[Editor’s Note: Part 3 in a 4-part series addressing the integration and history of blacks at the university]

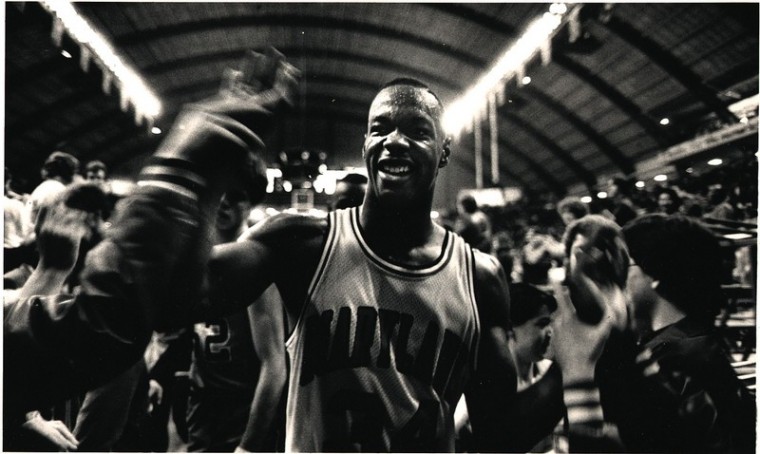

Len Bias strode to the podium, a beaming 22-year-old dressed in a white suit, white shirt and black tie who had averaged more than 20 points a game for the Terrapin men’s basketball team in the 1986 season. He had just been selected second overall by the best team in basketball —the Boston Celtics, where he’d play alongside legend Larry Bird — and was destined for fame and fortune.

Less than two days later he would drop dead from a cocaine-induced heart attack suffered just hours after the greatest moment of his life.

When the dust cleared, legendary basketball coach Lefty Driesell and his successor Bob Wade, along with athletics director Dick Dull, were ousted amid scandals. There were few people left standing.

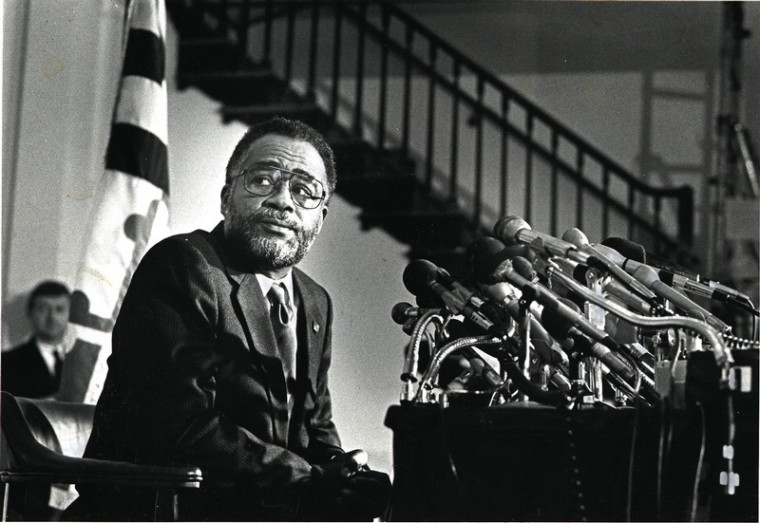

But one of the central figures criticized in the ordeal would leave on his own terms. Almost two years later, the university’s first black president, John B. Slaughter, announced he was leaving the university for Occidental College — a small, almost all-white college outside of Los Angeles.

Though Slaughter’s term is largely remembered for the Bias controversy, it was also an important step in the university’s racial progression — after denying blacks admission to the university for more than 100 years, the school was not only seeing an increase in undergraduate minority enrollment, but it had become one of the first historically white universities to be headed by a black leader.

Slaughter’s successor, Brit Kirwan, would continue to push for increased diversity, but a lawsuit questioning the constitutionality of a scholarship for black students would lead officials to make startling revelations about the university’s past shortcomings.

‘SACK SLAUGHTER’

John Brooks Slaughter was a 48-year-old Kansas-born engineer with two decades of research experience when the nation’s seventh-largest public university came calling. Appointed by President Jimmy Carter as the first black leader of the National Science Foundation in Washington, the soft-spoken, low-profile Slaughter left two years into his six-year term to take over this university — a black academic leading a sports-heavy campus with just a 7 percent black undergraduate class.

“He was the first black to head a traditionally white university — a big deal,” said George Callcott, a university historian and history professor emeritus. “And the interesting thing is how Slaughter was accepted. Nobody at College Park thought this was unusual … They were praised for reaching out to this very able educator.”

Slaughter quickly reinforced the praise with four productive years. The academic standards were improving, and he was named head of the now-disbanded NCAA Presidents Commission. He continued the improved minority recruiting of his predecessors, Charles Bishop and Robert Gluckstern.

Then all hell broke lose.

Bias flew in with his father from New York — the site of the NBA draft — and went to his family home in Landover, according to The Washington Post. He arrived in College Park around midnight, where he ate crabs in his Washington Hall dorm until 2 a.m.

He drove off alone, was seen at an off-campus gathering and returned to his dorm about 3 a.m. He collapsed after 6 a.m. while talking to a teammate.

Two days later, Bias was dead.

The university was immediately under a national spotlight. A series of oversights — including players using drugs and flunking out — were uncovered, and the beloved Driesell stepped down. There were calls for Slaughter to resign, something he agreed to do if he had to.

“Here was one of the few black executive officers of a major university campus about to bite the dust, it seemed, because he had not kept a close enough eye on his sports program,” lamented Post columnist Courtland Milloy.

Just two days later, Slaughter hired Bob Wade — a wildly successful high school coach with no college experience — to replace Driesell. Wade, who is black, was the only candidate interviewed, and the alumni boosters were not pleased. In short, he was destined for failure.

Slaughter received racist hate mail daily. At a men’s football game, a group hired a plane to fly a banner over Byrd Stadium. “Sack Slaughter,” it read.

“There was resistance to having a black coach in the first place, but the way he did it gave them further ammunition,” said Cordell Black, associate provost for equity and diversity. “Racism wasn’t dead,” added Callcott.

Athletics were overshadowing academics. At a time when black enrollment was dropping nationwide, the university increased its black enrollment by 17 percent. The number of faculty members rose by 170, 12 of whom were black. The average SAT score increased from 982 to 1,032, and more money was being directed toward graduate fellowships and faculty research programs.

But the timing was right for his departure — both for him and for the university, said William Sedlacek, an assistant director of the Counseling Center who was close to Slaughter.

“He was a quiet, composed leader. Quiet, dignified and very smart guy who knew what he wanted to do,” said Sedlacek, who has advocated racial issues at the university since 1969. “Slaughter was cool — he waited ’til things died down a bit and then left. That was probably best for all concerned.”

PROGRAM QUESTIONED

Current chancellor Kirwan — who served as provost under Slaughter — had enough on his plate when he became president at the close of the 1980s. Then-Gov. William Donald Schaefer and the General Assembly launched a bold vision to make the university a top-tier research institution in 1988, but in just a few years, they slashed the university budget by 18 percent.

Then in 1990, a student from Baltimore County named Daniel Podberesky enrolled at the university as a freshman and began applying for scholarships. He met the requirements of the Benjamin Banneker Scholarship Program except for one thing — he wasn’t black.

The Banneker scholarship was introduced in 1979 by then-Chancellor Robert Gluckstern after the government threatened to withdraw $65 million from Maryland state colleges for allegedly failing to produce adequate desegregation plans. It was designed for high-achieving black students, giving them a four-year scholarship that included tuition, room and board, mandatory fees and book allowances.

Born in Louisville, Ky., Kirwan grew up in the South and attended segregated schools. From his first day as president, Kirwan listed diversity among his top priorities.

“I can remember from my earliest recollections feeling how unjust segregation was,” he said Tuesday. “I grew up with very strong emotional feelings about the inequities in our society created by race and prejudice.”

The courtroom battle for Podberesky v. Kirwan was a strange reversal. To prove the program was necessary, the university and state argued the university was so hostile toward blacks that such a program needed to exist.

On the other side of the room, the plaintiffs told the judge the university was doing an admirable job in graduating black students and didn’t need race-exclusive scholarships.

“It was hard,” said Susan Bayly, general counsel for the university. “Here the university was trying to desegregate and attract high-achieving minorities, and we say, ‘This is a terrible place to come, it’s got a hostile atmosphere, an underrepresentation of African Americans, they don’t stay here and they don’t graduate.’”

“Some said you’re going to cause yourself harm, you’ll have to admit to your failings,” Kirwan said. “But it just seemed to me that that was the honest thing to do, because we were far from where we thought we should be.”

‘CHILLY CLIMATE’

Just a few years earlier, then-Special Assistant to the President Ray Gillian made the same conclusions in a 1989 report to the president called “Access is not Enough.” In it, Gillian, now associate provost and director of the Office of Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action Programs at Johns Hopkins University, said he sought to explain to the administration the “chilly climate for blacks” he saw on the campus.

“I was not surprised, and that was part of the intent of the report,” said Gillian when contacted recently. “I think initially people were sort of shocked and didn’t want to accept that was the experience.”

“Tensions are running high between black students and white students,” he observed in the report. “Black students are getting tired of racial slurs in the hallways and hollering of racial slurs out of windows.” Black students believed they had to prove they were in college to study, and were afraid to speak up in class “so as not to appear arrogant.”

While the university was ranked among the top three public research universities or its diversity in terms of black undergraduate and graduate enrollments, Gillian believed that was more others’ shortcoming than praise of the university.

The university compiled a similar report to defend Banneker, calling the university’s system “at best neglectful, at worst hostile.”

The report said the university had a reputation as “all-white:” “too little changed from the days of segregation, and one that can still present an unwelcoming environment for African Americans. … Past discrimination has resulted in attitudes among some members of the campus community that adversely affect recruitment, retention and graduation of African American students. This is unacceptable.”

The Banneker program helped to alleviate these problems, Kirwan said.

“When the best student in a high school came here, it sort of sent a signal that it’s OK to go to the University of Maryland,” said Kirwan, who participated in a campus vigil supporting the program.

But attorney Richard A. Samp, chief counsel for the Washington Legal Foundation — a conservative public interest law firm representing Podberesky — said it came at the expense of white students.

“The university is now trying to discriminate in favor of blacks,” he told The Washington Post in 1993, saying blacks benefited from the hundreds of programs favoring them. “It doesn’t matter what kind of discrimination existed in the past. What matters is what exists now.”

BEGINNING OF THE END

The university won the Banneker case twice in district court, but lost both appeals in the circuit court. A three-judge panel unanimously acknowledged racism existed on the campus but said the university had failed to tailor the program to correct past discrimination. A request to have the Supreme Court decide was shot down.

It was the first program of its kind to be declared unconstitutional. But while the university could not use race-exclusive scholarships, race could still be a factor.

“When the rest of the country saw what the university went through and how difficult it was going to be to justify a race-exclusive scholarship, the rest of the country began to rethink race-exclusive programs,” Bayly said. “This was sort of the beginning of the end of affirmative action with respect to race-exclusive programs.

“It was a terrible time, a terrible blow for the school, but the silver lining was … while we couldn’t use race as an exclusive factor in awarding or admitting students, we could use it as one of many factors,” Bayly said.

The university combined the Banneker scholarship with the Francis Scott Key scholarship into the Robert L. Gluckstern Banneker/Key scholarship and opened it to all races.

While it wasn’t clear at the time whether it would hold up, the university adopted the rationale of a 1978 Supreme Court ruling — the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, which recognized diversity as a compelling justification for race-sensitive — but not race-exclusive — programs.

Officials would hold their breath as these policies were challenged at the University of Michigan, but today, the university has one of the highest number of blacks receiving bachelor’s degrees among major research institutions, and the university is routinely praised for its diversity.

Tomorrow: The final installment explores the current state of the university, with officials and students weighing in on what will define the university in the next decades.

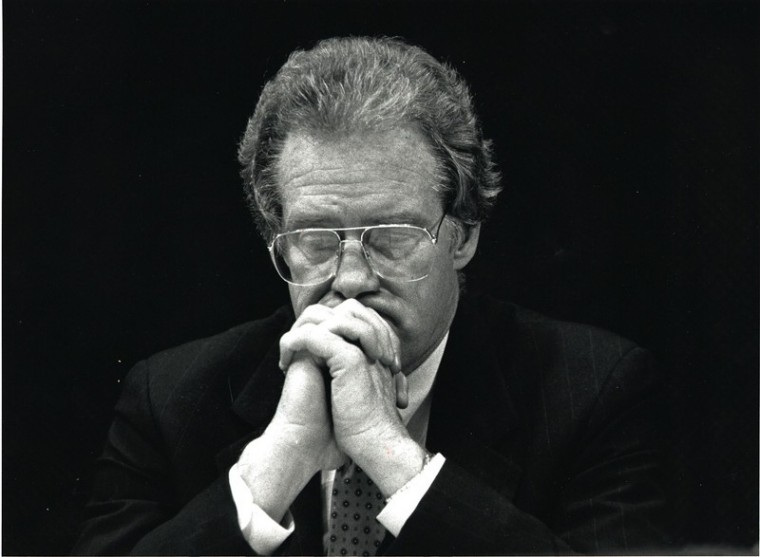

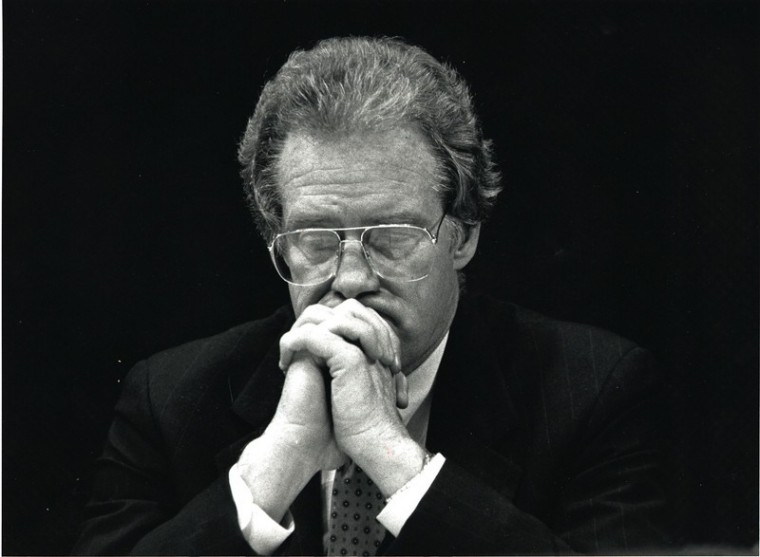

John B. Slaughter (above), the university’s first black president, overcame turmoil when the death of star basketball player Len Bias (middle) rocked the university in 1986. Slaughter’s successor and current University System of Maryland chancellor, Brit