn’t help but elevate its play, forcing four fumbles in a 22-12 win that afternoon.

On the sidelines, Jackson is a fixture standing before his seated teammates with a finger pointed in their faces. That’s the role he has developed, but when it comes to the silent leadership, Jackson is a natural.

He and Walker initially struck up a friendship as freshmen, and watching Jackson has helped the senior wide receiver emerge out of his role as a player who admitted to not playing his hardest at times last season into an elected team captain.

“He taught me to always give 100 percent,” said Walker, who is also one of Jackson’s roommates. “I would look at him during winter and summer workouts. At the end of every workout we’d do up-downs. We would do 35 and he would do 36.

“That’s the approach I took this summer, that you’ve got to do the extra one. Stand in the weight room extra, watching extra film. I’m just following a great leader, trying to be a great leader.”

Even opponents feel Jackson is good enough to inspire greatness within them.

Clemson coach Tommy Bowden said he challenged junior linebacker Anthony Waters to outplay Jackson when they visited College Park earlier this season.

“Waters had his best game I think when he tried to compete with No. 52,” Bowden said. “After that, [Waters] has led our team in tackles every game. [Jackson] is good, and he has elevated our level of play. He’s the best we’ve seen.”

The one that got away

Of course it would seem more likely for a high-caliber player from Florida – who went to Seminole High School nonetheless – to stay in the south. He looked into going to school at Florida State, which was a few hours from his home and the team his uncle supported.

There’s no question Jackson had the credentials. Once in high school, an announcer quipped the only thing Jackson hadn’t done in his career was make a tackle on his own punt.

“Guess what he did,” Dixon said.

But Jackson wasn’t the biggest player then – and still isn’t at 6-foot-1-inches, 231 pounds.

When he’s on the field, Jackson creates the aura of a beast similar to former Terp linebacker E.J. Henderson. But when the pads come off, it’s surprising to see how modest his frame appears.

And that alone separated him from other linebacker recruits.

The Seminoles never showed a great deal of interest in Jackson – who was also courted by Florida, Louisiana State and N.C. State – and he was not offered a scholarship.

“That happens a lot, and especially down here in Florida where there are so many players,” Florida State coach Bobby Bowden says. “You can only take so many. Maybe you’re only looking for two linebackers and maybe you think you see some others that are bigger and you offer them [scholarships].”

Bowden admits he doesn’t recall Jackson’s visit to Florida State, but he certainly remembers the 58-yard interception return for a touchdown Jackson had in Tallahassee two years ago and many of the team-high 11 tackles in the Terps’ 20-17 win last year.

The Seminoles have two linebackers that join Jackson on the Butkus Award semi-finalist list, but Bowden still feels a bit haunted by his decision not to offer him a scholarship.

“You find out you’ve offered the wrong one,” Bowden says. “He’s one of those you realize you made a mistake on.”

For Jackson, though, not receiving interest from Florida State was hardly a heartbreaking situation.

Jackson and his family were excited at the possibility of him earning a degree, and he is expected to become the first of his grandparents’ 10 grandchildren to do so.

“It wasn’t really a big deal,” Jackson says. “I probably would have came to Maryland anyway. I really just liked it here.”

When he returns tomorrow it will be a big deal. Jackson expects to have about 30 friends and family from home at the game, including his uncle and mother.

Dixon says Largo used to stop in its tracks when Jackson played. Dixon admits he’s “still garnet and gold all the way,” except when Jackson faces Florida State. And in this case, he wants his nephew to hold nothing back.

“I want it messy,” Dixon said. “I want blood and guts.”

No reversal of fortune

Along with being named one of 10 semifinalists for the Butkus Award – given to the best linebacker in the country – Jackson was named one of 14 quarterfinalists for the Lott Trophy on Wednesday. Named after Southern California and San Francisco 49ers star, Ronnie Lott, that award recognizes the defensive player with the largest impact on and off the field.

There’s no doubt of his merit for the in-game facet, but Jackson’s extracurricular activities often go unnoticed. He mentors elementary school students and was also instrumental in the Terps’ decision to donate their per diem from two games earlier this season to Hurricane Katrina relief efforts.

The Terps are also pushing for the nation’s top tackler (13.83 stops per game) to be considered for All-American status. He is featured prominently on the team’s media guide and on notebooks the Athletics Department distributed to reporters on media day.

Perhaps some of those trophies will one day wind up on a mantle, only it won’t sit under the “Impossible is Nothing” Muhammed Ali poster in Jackson’s room.

Jackson doesn’t like to flaunt his accolades, so all of the hardware winds up in the bedroom of his girlfriend, Amira Baker, who keeps “a D’Qwell Jackson shrine.”

“Football doesn’t define him as a person,” Baker says. “It’s just something he happens to be great at.”

Baker and Jackson grew up in the same town, and by coincidence Baker goes to dental school at Howard University. Baker said she never would have expected to date Jackson in high school because he seemed so quiet all the time.

But she says after spending a significant portion of time with Jackson, he opens up his personality.

Baker often finds herself in stitches of laughter when she watches Jackson laying punishing hits from the sideline.

“It’s like a different person or element,” she says. “Sometimes I’m like ‘Why do you have to hit them so hard?’ But it’s exciting to watch.”

After spending a few years with him, Baker has as close to full access to Jackson as anyone, but she says she isn’t allowed to talk to him before games. Baker also gets flack for being in the room when Jackson gets engaged in a video game battle with his buddies.

Perhaps the only difference with those virtual showdowns is Jackson doesn’t vomit before playing, as he has done prior to each game since he played youth football, Dixon said.

The butterflies may get to Jackson before kickoff, but they don’t escape his uncle during the games. Dixon says it is stressful at times to watch, because he realizes a major injury is the only thing that will prevent Jackson from an NFL career.

For that reason, Dixon can’t wait until the season ends – plus he says he is looking forward to being able to remove the “Terps” decals from his truck and return to rooting for the Seminoles.

According to some experts, Jackson could have been selected in the first round of last year’s NFL Draft, but he decided to come back and try to finish his career on a winning note.

Wrist surgery wasn’t necessary before the season, but coach Ralph Friedgen told him to have the operation during the spring so it wouldn’t affect his draft status after the year.

“I just wish the best for D’Qwell, because what he’s given us over the four years he’s been here is really remarkable,” Friedgen said. “D’Qwell Jackson is a heck of a football player, but he’s a better person and leader than he is a football player, and that’s a large statement. We’re a better program because D’Qwell came to school here.”

And the opportunity with the Terps is something Jackson, his family and his friends have cherished.

“I don’t think that anything else gets him that excited. Just being on that football field,” Baker said. “That’s his domain.”

In the weeks leading up to Jackson’s scheduled arrival at the campus before his freshman year, his excitement continued to mount. Jackson was so thrilled to be joining the Terps that Dixon took him up to the campus early for workouts.

On the way, Dixon remembers Jackson talking about Henderson, the Terps’ two-time All-American middle linebacker, and the legacy he could follow.

But that went against all of the leadership lessons Dixon taught his nephew.

“Enough about E.J. Henderson,” Dixon said he told Jackson. “You make them say ‘D’Qwell Jackson.'”

Whether you’re in Largo, Tallahassee or College Park, there’s a good chance he’s someone they’ll be talking about – this weekend and for some time.

Contact reporter David Selig at dseligdbk@gmail.com.