When retired physics professor Robert Park realized he could no longer read a book, his world turned upside down.

Park, 83, had a hemorrhagic stroke in March 2013 that left him with a neurogenic language disorder called aphasia, which can affect all language abilities, including written expression and reading comprehension.

University students Zsolt Pajor-Gyulai and David Oganesyan also have speech impediments, which they said have negatively impacted the way they speak and handle anxiety.

But all three were able to find help through this university’s hearing and speech sciences department, and Park said he remains optimistic about his future.

“I’m getting better. I’m not a stopper,” he said. “I want to get back to writing and learning. I would like to get back to the person I was and write another book.”

Pajor-Gyulai, a mathematics graduate student, said he struggled with stuttering ever since he began speaking. Being an immigrant from Hungary who did not know English well made his speech and confidence issues even worse, he said.

“It did affect my life, especially through my sense of self and self-worth,” he said. “You have to go through all these hoops in your own mind, even the simple stuff that an average everyday person would never think required effort.”

Oganesyan said he did not become aware of his stuttering until he reached middle school and realized it was affecting his ability to communicate.

“My speech impediment was correlated with how badly I reacted to it,” the senior economics and finance major said. “It got to the point where I would actively not talk.”

When Pajor-Gyulai came to this university, he said, he was grateful that the university was equipped to accommodate his condition, and therapy taught him how to confront and suppress the stigma against it.

“There is nothing you can actually do with the stuttering itself,” he said. “But what you can help quickly is your attitude towards it, and you can help ease your mental struggle. You have to accept you are a person who stutters, and it’s OK.”

Margaret McLaughlin, director of the doctoral program in special education policy leadership development, said she believes creating a welcoming environment through awareness and education is valuable in helping students cope with disabilities, visible or invisible.

“I commend the campus for having a forward view on diversity,” she said. “However, we need some special focus on the students in the community.”

The major in special education is meant to prepare aspiring teachers to provide instruction to students with disabilities. Within the education school, an Understanding Plural Societies course available all students, EDSP 210: Introduction to Special Education, focuses on the stigmas and myths surrounding disability.

Although McLaughlin sees the value in providing disability education in classroom settings, she said there is a possibility of trivializing disability and creating a perception of deviance or abnormality.

“I would like to see a bigger focus on … the basic principles that talk about disability — not a separate exotic group of people,” she said.

Calvin Sweeney, coordinator for the LGBT Equity Center, said she agrees with that notion but believes it’s not enough for the university to accommodate people with disabilities.

“Being inclusive means not just making accommodations for an individual,” she said. “It means setting things up so that individual doesn’t have to ask for accommodations.”

Like Park, Sweeney has had to undertake dealing with a new disability. Shortly after moving into a new home infested with mold, she began having respiratory and fatigue issues that made it difficult for her to go to work and class.

She worked for the Office of Diversity and Inclusion at the time, and although staff were supportive of her, she realized there must be a greater emphasis on disability awareness, as there were aspects of ableism she did not understand.

This university’s “Rise Above -Isms” week last month attempted to fight issues of discrimination and prejudice in multiple facets of society.

Pajor-Gyulai said he supports the university’s efforts to address prejudice, but he believes society has a ways to go.

“You can put this under the umbrella of ‘rise against the lack of empathy,’” he said. “Don’t be oblivious to what other people are going through because of their gender, color of their skin or because they have a speech impediment. Most people don’t mean anything bad. It’s an ignorance issue.”

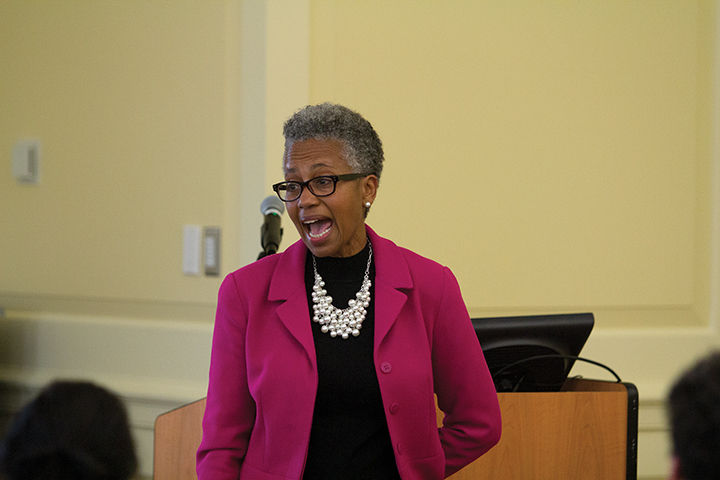

Calvin Sweeney, coordinator in the LGBT Equity Center, speaks about her diagnosis with ADHD and the support the school gave her along the way to the diagnosis. Sweeney spoke to a crowd Oct. 22 during the “Nothing About Us, Without Us” panel at McKeldin Library.

Kumea Shorter-Gooden, the chief diversity officer and associate vice president of the Office of Diversity & Inclusion, gives a speech about disabilities and diversity at this university before the “Nothing About Us, Without Us” panel Oct. 22 in McKeldin Library.